Investors are worried about stock buybacks. The following comes from a recent Bloomberg piece:

Chief executive officers, who just announced the biggest round of monthly repurchases ever, executed about $550 billion of buybacks last year, according to data compiled by S&P Dow Jones Indices. That compares with a net $85 billion of deposits by customers of mutual and exchange-traded funds, the biggest gap since 2012, data compiled by Bloomberg and Investment Company Institute show.

If you sell a share of stock in the U.S. market, there’s a fair chance the buyer is the company that issued it — and it’s buyers who’ve been on the right side of the trade since 2009. Buybacks are helping prop up a bull market that is entering its seventh year just as investors bail out and head back to bonds.

The worry is that the stock market will immediately go to zero if companies cease to buy back their own shares. Before we get into the possibility of share buybacks eventually destroying the market, a little history lesson. In the early 1980s the SEC instituted a rule which made it easier for companies to buy back their own shares of stock. Before then it was much easier for companies to simply distribute cash back to shareholders via dividends. That’s why the dividend yield was much higher in the past. Buybacks have since skyrocketed and are now larger than dividend payouts (although some of this has to do with the fact that many buybacks are used to dilute stock options granted to employees).

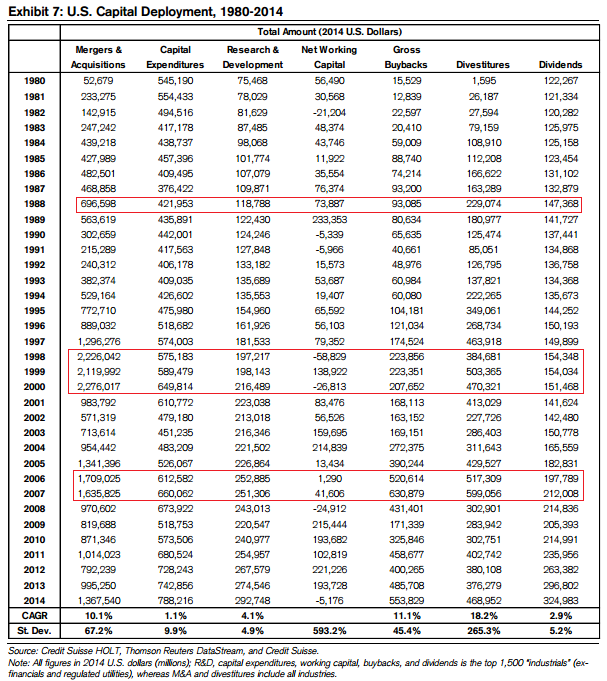

Investors focus on dividends and share buybacks, but corporations can also use cash flows for capex, mergers and acquisitions or R&D. Michael Mauboussin, an expert on capital allocation decisions, has shown that M&A activity is actually larger than dividend and buyback payments combined:

M&A is by far the largest use of capital, but it is very cyclical, ranging from a low of less than 1 percent of sales in 1980 to almost 30 percent at the peak in the late 1990s. M&A activity tends to be greatest when the economy is doing well, the stock market is up, and access to capital is easy. As a result, companies frequently do deals when they can, rather than when they should.

Mauboussin provides an accompanying chart that shows this in detail:

I’ve highlighted a few different points in the various cycles since 1980 to show that capital deployed by companies tends to top out at the peaks. Not only do companies do deals when they can, rather than when they should, they also do buybacks when they can, rather than when they should. Both are fairly cyclical along with the markets and economy.

