A reader asks:

Ben always shares the long-run returns for stocks, bonds and cash. It’s essentially 10%, 5% and 3%. I know past is not predictive, blah, blah, blah but am well aware that cash has the lowest prospective returns of the main asset classes.

Knowing this full well, I still want to keep 10% of my portfolio in cash in retirement so I can sleep at night. Would a 60/30/10 portfolio really be that much worse than a 60/40?

I like this question because it gets down to the idea of optimization vs. behavior.

Emotions always win out over spreadsheets which is why understanding the lesser parts of yourself is so important as an investor.

Cash does have the lowest expected return of all the main asset classes. Stocks and bonds are riskier than cash which is why they should have higher expected returns.

I have no problem with a behavioral release valve in your portfolio as long as you understand the trade-offs.

I have reviewed the historical long-run returns for stocks, bonds, and cash on numerous occasions, so let’s look at some more recent performance numbers.

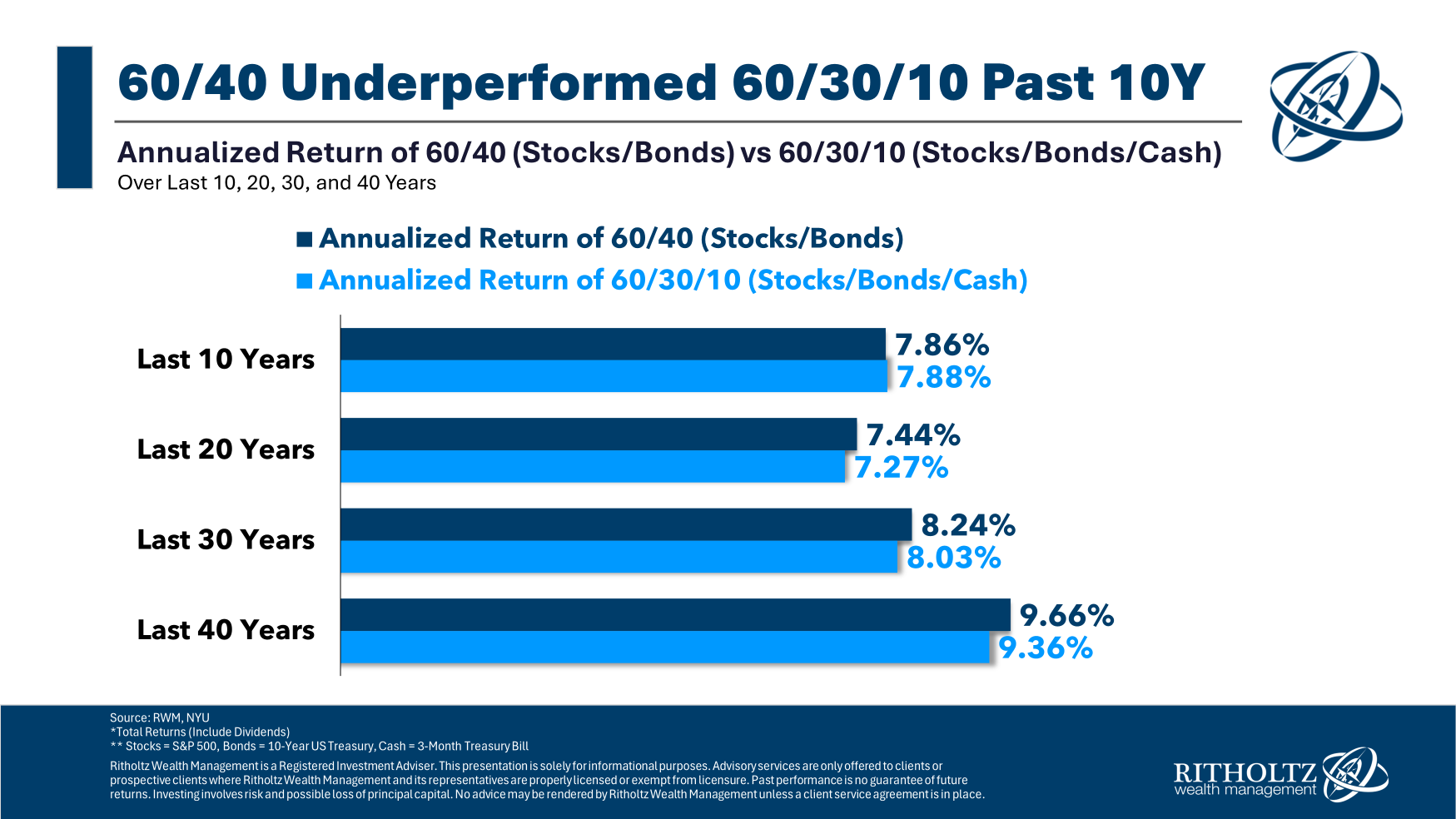

These are the annual returns1 in the 10, 20, 30 and 40 years ending 2023 for both a 60/40 portfolio and a 60/30/10 portfolio:

The returns for the more cash-heavy portfolio have actually been better than the 60/40 portfolio over the past 10 years. That makes sense considering we just lived through the worst bond bear market in history.

Bonds have had better returns over the past 20, 30, and 40 years, but the annual returns are not markedly better for a 60/40 portfolio than a 60/30/10 portfolio over the long term.

