The Wall Street Journal had a story yesterday that highlights the dominance of U.S. stocks over the rest of the world in the past few years:

Since 2012 alone, the U.S. share of global stock market capitalization has risen from roughly 35% to just over 40% of the total.

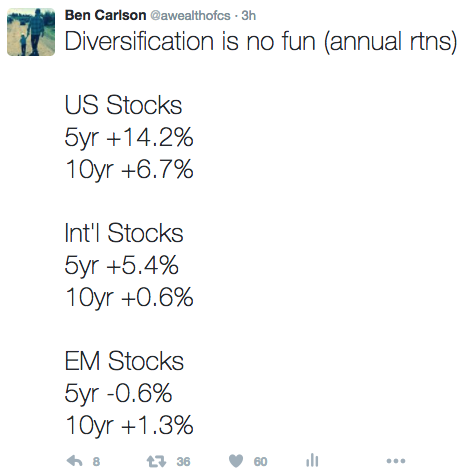

I tweeted out the following this morning, which provides the obvious reason for this shift:

U.S. stocks have slaughtered international markets throughout this cycle. I’ve had plenty of questions from investors asking me why they should ever own foreign stocks when they see these types of returns. It’s a legitimate concern. We humans are an impatient group so it can be difficult to see valid reasons for diversification when presented with performance numbers like this.

I’m reminded of a Howard Marks quote that sums this up nicely when he said, “In the world of investing nothing is as dependable as cycles.”

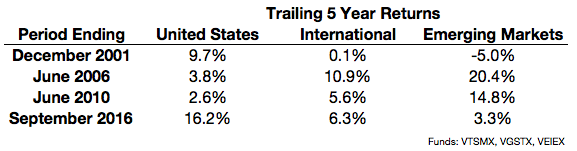

I took a look back a 5 year trailing returns on three different Vanguard equity index funds — U.S., international and emerging markets — to show this cyclicality in practice:

The performance spreads in December of 2001 were fairly similar to the ones we see today. Those numbers had completely reversed by 2006 and stayed that way through 2010 until coming full circle today.

Despite these cyclical differences if you looked at the 15 year returns of these funds since 2001 they weren’t all that different:

- United States +7.8%

- International +6.3%

- Emerging Markets +7.3%

It’s easy to say that you’ll be happy only investing in U.S. stocks today because it feels much better when you’re invested in the best performer as opposed to the worst performer. It may not be all that easy when the cycle inevitably turns. And it will turn at some point. The U.S. doesn’t have a monopoly on stock market returns, profit growth, dividend payments, innovation or good ideas.

The problem for many investors is that they only want to be invested in the best performer so they end up chasing what’s worked well lately. Seeing these kinds of relative performance spreads invites the hindsight bias to allow us to assume we knew exactly what was going to happen.

The hardest part about cycles is that there’s no rhyme or reason to their length or magnitude. It’s certainly possible that U.S. stocks could continue their strong relative performance for a number of years. Or it could end tomorrow. No one really knows. Investors are a fickle bunch.

There are all sorts of intelligent-sounding reasons to avoid foreign stocks at the moment — stagnant economic growth, poor demographics, the European Union seems like a mess, political instability, etc. The thing to remember here is that the stock market has obviously already picked up on these things; that’s why market performance has been so poor. Things could definitely get worse, but it doesn’t have to get better for markets to recover; things just have to get less worse.

Bill Bernstein provides a nice summary on all of this:

First and foremost, don’t even think about trying to extrapolate macroeconomic, demographic, and political events into an investment strategy. Say to yourself every day, “I cannot predict the future, therefore I diversify.”

Diversification is not fun, but intelligent investing shouldn’t be about having fun.

Further Reading:

Global Diversification: Accepting Good Enough to Avoid Terrible