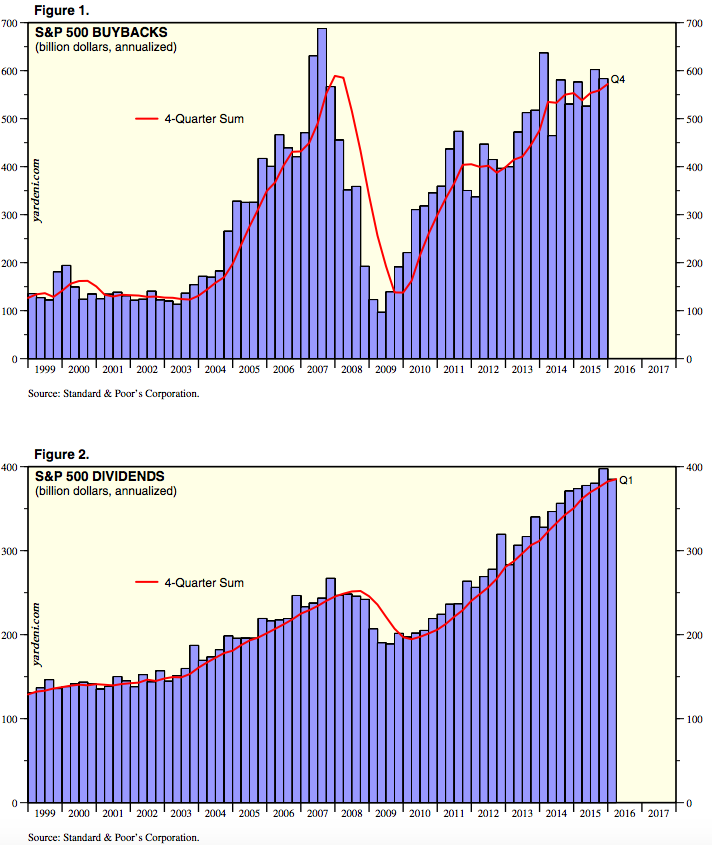

One of the biggest criticisms of buybacks is that corporate leaders tend to buy and sell at the wrong times. This data from Yardeni Research on the track record of total buybacks and dividend payouts tells the story:

It’s obvious that dividends are far more stable and companies typically buy back more shares as markets rise and fewer shares as they fall.

Yes, these companies appear to be horrible at timing the stock market, but this probably has more to do with the fact that they have more capital to deploy at the peaks in the cycle than they do during the downturns, so that’s when the money flows into buybacks.

And yes, dividends are more stable, but companies also run the risk of borrowing money to prop up their dividend payout to keep up the appearance that they are healthy when it’s possible that money could be spent in other areas during a downturn.

The problem with the buyback story is that the narrative would be totally different if all of that money was being used as dividends. We would be seeing headlines about how mom and pop are propping up the market by re-investing their dividends back into their mutual funds. In the grand scheme of things buybacks and dividends are basically identical to the end investor (see Stock Buybacks Demystified).

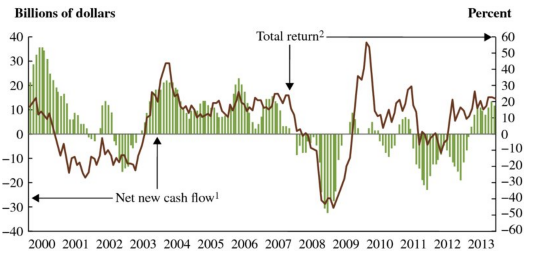

The cyclical nature of the share buyback chart above reminds me of this graph on mutual fund flows that shows individual investors also badly mistime market cycles when they deploy capital into the equity markets:

As we are all well aware by now, fund contributions tend to increase as markets rise and decrease as they fall. It makes no sense, but that’s what happens when emotions drive financial decisions.

Of course companies will be making fewer buybacks when markets go down. That’s what the majority of investors do. If everyone was disciplined and bought more when markets were falling they wouldn’t fall nearly as much as they do.

The problem is that there’s no way to tell when these numbers become too high or unsustainable. It’s more of a coincident rather than leading indicator. And saying buybacks are propping up the market is kind of like saying cash flows are propping up the market. There are so many variables here to consider that boiling this down to one figure — buybacks — is far too convenient.

