There’s been a lot of talk in finance circles recently about how the economy and stock market are turning into a winner takes all venture.

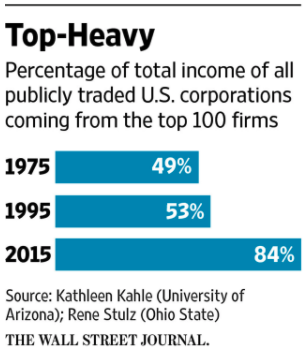

Mark Hulbert wrote a piece this week for the Wall Street Journal with a chart that sums this idea up nicely:

Not only are profits becoming more concentrated but the pool of companies is shrinking:

That means that the overwhelming majority of publicly traded corporations in the U.S. earn either modest profits or actually lose money. A related development is the drop in the number of publicly traded firms. It peaked at more than 7,500 in the late 1990s, according to Profs. Kahle and Stulz, and by 2015 stood at 3,766. Indeed, the professors wonder if we may be witnessing the coming to pass of a forecast made in 1989 by Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen, who predicted the “demise of the public corporation.”

The idea here is that fewer companies in the indexes and fewer winners leading the way will make it even harder to pick who those winners will be. It’s hard to say what, if any, the lasting impacts will be from all of this.

Maybe the 1990s was an aberration that saw far too many companies go public that never should have in the first place?

Maybe today will look like an aberration in the future and these things are simply cyclical?

Maybe regulations such as Sarbanes-Oxley have made it too onerous for smaller companies to go public?

And maybe this is how many other industries work as well.

The book Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment by Michael Smith and Rahul Telang explores how this winner takes all mentality has played out in the entertainment industry over time. A few stats from the book speak to this idea:

- In 1995, almost 85% of the global recording market was controlled by the six “majors”: BMG Entertainment, EMI, Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, Polygram, and Universal Music Group.

- In a study of movies from 2008-2010 the top 10% of movies captured 48% of all theatrical revenue, with the remaining 52 percent of revenue shared among all the movies in the bottom 90 percent.

- Harrah’s casino found that 26% of their customers generated 82% of their revenue.

- At the end of the twentieth century, six major movie studios (Disney, Fox, NBC Universal, Paramount, Sony, and Warner Brothers) controlled more than 80 percent of the market for movies and six major publishing houses (Random House, Penguin, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan) controlled almost half of the trade publishing market in the United States.

The authors explain why this was the case in the music industry:

For most of the twentieth century, the basic structure of the music industry remained the same. A group of businesses that had arisen specifically to produce and sell a single invention— the phonograph— somehow managed, over the course of several tumultuous decades, to dominate an industry that expanded to include all sorts of competing inventions and technological innovations: records of different sizes and qualities; high-quality radio, which made music widely available to consumers for the first time, and changed the nature of promotions; eight-track tapes, which made recorded music and playback machines much more portable; cassette tapes, which not only improved portability but also made unlicensed copying easy; MTV, which introduced a new channel of promotion and encouraged a different kind of consumption of music; and CDs, which replaced records and tapes with stunning rapidity.

The big companies did agree on one element of success: the ability to pay big money to sign and promote new artists. In the 1990s, the majors spent roughly $300,000 to promote and market a typical new album — money that couldn’t be recouped if the album flopped. And those costs increased in the next two decades. According to a 2014 report from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, major labels were then spending between $500,000 to $2,000,000 to “break” newly signed artists. Only 10–20 percent of such artists cover the costs — and, of course, only a few attain stardom. But those few stars make everything else possible.

I love this analogy about how music executives were like venture capitalists:

As the IFPI report put it, “it is the revenue generated by the comparatively few successful projects that enable record labels to continue to carry the risk on the investment across their rosters.” In this respect, the majors in all the creative industries operated like venture capitalists. They made a series of risky investments, fully aware that most would fail but confident that some would result in big payoffs that would more than cover the companies’ losses on less successful artists. And because of their size, they could ride out periods of bad luck that might put a smaller label out of business.

According to the book, in the 1990s the major record labels were releasing more than 130 singles and almost 100 albums per week but the radio stations would only accept 3 or 4 new songs a week for their playlists. They were basically throwing a bunch of stuff against the wall and hoping a few songs would stick.

The reason these music companies were able to control the industry for so long is because they had the scale to release such a high number of albums and incur those costs to allow the few winners to more than make up for it. But they also had little competition from new technologies, that is, until the MP3s and streaming came along. Here are some great stats from the book about how these breakthroughs impacted the entertainment industry:

By some estimates, music revenue fell by 57 percent in the decade after the launch of Napster, and DVD revenue fell by 43 percent in the five years after 2004, when BitTorrent gained popularity.

Young people’s attendance at movie theaters fell by 40 percent from 2002 to 2012. The ratings of prime-time live television shows for 18–49-year-olds fell by 50 percent from 2002 to 2011.

Companies like Amazon, Spotify, Apple, YouTube, and Netflix have completely changed the way people access their entertainment. Interestingly enough, many of these companies are now in the new winner takes all group in the stock market and economy.

But to assume that these winners will stay atop their perch forever would be madness. Some might, but more than likely a new group of winners will emerge in the future. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos even talked about how this happens in his shareholder letter which was released this week:

Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.

Bezos is doing his best to ensure Amazon stays a winner but who knows if another company won’t become the next Amazon of the future.

So while I think it’s possible the winner takes all economy could be around for a while there’s no guarantee it will last. And even if it does, it’s highly likely that tomorrow’s winners will be different from today’s.

Sources:

Investing in a ‘Winner Takes All’ Economy (WSJ)

Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment

Now here’s what I’ve been reading this week:

- One power laws and time (What I Learnt on Wall Street)

- “You need to judge us over a full cycle” (Reformed Broker)

- Just keep buying (Of Dollars and Data)

- How changing the paint color in a restaurant increased profits (Growth Lab)

- “I have no bucket list. Life is the bucket.” (Season of the Witch)

- Keep ETFs weird (Enterprising Investor)

- Investing doesn’t have to be an all or nothing game (Irrelevant Investor)

- Are expected interest rate changes priced into bond prices? (Oblivious Investor)

- Jon Hamm’s money lessons learned (Wealth Simple)

- Peter Lynch on market history (Novel Investor)

- Why saving is more important than investing (Pension Partners)