Institutional investors are going to have a difficult time hitting their return bogeys in the years ahead.

Stock market valuations are well above long-term averages while interest rates are well below what fixed income investors are used to. This will make it exceedingly difficult for pensions to close their funding gaps or endowments and foundations to keep up with their 5% spending targets on top of inflation.

One way these funds are trying to remedy this situation is by investing heavily in private assets.

Goldman Sachs Asset Management reported 32% of insurers plan to increase their private equity investments in the next 12 months to boost their return profile. This was based on a survey of 300 insurance executives overseeing more than $10 trillion.

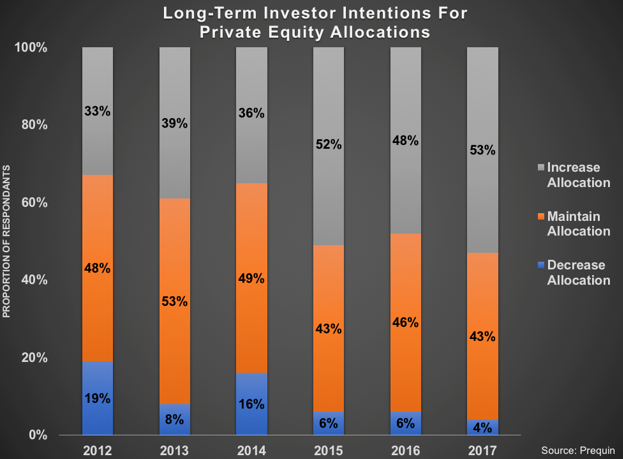

Another recent survey of over 550 large pensions, family offices, endowments, foundations and insurance companies conducted by Preqin found that these institutional funds are looking to increase returns by increasing their allocations to private equity:

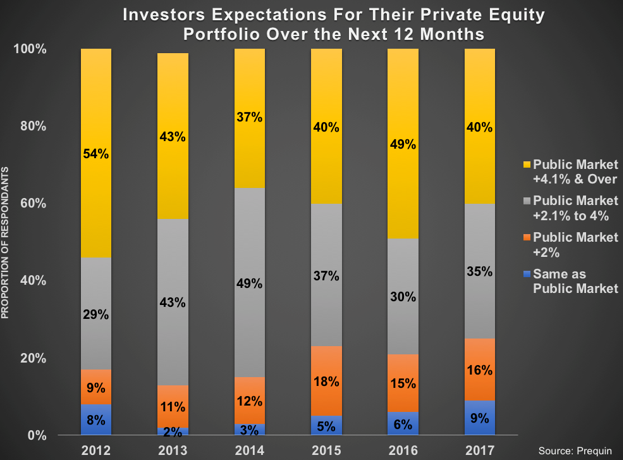

The biggest reason for this shift is the fact that so many of these investors start with the assumption that private equity will deliver higher returns than the public markets. You can see the expectations are sky high for returns in this space:

This could end up being a huge mistake for the majority of these allocators, especially the Johnny-come-lately’s who don’t understand how these assets work.

In a recent chat with Barry Ritholtz, legendary short-seller Jim Chanos shared some thoughts on the private equity landscape:

Private equity funds are different [than venture capital or public markets] because they do lever. A private equity fund should have multiple returns of the S&P if you’re using leverage. I believe they don’t.

The hope for returns that the pension funds, and endowments, and sovereign wealth funds, who just constantly assume private equity is going to earn them 10-12%, somewhat uncorrelated, just boggles my mind. It’s the ultimate correlated asset theoretically.

Investors may have been able to earn a premium in private markets in the past but things look much different now than they did for the early pioneers in the 1980s, 1990s and even early-2000s.

First of all, according to Preqin, industry assets in private equity have tripled since the end of 2006 to nearly $5 trillion. This includes the $25 billion behemoth from Apollo which is the largest buyout fund in history.