Buybacks require some nuance beyond the headlines that tell investors that “they’re propping up the stock market.” When the market falls, buybacks will too. If your crystal ball tells you when the former will happen it will give you a good idea on when the latter will occur.

Maybe the main takeaway here is that there are lots and lots of subpar investors out there — from individuals to institutions to corporations and the leaders of these organizations making capital allocation decisions. Studies show that most mergers and acquisitions tend to perform poorly. The same underperformance typically applies to the average IPO when companies go public.

The best thing most investors can learn from this data is the fact that it’s generally a bad idea to sell more of your assets after they have fallen a great deal and buy more or your assets after they have risen a great deal.

Everyone knows this but that doesn’t make it easier to put it into practice.

Sources:

Buybacks at $46 Billion Dwarf Everything in U.S. Market (Bloomberg)

Capital Allocation – Updated (Credit Suisse)

Ben, thanks for the post. I agree with the overall point about not being able to time the market, but was gaffed a bit when I saw you wrote this “buybacks and dividends are basically identical to the end investor” Your statement may be true to investors in tax protected accounts but I would not assume that is the norm. From an average investors perspective buybacks are better as they don’t destroy their value through taxes. The buyback vs dividend explained http://www.hitinvestmentsllc.com/stockbuybackadividendalternative/

That’s valid. I guess I was thinking about tax deferred accounts, but there’s an obvious advantage to buybacks with a longer holding period. I guess it really matters whether or not the company is making timely buybacks or not.

While that is a classic, finance textbook argument, it ignores the fact that paying owners of an asset a cash dividend makes them free to make their own re-investment decision with those proceeds. Management is substituting their judgment that I as an owner of XYZ want to own MORE of XYZ with the cash instead of some other investment opportunity that I have available. There are many cases when I manage my own portfolio where I believe that I can re-invest the cash (after taxes) much better than management can. If I end up deciding that XYZ is, in fact, the best place for my investment capital, then I can go ahead and purchase those shares.

Since management teams have historically shown this pro-cyclical tendency to buy their own shares (and other companies) at precisely the wrong time in the cycle, I prefer my own investment decisions over theirs. In addition, I prefer the management discipline that comes alongside a dividend payout, though the stigma attached to slashing a dividend payout has diminished since the financial crisis.

I encourage you to read this article on why the dividend may be dead – http://www.hitinvestmentsllc.com/endthedividend/

What the stock buyback does over the dividend is it lets YOU decide when you want to sell your investment and re-invest elsewhere not when the company wants to distribute a dividend. You still have your ability to re-invest, its just that you are in control.

Well…that was an awesome post. Well done Ben, very interesting as usual.

thank you

Hi Ben. Fantastic post. Very grateful to learn from your investment ideas. If I’m an investor deploying capital to a Trend Following fund I want the manager to buy higher highs and sell lower lows. In this scenario, Does selling more of my assets after they have fallen a great deal and buying more of my assets after they have risen a great deal is a good idea?

The difference is that a trend follower typically has stops so they don’t get to the point of riding a position all the way down and then selling it. More here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2015/07/my-thoughts-on-gary-antonaccis-dual-momentum/

Allow me to summarize this post: buy low, buy into declines, and sell high.

I love buying as a stock that I already own declines in price. I feel like I am buying something on sale. I never sell when a stock is declining because I am almost always adding to it, assuming I have additional funds to invest.

The major problem I see with buybacks is that a company may wish to raise its price this way, but a larger market decline would lower their price anyway, so that money has been vaporized, instead of going to mom and pop. And no, mom and pop would not just reinvest that into more stock, they’re retired and need those dividends to live on, so the two are not equivalent.

More investors re-invest than you assume. In 2015 investors re-invested almost $600 billion of dividends and capital gains back into mutual funds.

“use cash flows for capex, mergers and acquisitions or R&D.” –

Or, executives and members use it as an extraction tool to benefit themselves. The poster child of this is IBM. Unless of course anyone thinks that IBM is near bottom then now would be a great time to buy!?