“Truth be told, if you keep buying high and selling low, you should stay out of the stock market, because you’re losing money. Your primary goal as an investor should be not to lose money.” – Carl Richards

In summer of 2009, I sat in on a panel discussion consisting of 3 or 4 portfolio managers that dealt with the aftermath of the financial crisis. Each PM was asked for a simple five-year forecast for the stock market. Most investors were still fairly bearish on the economy and the markets at that point even though we were slowly beginning the recovery process.

One of the portfolio managers said he thought stocks would be much higher in five years’ time and he basically got booed by the audience which was full of professional money managers and consultants. Many thought he was nuts for suggesting stocks could possibly be substantially higher after the wrecking ball of an economic and market shock we had just endured.

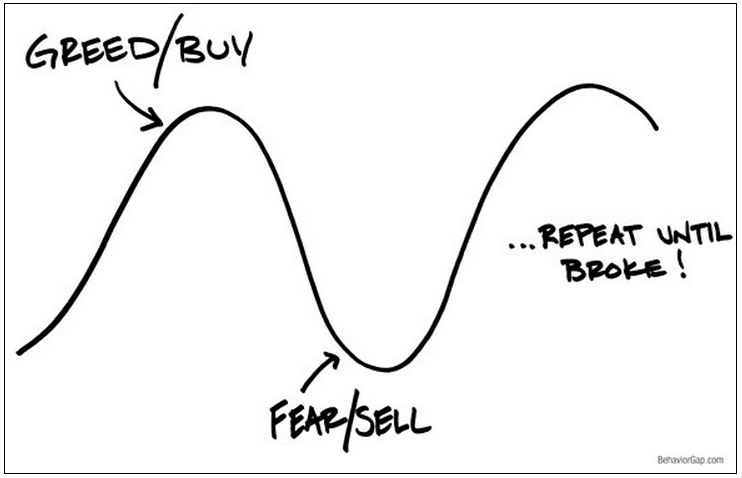

This group of professional investors was falling prey to the very same biases that affect us all. It was difficult to move past the carnage we all witnessed from the crash, yet it was a mistake to assume the bad times would last forever. My all-time favorite Behavior Gap sketch from Carl Richards sums up this dynamic nicely:

A simple line and seven words tell us a lengthy story about one of the biggest problems facing investors — behavior.

The Wikipedia list of cognitive biases currently numbers over 90 different behavioral issues that are affected by human nature. I feel that the two most important ones for investors to understand and deal with are overconfidence and loss aversion.

It may seem contradictory since these biases are on opposite ends of the spectrum. One deals with a thirst for risk while the other fears losing money. The reason both have such a powerful effect is that we have a very short memory once we start to see a string of gains or losses. It seems the current great (or terrible) times will last forever.

A study from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that this can be a generational problem based on personal experience:

Our results can explain, for example, the relatively low stock-market participation of young households in the early 1980s, following the disappointing stock-market returns in the 1970s, and the relatively high participation of young investors in the late 1990s, following the boom years in the 1990s.

This is part of the reason Millennials want nothing to do with stocks right now. The same was true for the so-called Depression Babies who dialed down their risk tolerance and became extremely frugal in the aftermath of the Great Depression.

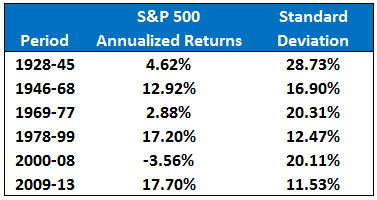

This back-and-forth between overconfidence and loss aversion can be seen in historical stock market returns over longer periods:

You can almost see the wave-like pattern in these numbers that dovetail nicely with the Behavior Gap sketch above. Highly volatile, low returning markets end in fear which leads to higher returning markets with much lower volatility followed by the eventual greed.

It can be difficult to get out of the mindset of allowing the past to guide your investment decisions because it’s much easier to extrapolate recent events out into the future than assume things will change. And once these feelings become ingrained in our thought process it’s difficult to let go and change course.

In a retrospective piece on Daniel Kahneman, Jason Zweig recalled working on past projects with the legendary behavioral expert. Zweig said he was surprised to find that Kahneman was continuously updating his ideas on most of his experiments, even if they seemed like pure gold at first glance. Kahneman was making sure he was testing everything correctly and not introducing biases into his own process.

When Zweig asked how he was able to hit the reset button on his seemingly great ideas Kahneman replied, “I have no sunk costs.”

In the business world, a sunk cost is an expense that has already been incurred with no chance of being recovered. Kahneman is saying he doesn’t allow his previous work on a project determine his thought process going forward.

The investors that are able to succeed over the long haul are the ones that are able to hit their own reset button and welcome new ideas and the possibility for cyclical changes in the markets. Letting go of your own sunk costs via your past experiences is a great way to avoid getting trapped by the cycle of fear and greed.

Sources:

Behavior Gap

Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk-Taking?

On Kahneman (Edge)

[…] Let go of your sunk costs. (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

[…] and Greed I know a lot of people out there are trapped by the cycle of fear and greed. I think it is really important that we let go but many were scared by recent events in the market. […]

[…] 13. Over-Optimism Tendency: Greed. […]

[…] Reading: Why does the cycle of fear and greed persist? A lesson in diversification and regret […]

[…] Further Reading: Why Does the Cycle of Fear and Greed Persist […]