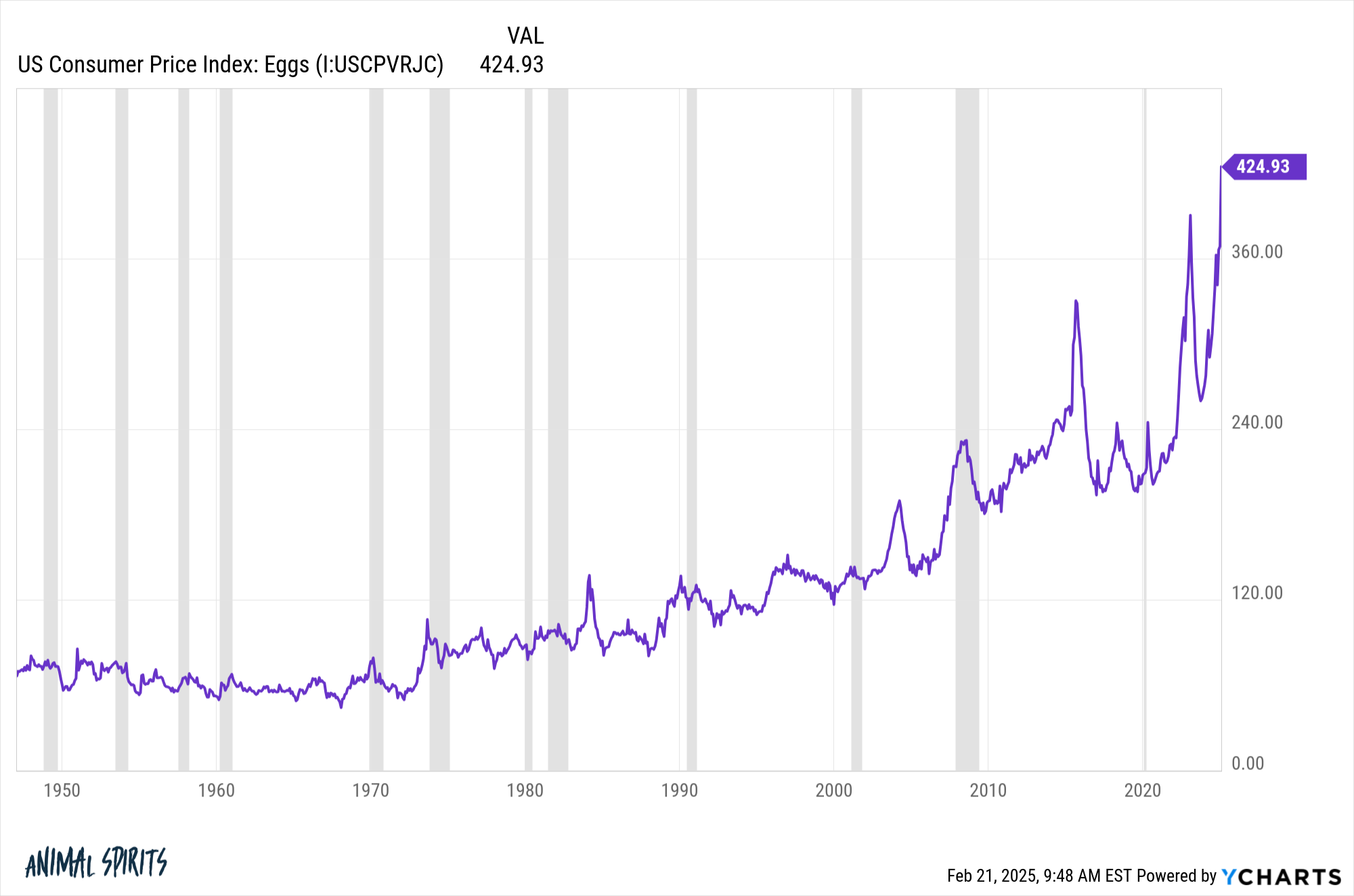

The hottest chart in the markets right now is not Nvidia, Fartcoin or one of the quantum computing stocks…it’s the price of eggs:

It looks like a chart of Bitcoin, Gamestop or the hottest AI stock on the street.

Since 1947, the price of eggs has grown at an annual rate of 2.4%, more than one percent lower than the overall annual inflation rate of 3.5%.

But over the last five years egg prices have gone up an en extraordinary 15.5% versus the overall inflation rate of 4.1%. Egg prices have more or less doubled in the past year.

A nasty strain of bird flu has impacted our egg-laying friends, constrained supply, and raised prices. It’s estimated that more than 100 million hens have been lost since the bird flu broke out in 2022. Things are getting crazy at the grocery stores.

This is from Bloomberg:

Grocery stores from New York to Chicago and Los Angeles have already limited purchases, while Waffle House added a temporary egg surcharge of 50 cents per unit.

The situation has gotten so dire that at a busy Whole Foods in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, the egg shelves were entirely empty on Tuesday evening, rendering purchase-limit signs redundant.

Egg prices have become the newest member of the inflation zeitgeist this decade. There are memes like this on social media all the time now:

It’s not just social media. I’ve had plenty of conversations with people about rapidly rising egg prices, a lack of supply and, for some, a struggle to find eggs at the store.

Obviously, higher prices at the grocery store are painful to your bottom line. Eggs are a good source of protein so it’s understandable why people are so up in arms about paying more at the checkout counter.

But there’s something else going on here. Egg prices are highly volatile. Eventually one would expect prices to come back to Earth. When that happens it’s not like people are going to rejoice. The pain of higher prices is always worse than the joy one receives from lower prices.

Daniel Pulter, a professor at Purdue University, studied weekly egg sale data in California to determine how the changes in price impacted consumer demand. Ori and Rom Brafman sum up Pulter’s work in their book Sway:

Now, traditional economic theory holds that people should react to price fluctuations with equal intensity whether the price moves up or down. If the price goes down a bit, we buy a little more. If the price goes up a bit, we buy a little less. In other words, economists wouldn’t expect people to be more sensitive to price increases than to price decreases. But what Putler found was that shoppers completely overreacted when prices rose.

It turns out that, when it comes to price increases, egg buyers are a sensitive bunch. If you reduce the price of eggs, consumers buy a little more. But when the price of eggs rises, they cut back their consumption by two and a half times.

Egg prices have an asymmetric demand profile.

When prices drop people buy a little more. But when prices rise they cut way back on egg consumption.

People overreact to price gains because losses sting twice as bad as gains feel good. You could call this irrational, but I prefer to think it’s just who we are as humans–it’s in our DNA.

This is why loss aversion is the most important concept in all of finance.

It shapes your actions, overreactions and perception of risk.

That feeling of loss aversion never goes away, so the trick is finding ways to deal with real and perceived losses in a way that keeps your emotions out of the decision-making process.

Further Reading:

Why the Stock Market Makes You Feel Bad All the Time