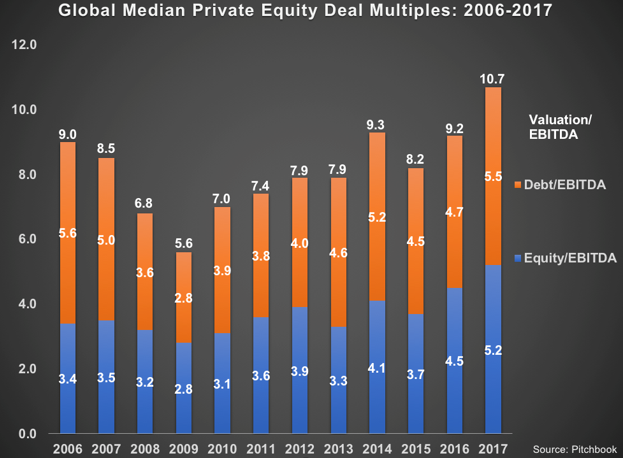

It’s estimated that private equity firms are also sitting on upwards of $1 trillion in dry powder in the form of cash commitments waiting to be invested. The sheer amount of interest and investment in this space has driven up deal multiples new heights:

Paying higher multiples for these companies puts these investors in the same situation as public market investors but with the added hurdles of higher fees, illiquid holdings, and uncertain cash flows. This isn’t great news for investors but as long as private equity firms can improve the operations and financials in these deals things could still work out.

Unfortunately, the data shows private equity funds have mainly made their money by paying lower multiples of capital, not through operational improvements to the companies they’re purchasing.

Researchers from the University of Texas performed a comprehensive study of 317 leveraged buyout deals from 1995 to 2007. They found, “little evidence of operating improvements subsequent to an LBO [leveraged buyout] on average.” What they did discover is that debt levels increased in these companies, meaning the returns to private equity investors came not from operational improvements, but from the use of leverage and rising market values.

Verdad Capital performed a similar study by looking at 390 buyout deals accounting for more than $700 billion in enterprise value. They discovered 54% of the companies saw a slowdown in revenue growth after being bought out. And 55% of private companies saw capex as a percentage of sales decrease, meaning private equity firms actually cut down long-term investments, resulting in slower growth. They also found that 70% of these deals saw private equity firms increase the debt load of the companies they bought.

It’s likely the majority of historical private equity returns came from leveraging up small businesses, not the operational prowess of the PE firms. Private equity firms could get away with excessive leverage when they were paying much lower deal multiples, but leverage could be dangerous from here when you overpay and don’t improve company financials.

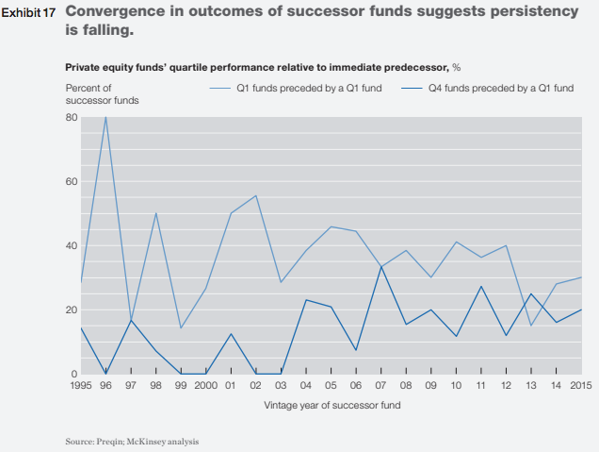

Many institutional investors tell themselves these factors don’t matter as long as they invest with the very best private equity managers (lucky for them every PE shop sells investors on the promise of being top quartile performers, something I’m pretty sure is not mathematically possible). Researchers have found that unlike actively managed mutual funds, the best private equity managers in the past have seen performance persist across different funds and market environments.

This may have been true in the past but increased competition has had an impact here as well. Analysis by McKinsey & Company found that previously a private equity firm which saw fund performance in the top quartile had a 40% chance of seeing its successor fund stay in the top quartile. That number is now closer to 25%, making it harder than ever to pick the winners across time:

Institutional investors who are investing in illiquid assets, paying high fees, levering up small companies, and locking up capital for many years in the hopes of boosting their returns may be in for a rude awakening. Nothing is guaranteed for those looking for higher expected returns.

Private equity may have offered an illiquidity premium to investors in the past, but the flood of money to this space likely means many investors are going to be disappointed in their search for higher returns in the years ahead.

Most of the endowments and foundations I talked to were shifting from large LBO funds to more niche small and mid-market funds following the financial crisis. It’s possible there are better deals in that space but the range of outcomes will be even wider and picking the winners even harder. It will be no small feat to thread that needle.

Everyone is forced to deal with the current environment and going private isn’t going to automatically save institutional investors.

There is no silver bullet.

Further Reading:

Are Private Equity Returns Overstated?