A reader asks:

Do you think the stock market is a form of a Ponzi scheme and eventually investors will figure that out and quit investing? The average dividend payout for all stocks is a little over 1%. Back in the 1958 the average lifespan of a corporation was 58 years, but is now down to around 15 years. So, why are people investing in the stock market? The answer is they hope to make money by selling a piece of paper (stock certificate) to someone else (the greater fool) at a nice profit. If there is no one to buy your piece of paper, you will not make money in the long run.

The short answer is, no, I do not think the stock market is a form of a Ponzi scheme.

In a Ponzi scheme old investors are being paid off by money “invested” by new investors. There is no business plan. There are no revenues or profits being created.

The stock market is a collection of corporations. Those corporations make products and perform services. Consumers and other businesses pay money for those products and services.

That results in revenue. Some of that revenue is used to pay the costs of running the business but whatever is leftover can be used to pay down debt, buyback shares of stock, pay dividends to investors or be reinvested back into the business.

The profits of a business accrue to the equity investors in those corporations. So as the sales, dividends and earnings grow over time, the stocks are worth more money.

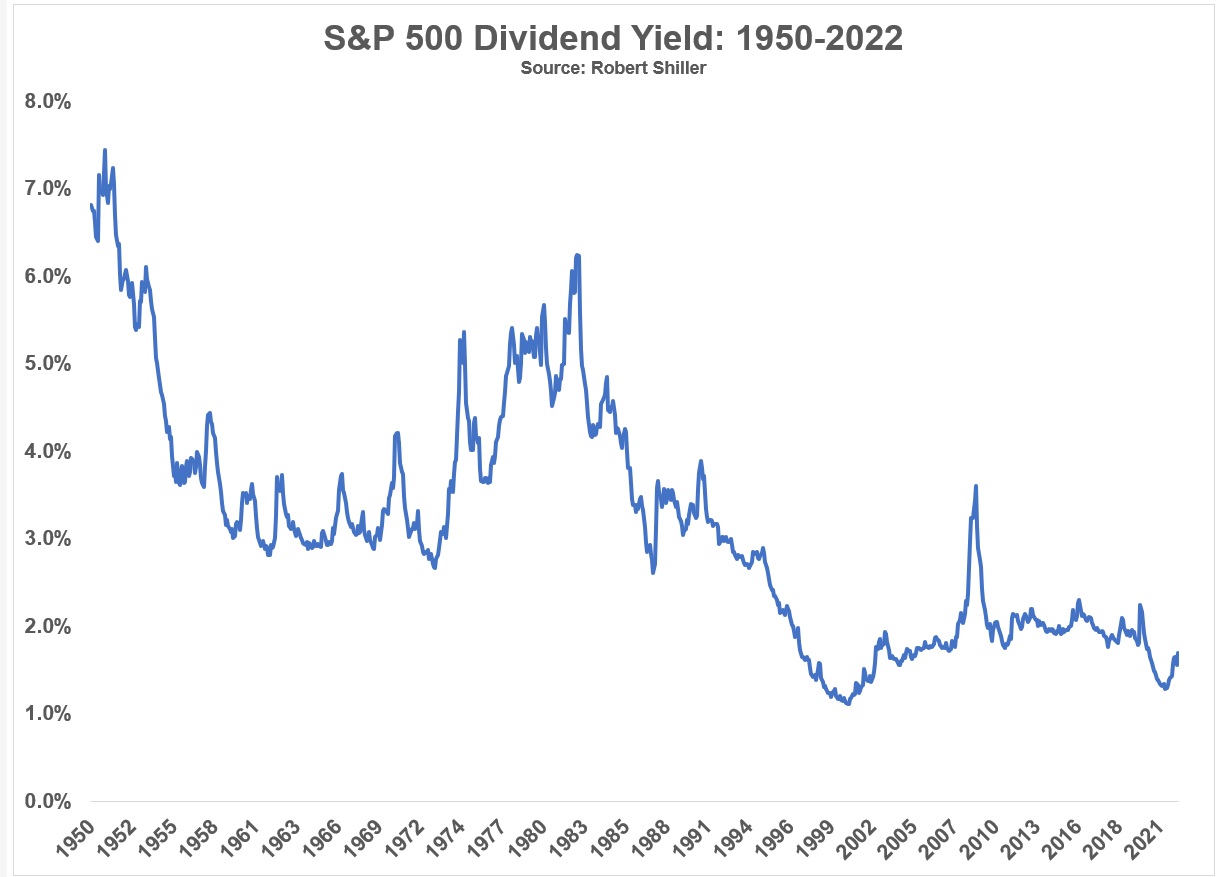

It is true that the dividend yield is much lower today than it was in the past. This is the dividend yield on the S&P 500 going back to 1950:

The dividend yield was 7% in the early-1950s!

It’s now more like 1.6%.

There are a number of reasons for this.

The stock market was still wildly undervalued in the aftermath of the Great Depression and WWII. The 1950s bull market took care of that.

The stock market is certainly more overvalued today than it was back then.

