I bought a Peloton exercise bike during the early days of the pandemic.

It’s convenient and the technology is pretty neat.1

But I never would have purchased shares in the company. I have a rule of thumb that anything new that’s fitness-related is a fad. I’ve seen far too many fad diets and fancy exercise equipment or videos come and go over the years.

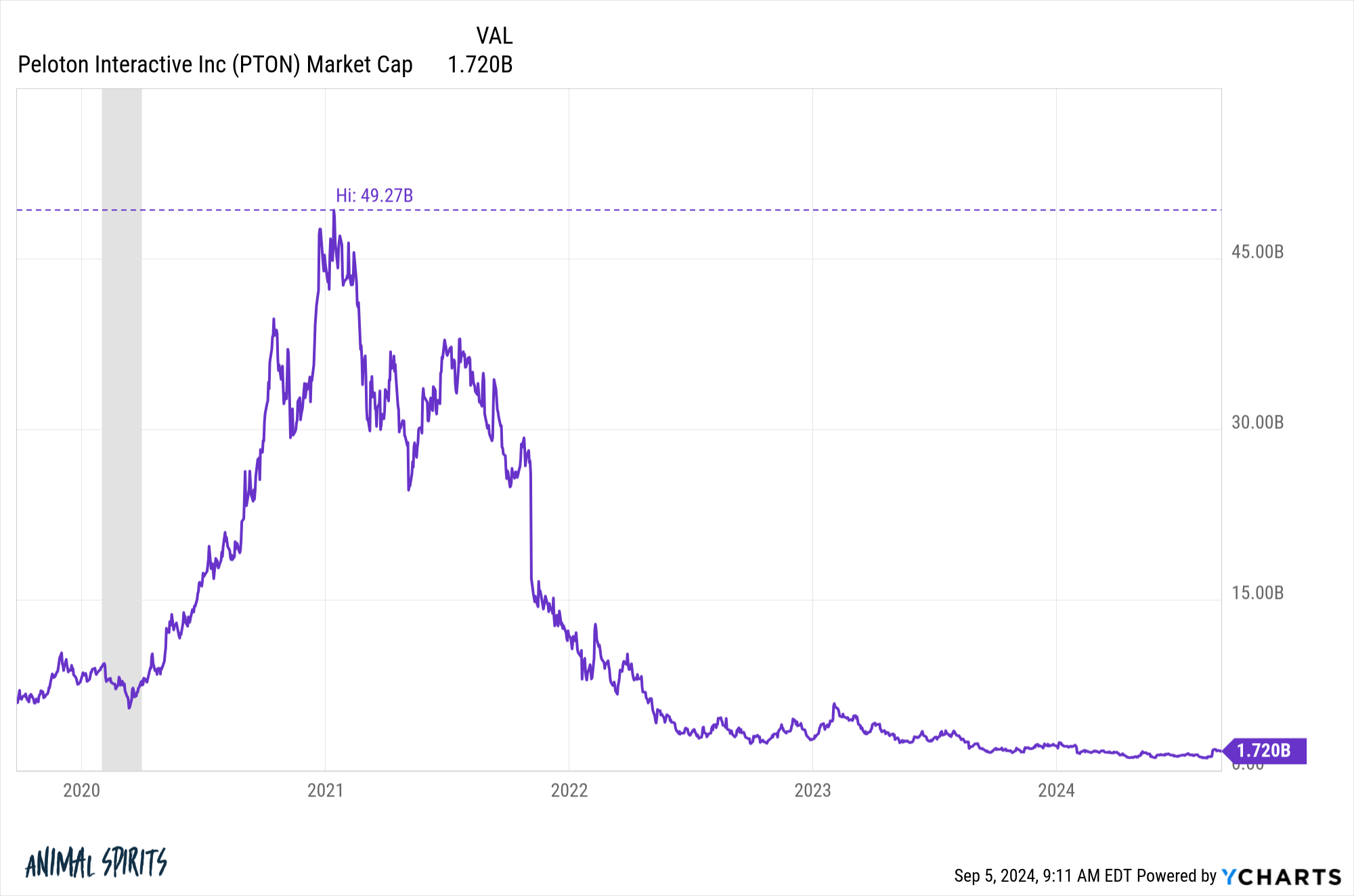

John Foley, the former CEO of Peloton, didn’t see it this way. As he watched the market cap of the company skyrocket from $7 billion pre-pandemic to nearly $50 billion a little more than a year later, Foley told his board Peloton would be a $1 trillion in 15 years.

They responded, “Don’t say that again. It makes you sound like an idiot.”

The board was right.

Peloton shares crashed once things got back to normal and all of the demand was done being pulled forward.

The stock is 97% off its all-time highs.

Foley was once worth a billion dollars (on paper) but lost basically everything. The New York Post recently wrote a profile about Foley’s rise and fall. Even though he’s moved on from the company, Foley is still optimistic about Peloton’s value:

But he has no interest in taking a company public again. “[Peloton shares] went from $170 to $2 … with that type of delta, I don’t trust the public markets to get the pricing right… [Peloton is] a $40 or $50 company, from my perspective today,” he said. (The current price is around $4.50) “The contract of the public markets getting a valuation right is broken.”