You give up some return but it’s not the end of the world.

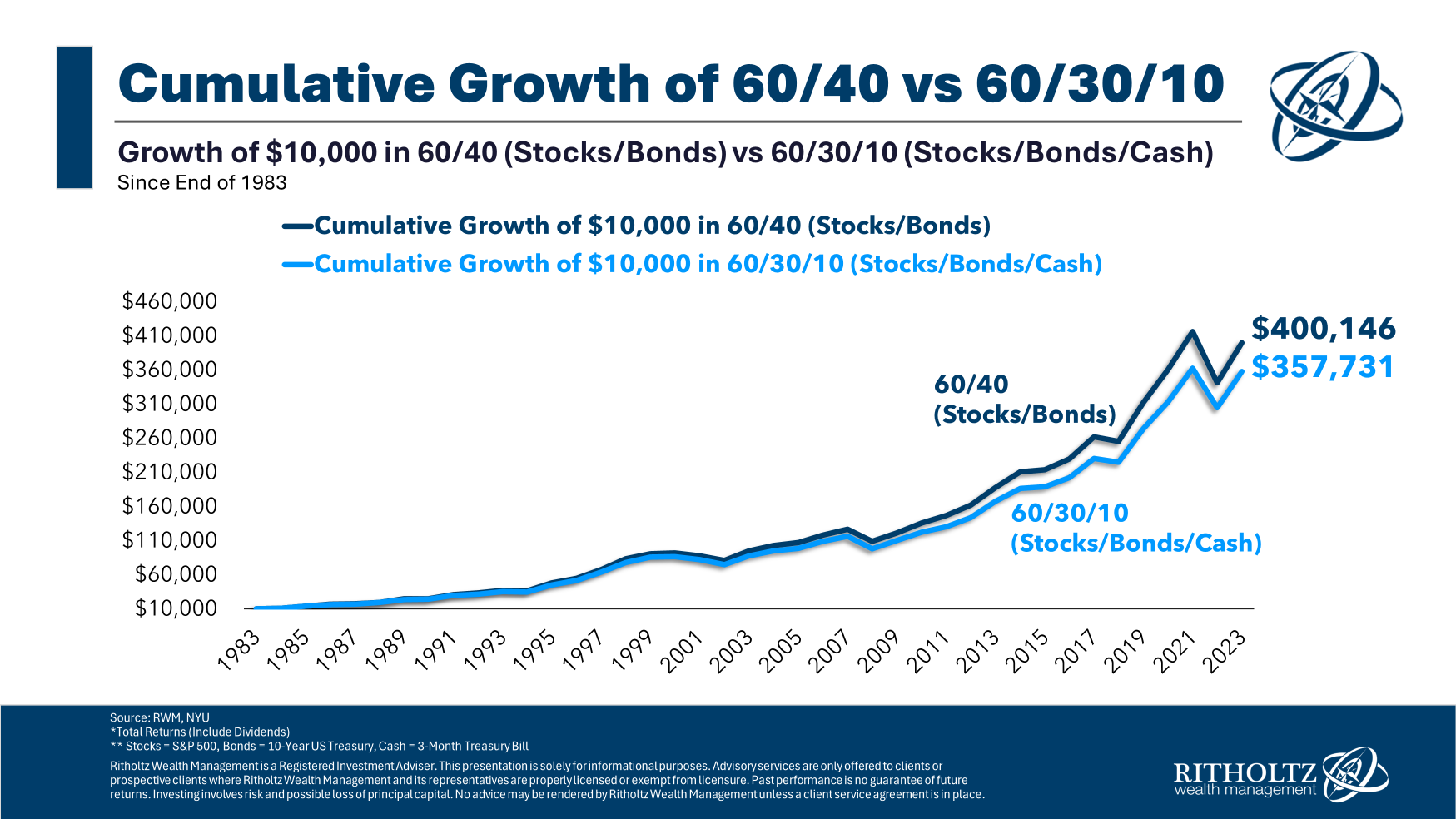

Here is a look at the growth of $10,000 in each portfolio over a 40 year time frame:

You would have ended up in a better place if you didn’t have the cash drag, but again, it’s still relatively close. And the gap would be smaller over shorter time frames.

I’m not a fan of going to portfolio extremes. Investors who try to get out of the stock market completely by going to cash and then getting all the way back in the stock market usually fail. That’s not investing; it’s speculation.

There’s a difference between going all in or all out and carving out a small allocation in your portfolio for behavioral purposes. If having that 10% piece of your portfolio allows you to stay invested in the other 90%, that’s a win.

Many investors have a hard time ever getting to a place where they can admit they need a behavioral release valve. Knowing thyself is a huge part of the investing process.

There is no such thing as the perfect portfolio but if one did exist most people probably wouldn’t be able to stay invested in it anyway.

The suboptimal strategy you can stick with is far superior to the optimized strategy you can’t stick with. The right allocation is the one that matches your risk profile, time horizon, and temperament.

Long-term returns are only useful if you have the ability to stick it out during the short-term.

We talked about this question on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Bill Sweet joined me on the show again to discuss questions about paying down a mortgage to refinance it later, donating stock to charity, ETFs vs. mutual funds and how to diversify your tax situation.

Further Reading:

A Short History of the 60/40 Portfolio

1I used an annual rebalance for both allocations.