I’ve made the argument lately that I think even if bonds perform poorly from their current low yields that they could still serve a purpose as a portfolio diversifier (see here and here).

Many readers have told me that, even though they understand the arguments I’m making, it doesn’t make sense to hold bonds in their portfolio. For some, holding cash or a cash equivalent like CDs makes more sense for their fixed income exposure based on their risk tolerance. Mixing cash with stocks is a barbell portfolio strategy with a very safe short-term capital preservation asset in one bucket and much riskier assets in another.

I have no problem with this strategy if that’s what works for your situation. There’s no reason to try and implement a portfolio that you’re not comfortable with. And a stocks and cash portfolio mix does have some backing from the investment community. The late-Peter Bernstein actually made the case for a 75/25 stock/cash portfolio in an article published in the Investment Management Review in the late 1980s:

Although cash tends to have a lower expected return than bonds, we have seen that cash can hold its own against bonds 30 percent of the time or more when bond returns are positive. Cash will always win out over bonds when bond returns are negative.

The logical step, therefore, is to try a portfolio mix that offsets the lower expected return on cash by increasing the share devoted to equities. As cash has no negative returns, the volatility might not be any higher than it would be in a portfolio that includes bonds.

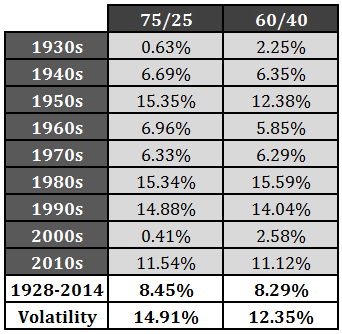

Bernstein went on to show that up to that point, a 75/25 portfolio outperformed a 60/40 portfolio more times than not. I decided to run the numbers on this portfolio and compare it to the simple 60/40 stock/bond portfolio. Here are the results, broken out by decade, for a 75/25 portfolio made up of stocks and cash and a 60/40 portfolio made up of stocks and bonds*:

The 75/25 strategy slightly outperformed the 60/40 portfolio with higher volatility, but that’s to be expected given the higher allocation to stocks. When both allocations were negative on an annual basis, the 75/25 portfolio lost an average of 12.1% while the 60/40 portfolio was down an average of 8.5%. The worst annual loss for 75/25 was -32.3% while the biggest annual drawdown for the 60/40 portfolio was -27.3%.

Larger gains and larger losses, basically what you should expect when you get rid of bonds and increase equity exposure. While the overall performance is interesting, what most investors are concerned about right now is a rising interest rate environment. You can see that the 75/25 outperformed in the 1950s and 1960s when rates rose (although the enormous bull market in stocks did much of the heavy lifting in the 50s).

Regardless of the strategy chosen, you can see that both have done fairly well over time even though there were a couple of poor performing decades. And these are both very simple portfolios. Investors can diversify globally and within each asset class as well to decrease the reliance on just the two broad assets used here.

The real benefit of diversification is to provide investors with an emotional hedge. If you’re having a difficult time handling the potential risks from rising interest rates, it could make sense to have your safe bucket in cash as opposed to bonds. If you can stomach a little more volatility for a higher yield and potential stock bear market diversifier, bonds can still provide that function even if the returns are lower than they’ve been in the past.

As with all asset allocation decisions, the numbers matter much less than your personal disposition and ability to stick with the one you decide on.

Further Reading:

The Real Risks to a 60/40 Portfolio

What’s The Worst 10 Year Return From a 50/50 Stock/Bond Portfolio?

*The 60/40 portfolio is comprised of 60% in the S&P 500 and 40% in bonds utilizing 10 year treasuries through 1975 and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index thereafter. The 75/25 portfolio is made up of 75% in the S&P 500 and 25% in short-term t-bills.

Were these numbers for a static holding through the decade, or were the holdings rebalanced through the 10-yr periods?

Good question. Annual rebalance.

In examining the Japan experience, long bond yields can go very “low”. A 60/40 mix would have done well even with yields below 1% ( slide 18 ) https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1Sn6BKRCKRU5tensBDFTkJXI3v2wRQ4M1bt8VoIM2Zmc/edit?usp=sharing

Yup, anything is possible. We’d be in trouble if we see the Japan scenario, and I think it’s a low probability event, but not out of the realm of possibilities.

Can you also include a 100% stock portfolio in your table as an additional column?

S&P 500:

1930s -0.9%

1940s 8.5%

1950s 19.5%

1960s 7.7%

1970s 5.9%

1980s 17.3%

1990s 18.0%

2000s -1.0%

2010s 15.3%

Is this really a veiled approval of Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolio service. 😉

Touche. Should I ask for a cut of their robo profits?

I’m reminded of Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio, which had both 25% cash and 25% long bonds. He conceived of it in the 1970s, when T-bills were yielding double digits.

What pains me about cash is that it’s basically a zero real return asset (maybe 1% real return during good periods, but negative real return since 2008).

This indicates the need for a third uncorrelated, not-equities, not-bonds, asset. Harry Browne proposed gold, but gold has its own issues with volatility and long bear markets.

What to do, what to do?

It’s always something…

I agree with the cash piece. It’s tough to give up on any growth with that big of a piece. One of the scenarios I could see this working is for risk averse investors that need to have 4-5 year’s worth of spending needs in cash to be able to sleep at night (retirees).

[…] An Alternative to the 60/40 Portfolio (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

Good article. The only shortcoming is that (I assume) that the bonds you are using are long duration bonds, which are much more volatile and suffer deeper losses when interest rates rise, compared to shorter duration bonds. I would be interested if you could compare your 60/40 mix to a 60/40 mix using 5-year bonds that are laddered so that they can be held to maturity and used when needed as they mature, and therefore never need to be sold at a loss. My guess is that this strategy will surpass both of your illustrations in this article, and with less volatility.

Good point. I don’t think there’s too much of a difference between the 5 and 10 year stats, but you’re correct that the 10 year would be a bit more volatile. And I agree that it’s a good idea to spread your interest rate risk for bonds in a laddered portfolio. But just remember that even though those bonds are never sold at a loss, they still have to contend with inflation.

[…] An Alternative to the 60/40 Portfolio by A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] A Wealth of Common Sense blog looks at an alternative to the widely accepted 60/40 balanced portfolio. […]

[…] about their different time horizons — the spending phase and the growth phase. This is why a 60/40 portfolio has been the standard industry benchmark for so long — it’s a balance between capital […]

great article, just what i needed to hear. id recently decided to go equities/cash portfolio .

[…] Further Reading: What’s the Worst 10 Year Return From a 50/50 Stock/Bond Portfolio? The Real Risk to a 60/40 Portfolio An Alternative to the 60/40 Portfolio […]