Peloton is a sub-$5 stock. Foley believes it’s a “$40 or $50 company,” which is a huge discrepancy. He blames the public markets.

To be fair, Peloton did get caught up in the speculative mania of the pandemic days but this is ridiculous. If he really believes Peloton is that undervalued, he should be getting as much capital as possible to buy shares or take the company private.

Foley’s outrageous thoughts on market pricing dovetail nicely with Eugene Fama’s recent Financial Times interview.

Fama created the efficient market hypothesis.

No one actually believes markets are perfectly efficient, not even Fama:

Fama is surprisingly phlegmatic when it comes to defending his life’s work, echoing the famous British statistician George Box’s observation that all models are wrong, but some are useful. The efficient market hypothesis is just “a model”, Fama stresses. “It’s got to be wrong to some extent.”

“The question is whether it is efficient for your purpose. And for almost every investor I know, the answer to that is yes. They’re not going to be able to beat the market so they might as well behave as if the prices are right,” he argues, his chicken wrap now efficiently devoured. Some of the backlash against the efficient market hypothesis may simply be down to hang-ups around the word “efficient”, which Fama admits he can understand. “I just couldn’t think of a better word. It’s basically saying that prices are right.”

Markets aren’t completely efficient but most investors should act like they are. I agree with that sentiment.

This quote from Fama is the one John Foley needs to hear: “If prices are obviously wrong then you should be rich.”

Stock prices are rarely “right” but they are right more often than most investors think. And if they were so clearly wrong all the time it wouldn’t be so hard to beat the market.

But beating the market is hard!

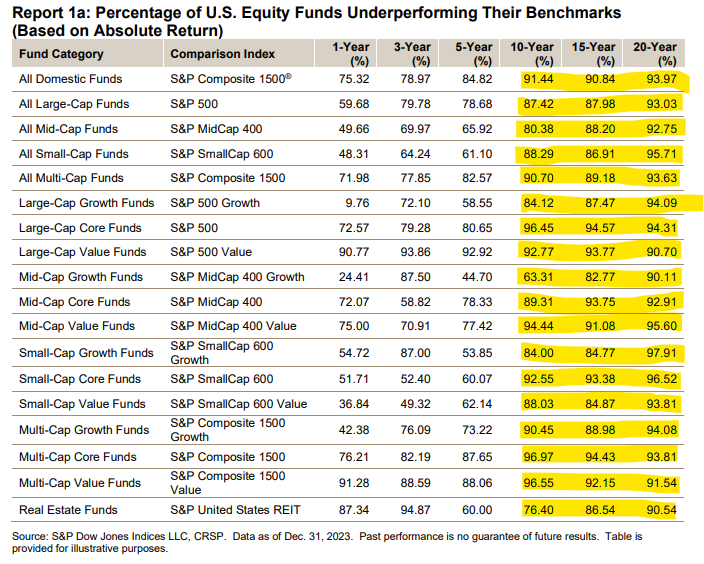

Just look at the numbers:

Professional money managers find it nearly impossible to beat the markets over 10, 15 and 20 years.

In that same interview, there was a quote from AQR’s Cliff Asness about how markets have actually become less efficient over time:

“I think [markets] are probably less efficient than I thought 25 years ago,” Clifford Asness, a hedge fund manager and a former research assistant to Fama, admitted to the FT in an interview last year. “And they’ve probably gotten less efficient over my career.

This doesn’t seem to add up. If markets are becoming less efficient, why are they also becoming harder to beat?

Luckily, Asness just published a new paper for the Journal of Portfolio Management that lays out his thesis in more detail. It’s a long piece. I read the whole thing (not to brag).

Here’s the main summary:

I believe markets have gotten less efficient over the 34 years since the data in my dissertation ended. I believe it’s likely happened for multiple reasons but technology, gamified 24/7 trading on your phone, and social media in particular are the biggest culprits.

I agree with this sentiment. The speed of market moves has made things more macro-inefficient, even if securities pricing is still relatively micro-efficient. So there is more volatility but it’s still very difficult to pick the winners.

Asness says this will make it more lucrative for investors who can stick with proven strategies over the long haul but it’s also harder to stick with those strategies in the short-term.

Thinking and acting for the long-term remains your highest probability of success in the markets.

Unfortunately, it’s harder than ever to have a long-term mindset.

Michael and I talked about efficient markets and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Flash Crashes Are Getting Faster

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- What we believed (Humble Dollar)

- Don’t tell me business isn’t personal (Downtown Josh Brown)

- Wealth is a single player game (A Teachable Moment)

- The cycle of financial manias (Safal Niveshak)

- Money market funds are not a free lunch (Oblivious Investor)

- 3 things you don’t know about Josh (The Big Picture)

- History has not been kind to the kings (Irrelevant Investor)

- Dating apps and demographics (Kyla’s Newsletter)

- An oral history of Super Bad (Vanity Fair)

Books:

1I really only use it now in the winter because that’s when I can’t jog in the cold Michigan weather.