Charley Ellis is one of my favorite communicators in the investment world. His career has intersected with a number of different investment organizations which gives him a unique perspective on how things typically work.

His book Winning the Loser’s Game is an all-timer investment book and his approach to minimizing mistakes resonated with me immediately upon reading. Ellis is a huge proponent of indexing but the firm he founded, Greenwich Associates, is a key consultant and data provider to the actively managed fund world.

Something many people might not know about Ellis is he spent a number of years on the investment committee for the Yale endowment fund, the premiere institutional investment office of the past 30 years or so. I’ve stated this before many times, but Yale’s David Swensen is the Warren Buffett of the institutional investment world.

In a piece he penned for Institutional Investor this week, Ellis broke down some of the overlooked factors that have made Swensen and Yale’s endowment so successful.

He started out discussing the fund’s mission:

The objective metrics of the Yale Model include an unusually heavy commitment to equity investments — with bonds relegated to providing only enough liquidity to meet the inherently unpredictable variations in cash requirements of a major university that has many independent inflows and outflows. Because Yale has been around for three centuries and plans to be around for at least as long into the future, the investment portfolio is unusually long-term in its composition and in the way it is evaluated.

Few nonprofits can claim to have been around for so long but most assume (hope) they’ll be in the mix in perpetuity. At least that’s the goal.

But something most nonprofits who try to copy Yale don’t have is such a well-established system of governance:

Committee members are selected by Yale’s president, the chair of the investment committee, and Swensen for their ability to add value to the governance of the management of the endowment. Then, of those chosen for the committee, some are asked to serve as trustees, a sequence that ensures first-things-first.

Committee members will long remember their responsibilities. Consistent attendance at all meetings is mandatory. At least as important is thorough preparation for active participation. Ten or more hours of reading and study before each meeting is normal. The depth and rigor of the due diligence done on managers are surely unusual and set a high standard for discussion during the quarterly meetings.

This is another one basically only a handful of other investment offices can compete with:

A significant qualitative aspect of the Yale Model is not only that manager relationships are unusually long (averaging more than a dozen years), but that many of them start at or even before the beginning of a management firm itself, when Swensen is tipped that a new organization of first-rate investors is being formed and would be well worth his consideration. Given these opportunities, Swensen has helped numerous new managers design themselves and their strategies.

Not only do they have extremely long-term relationships with their managers but in many instances, Swensen is also helping these managers get their funds off the ground in the first place (and likely getting hefty fee breaks in the process).

Why do I bring this up?

I think those endowments and foundations who are trying to implement their own Yale model are doing their beneficiaries a disservice. They’re trying to re-create lightning in a bottle. And it’s no surprise many of the nonprofits who have been able to emulate Yale’s investment office to some degree are people who worked under Swensen for years before moving on to another university or organization.

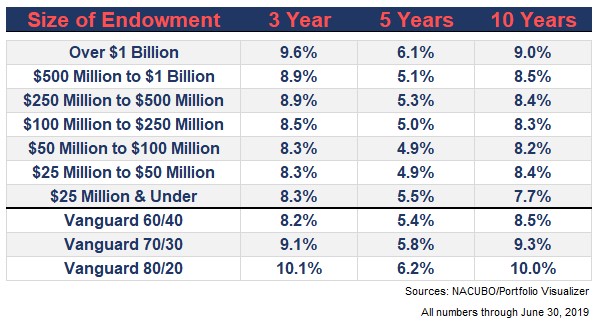

Here are the latest numbers from the TIAA/NACUBO Study of Endowments which help drive home this point:

This annual study looks at nearly 800 endowment funds to track their performance and report on such things as asset allocation. You can see a simple 3-fund Vanguard portfolio1 once again holds up relatively well against some of the biggest and best endowments in the country.

In fact, the 70/30 and 80/20 mix were both in or close to the top quartile of performance in this group (the returns were 9.5%, 5.9%, and 9.1% for 3, 5 and 10 years, respectively to be in NACUBO’s top quartile or endowments).

Every year when I write this piece I get pushback from members of the institutional world so allow me to provide some much-needed context here:

- I’m not saying every nonprofit or endowment should stop what they’re doing and immediately switch to index funds. I’m simply providing a real-world, simple, low-cost bogey for comparison purposes even if some feel this comparison is not apples-to-apples.

