“The paradox of skill says that when the outcome of an activity combines skill and luck, as skill improves, luck becomes more important in shaping results.” – Michael Mauboussin

I recently wrote a post about how size is the enemy of outperformance. My main point was that extreme levels of outperformance become nearly impossible to pull off once your asset base grows large enough because you can’t be as nimble and the number of opportunities drops significantly.

It’s interesting to think about this issue of scale in terms of mutual fund assets as well. My friend Bob Seawright from Above the Market sent me the data on a number of mutual funds that have wonderful long-term track records that also have a large asset base. Here’s the list of funds:

- Fidelity Contrafund

- American Funds Income Fund of America

- American Funds Growth Fund of America

- American Funds Capital Income Builder

- Dodge & Cox International Stock

- Dodge & Cox Stock

- American Funds Investment Company of America

- American Funds Capital World Growth & Income

- American Funds Washington Mutual

These funds range in asset size from $60-$110 billion. I looked at the performance numbers and this group of funds has a nice track record of market-beating results.

Contrafund, Income Fund of America, Capital Income Builder, Dodge & Cox Stock and Capital World Growth & Income have all outperformed their benchmarks over the past 5, 10 and 15 years. Growth Fund of America and Investment Company of America outperformed over 10 and 15 years. Dodge & Cox International Stock outperformed over 5 and 10 years while American Funds Washington Mutual outperformed over the past 5 years.

The fact that the fund families of Dodge & Cox and American Funds have such consistent track records across a number of funds is impressive. The question is: Can you use the Dodge & Cox or American Fund template to choose other larger, winning funds that can outperform?

Michael Mauboussin has an interesting take on finding successful businesses in his book The Success Equation:

The most common method for teaching a manager how to thrive in business is to find successful businesses, identify the common practices of those businesses, and recommend that the manager imitate them. Perhaps the best-known book about this method is Jim Collin’s Good to Great. Collins and his team analyzed thousands of companies and isolated eleven whose performance went from good to great. They then identified the concepts that they believed caused those companies to improve – these include leadership, people, a fact-based approach, focus, discipline, and the use of technology – and suggested that other companies adopt the same sort of results. This formula is intuitive, includes some great narrative, and has sold millions of books for Collins.

The trouble is that the performance of a company always depends on both skill and luck, which means that a given strategy will succeed only part of the time. So attributing success to any strategy may be wrong simply because you’re sampling only the winners. The more important question it: How many of the companies that tried that strategy actually succeeded?

Therein lies the problem. Can you find successful active managers by choosing the ones with similar traits as the more established active funds? How many other fund companies tried similar fund structures and portfolio management techniques as Dodge & Cox or American Funds but failed to mirror their success?

These are the questions that make the investing business interesting because there’s no simple checklist to find the outperformers ahead of time. Process and culture are massively important in finding funds to invest with, but they don’t always translate into market-beating performance.

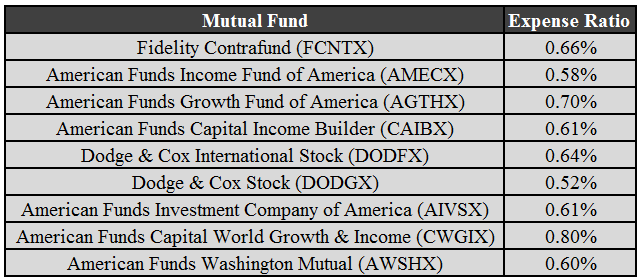

Not only do these funds have solid investment processes and the right organization culture, but they also have much lower than average fund fees:

This is where having a large asset base can actually be a huge advantage because economies of scale have allowed these funds to keep their fees small enough to lower the hurdle rate for outperformance. And the studies show that the largest predictor of fund performance is the cost of the fund.

Most of the time it’s the simplest answer that makes the most sense.

Source:

The Success Equation

Further Reading:

Index Funds and the Paradox of Skill

[…] Mutual Funds Good to Great […]

[…] Why fund fees matter. (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] Into Why Scotland Voted Against Independence (Buzzfeed) • Mutual Funds From Good to Great (A Wealth of Common Sense) • Be like Calpers: Dump your hedge funds (MarketWatch) see also CalPERS Names Ted Eliopoulous as […]

[…] Into Why Scotland Voted Against Independence (Buzzfeed) • Mutual Funds From Good to Great (A Wealth of Common Sense) • Be like Calpers: Dump your hedge funds (MarketWatch) see also CalPERS Names Ted Eliopoulous as […]

[…] (Investing Caffeine) Something’s Gotta Give (GaveKal) Mutual Funds From Good to Great (A Wealth of Common Sense) Larry Ellison’s Master Class in Being Rich and Having Fun (Business Week) How to see into […]

[…] leading factor in the success or failure of any investment is fees. In fact, the relationship between fees and […]

[…] leading factor in the success or failure of any investment is fees. In fact, the relationship between fees and […]

[…] really matter. Our second biggest problem is that we don’t care enough about costs. The leading factor in the success or failure of any investment is fees. In fact, the relationship between fees and […]

[…] reason for the underperformance is fees, which are the best indicator we have of performance success. Tactical funds on average charge an annual management fee of 1.48 […]