It’s much easier to come up with the reasons for a bear market after the fact so I like the idea of thinking these things through beforehand, even if it’s impossible to predict the future. Here’s a piece I wrote for Bloomberg laying out some possible scenarios that could derail this bull market.

*******

I recently appeared on Bloomberg Television’s “What’d You Miss?” with Joe Weisenthal, Scarlet Fu and Julia Chatterley, and was asked what I thought could be the catalyst for the end of this bull market in stocks, which is now the second-longest in history at eight years. That’s dangerous territory, given that investors and pundits who have been predicting a crash for a number of years now have a batting average of zero. Stocks have continued to rise in the face of mounting concerns over monetary policy, weak economic growth, geopolitical instability, concentrated gains in technology stocks and a host of other risks.

There doesn’t always need to be a legitimate reason for a pullback, but it can be helpful for investors to work through different scenarios to figure out how it could affect their portfolios. The time to prepare or adjust your expectations for market turmoil is before it occurs, not during or after the fact. I have no idea what will be the exact trigger that causes this bull market to end, but here are some possible scenarios to consider:

- The economy could go into a recession. Predicting a recession is no easier than predicting the peak in equities, but the majority of the worst stock market sell-offs throughout history have occurred around economic contractions. This would be the simplest explanation, and it’s one of the reasons investors are so concerned with indicators of economic health.

- A melt-up could turn into a meltdown. Pundits often evoke the 1987 Black Monday crash 1 when they get concerned about stock valuations getting out of control, but not enough people study what actually transpired to get to that point. From 1982 through 1986, the S&P 500 Index soared almost 150 percent and then proceeded to rise an additional 40 percent or so in the first nine months of 1987 before crashing in October. For the sake of comparison, the 1982-to-September-1987 gain of 230 percent dwarfs the 2012-to-June-2017 gain of 115 percent.

- Interest rates could rise substantially. One of the other forgotten aspects of the 1987 crash is that borrowing costs shot higher in a relatively quick fashion. The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note was 7 percent in January 1987, versus today’s paltry 2.22 percent. But yields rose all the way to 9.5 percent by October, which likely had something to do with investor nervousness surrounding the crash that year. Rising rates would initially hurt bond investors since bond prices move inversely to yields, but eventually, those higher rates would provide competition to the stock market for investor allocation preferences.

- Faster inflation. It’s something of a chicken-or-the-egg question when it comes to whether rising rates or inflation comes first since they are usually intertwined, but faster inflation is one of the biggest risks few investors discuss. In the late 1970s Warren Buffett laid out the case as to why inflation swindles the equity investor, and the reason is that stocks act like something of an infinite maturity bond investment. The 1970ssaw decent nominal gains in the stock market, but they were all but wiped out by inflation on a real basis. This same scenario is one today’s investors have little experience with, so it would come as quite a shock to the system.

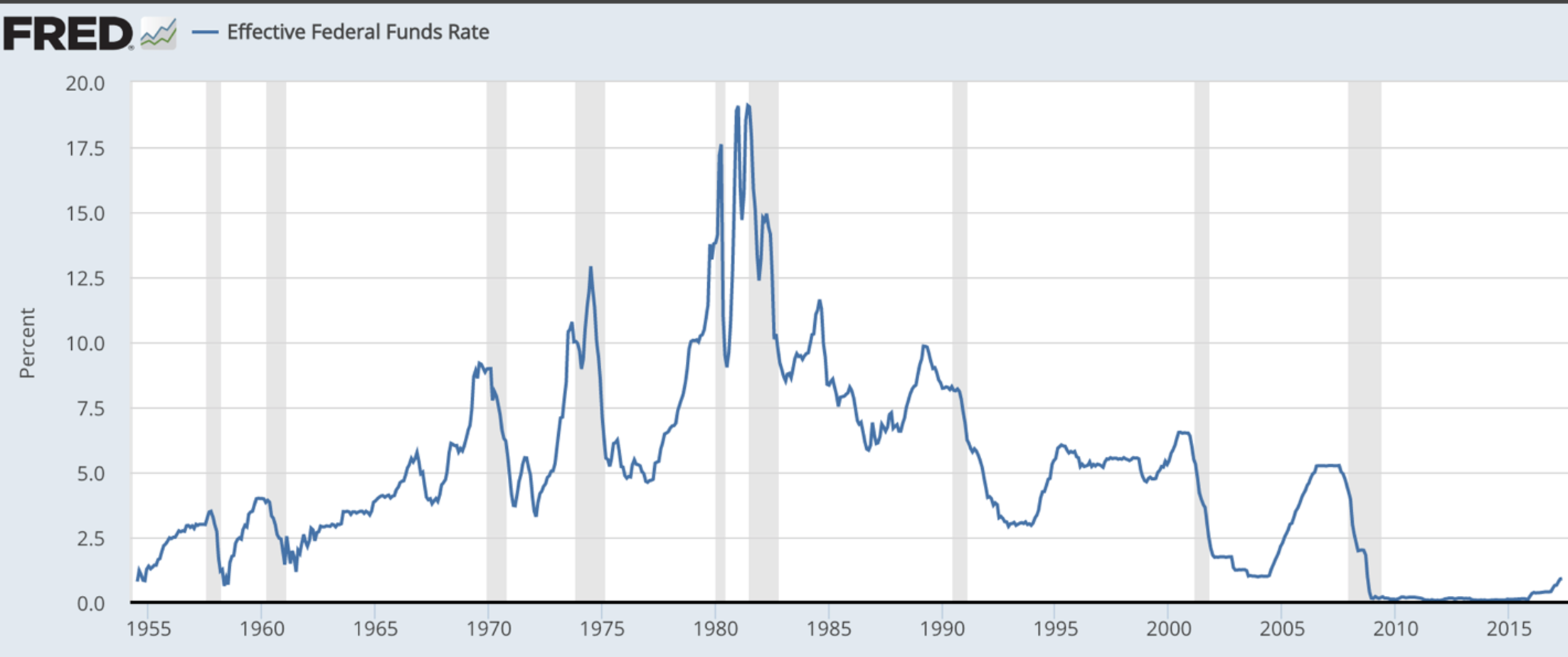

- Monetary policy could get too tight. History shows that the Federal Reserve is often part of the reason that economic expansions come to an end as monetary-policy tightening has preceded every recession since the 1950s. Each recession corresponded with a bear market in stocks.

My fellow Bloomberg Prophets contributor Tim Duy went on record last week saying we may not see the next recession until late 2019 or early 2020at the earliest. A recession is probably the highest probability event to put an end to this bull market, but it’s worth noting that stocks don’t need a recession for a meaningful correction. The S&P 500 has experienced double-digit losses one out of every five years going back to the 1930s during periods that did not see a recession.

Investors could always decide to panic for any number of reasons beyond a recession, so one way or another, it makes sense to mentally prepare for a market downturn to avoid panicking when it eventually comes.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2017. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.