- The point here is not do extol the virtues of indexing but to drive home the point that complex investment structures only work under the right circumstances. You need the right people, resources, governance, and organizational culture in place. Otherwise, you’re wasting money, time, and resources that would be better spent elsewhere. This is especially true of the smaller endowments.

- There are no risk-adjusted returns presented here but even if I had the volatility numbers I’m not sure it would matter. Endowments have such a large weighting to illiquid fund structures that volatility-adjusted performance numbers are more or less useless because the prices are updated so infrequently.

- These funds have liquidity constraints in that they have annual spending targets to hit. Therefore, the Vanguard portfolios would probably be more real-world if they included a small cash piece (although you could always sell down the funds and rebalance through distributions as well).

- Politics of dealing with a board and/or committee can make it exceedingly difficult for the investment officers in many of these funds to implement the exact portfolios they would in a perfect world. This is one of the biggest challenges when investing in the institutional space.

So hopefully before I get any hate mail people take time to read this piece (Who am I kidding? I’ll definitely still get some hate mail).

My main contention here is not that every endowment should index (although many funds would surely benefit from that move) but that copying Yale is nearly impossible.

One of the biggest closed-door complaints I often heard from my endowment peers when I worked in this world was how difficult it was to institute the policies, funds, time horizons and strategies they truly wanted to because the board wouldn’t allow it.

There are many other explanations as to why some of the best and brightest allocators in the world have struggled2 (the S&P 500 outperforming everything else, a lack of volatility, crowded trades, more money in alts, etc.) but one of the biggest reasons is this: They all want to be Yale and that’s never going to happen for 99% of them.

******

One more note on the NACUBO study that I found interesting is how they reported endowment asset allocations this year.

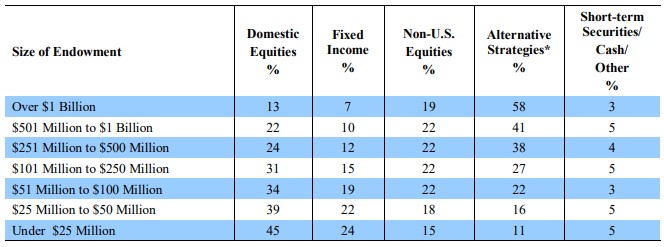

Here’s what the asset allocation breakdown looked like last year:

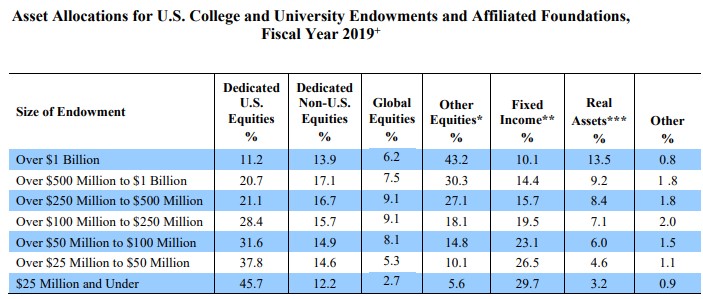

And here is this year’s version:

This is the breakdown:

*Other equities include: marketable alternatives, private equity, and venture capital.

**Fixed income includes: U.S. bonds, non-U.S. bonds, private debt, and cash and cash equivalent securities of less

than one year.

***Real assets include: TIPS, REITs, commodities/futures, publicly traded Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs),

public traded natural resource equities, private energy and mining, and private agriculture and timber.

One of the things I’ve noticed about the endowments who try to emulate the Yale model is how often they would change the labels of their asset classes to “better reflect the underlying exposures.”

Granted, this doesn’t change the structure of the portfolio but it was an easy way for these funds to change their benchmarks, thus making it easier to outperform internal bogies in most cases.

Further Reading:

Worst Practices in Institutional Asset Management

1As with previous comparisons, I used the Vanguard Total Stock, Total Bond, and Total International Funds (with the U.S.-to-international weighting set at 3-to-2 in favor of the U.S. since that’s roughly how these funds are allocated on average).

2And when I say “struggled” it’s relative to their own outstanding performance in the past where they routinely outperformed. Competition is another reason I believe these funds aren’t routinely outperforming as they did in the past.