Dividends were also a more prominent feature for investors. Most investors preferred bonds back then so stocks were forced to pay higher dividends to entice people to invest in stocks.

But it’s also true that stock buybacks were not really part of the capital allocation decision for management back in the day. It wasn’t until laws were changed in the early-1980s that CEOs were able to more easily buy back their own shares.

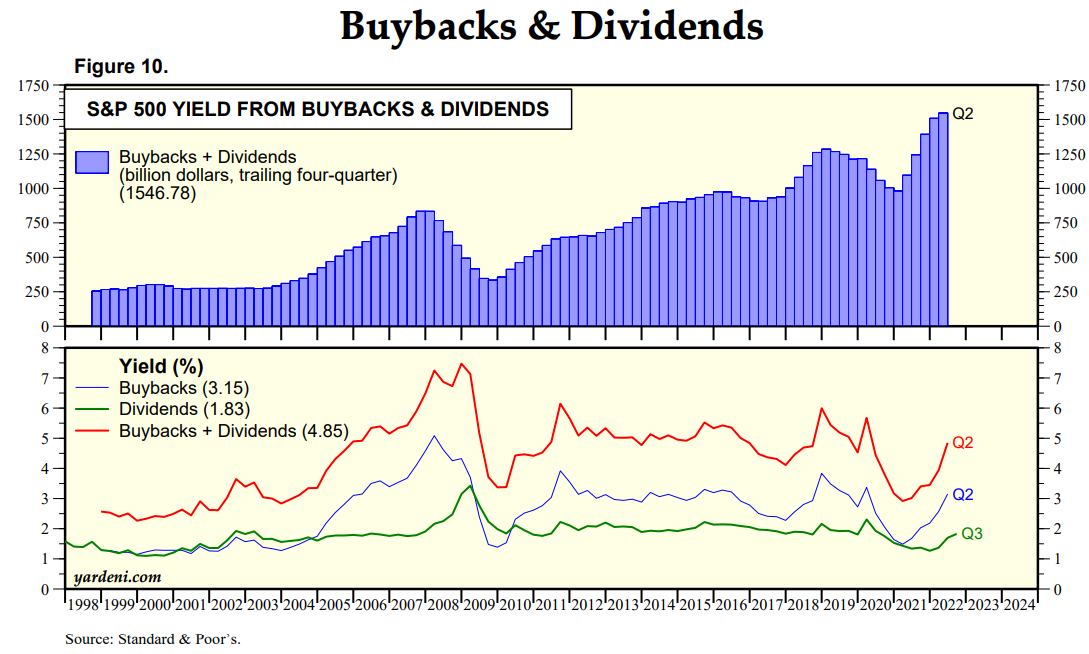

Yardeni Research publishes a chart of both dividends and buybacks to show the combined yield from both:

It’s close to 5%.

Dividends and buybacks are effectively the same thing so that cash has simply gone in a different direction.

Buybacks are far more cyclical than dividends but you can see this yield has hovered between 4-7% for much of this century.

Yield also doesn’t tell the whole story.

Dividends per share were $1.15 back in 1950. Today dividends are more than $60/share. That’s compounded annual growth of almost 6% per year.

Earnings growth was similar over this time, growing from $2.34/share in the 1950s to around $190/share today. That’s a little more than 6% per year.

The average inflation rate over that time is around 3.5% per year. This means earnings and dividends are growing at nearly 3% per year more than the rate of inflation.

That’s a pretty good deal if you ask me.

It’s also true that companies don’t last nearly as long as they did in the past.

Geoffrey West looked at the long-term data for his book Scale:

- 28,853 companies traded on U.S. stock market from 1950-2009. Almost 80% of those companies (22,469) were gone by 2009 (through buyouts, mergers, failure, etc.).

- Fewer than 5% of companies remain over rolling 30 year periods.

- The risk of a company dying does not depend on its age or size as the probability of a 5-year-old company that dies before turning 6 is the same as that of a 50-year-old company reaching age 51.

- The estimated half-life of U.S. publicly traded companies was 10.5, meaning half of all companies that go public in any given year will be gone in 10.5 years.

- There was just a 12 percent survival rate for the firms on the Fortune 500 list in 1955.

I see this development as a positive, not a negative. This is innovation in action.

Owning a piece of the stock market allows you to profit from the new up-and-coming businesses that are putting the old ones out to pasture.

Now, supply and demand are part of the equation.

If more people want to own stocks, the amount investors are willing to pay for them (ie, valuations) will rise.

If fewer people want to own stocks, the amount investors are willing to pay for them will fall.

But even if fewer people wanted to own stocks in the future it’s not like the profits would stop accruing. You would probably just see more corporations buy back their own shares of stock and reap the rewards of an ever-shrinking shareholder base.

Owning shares in the stock market gives you access to the profits, dividends, sales, growth, innovation and ingenuity of the biggest and best companies in the world.

If Charles Ponzi’s scheme gave his investors access to that his name would not be used in a derogatory way.

Further Reading:

How the Stock Market Works