Magician Gustav Kuhn once performed a simple magic trick to learn why people are so susceptible to sleight of hand.

He took a small red ball and threw it in the air, catching it with one hand. He then did it again a second time very quickly. But on the third throw, the ball never came down. It disappeared.

It was a mystery.

Where did the ball go?

It didn’t actually disappear into thin air. Kuhn never actually threw the ball the third time. He hid it in his hand, only pretending to throw it, just like every dog owner has done at least once in a game of fetch.

But many of the people watching this trick were sure the ball left his hand. Two-thirds of the participants in Kuhn’s experiment experienced the illusion of the ball being thrown into the air on the third attempt even though it never happened.

When Kuhn showed them the video they were astounded the ball never actually left his hand. It felt real. Many assumed it must have somehow stuck to the ceiling.

The key to the trick?

It wasn’t the hidden ball. It was Kuhn’s eyes.

As he threw the ball, his eyes followed the path it would have taken. It was the eyes that told the lie. In another version of the trick, Kuhn kept his eyes down and it wasn’t nearly as effective.

The trick doesn’t work without expectations. When Kuhn and his researchers looked more closely at video of the audience’s reactions, most people were looking at his face, not the ball.1

In his book, Experiencing the Impossible, Kuhn concluded, “Our brain uses a really clever and almost science-fictional trick that prevents us from living in the past: we look into the future. Our visual system is continuously predicting the future, and the world that you are now perceiving is the world that your visual system has predicted to be the present in the past.”

In other words, our expectations of the future are based on patterns from the past. Our brain builds narratives based on recent experiences.

This same process occurs when investors are trying to figure out the markets. The pattern that controls those market narratives is almost always price and price alone.

When stocks are falling it’s easier to become increasingly more bearish.

When stocks are rising it’s easier to become increasingly more bullish.

Call it pattern recognition, recency bias or sleight of hand in our brains but nothing changes narratives in the stock market like a change in price.

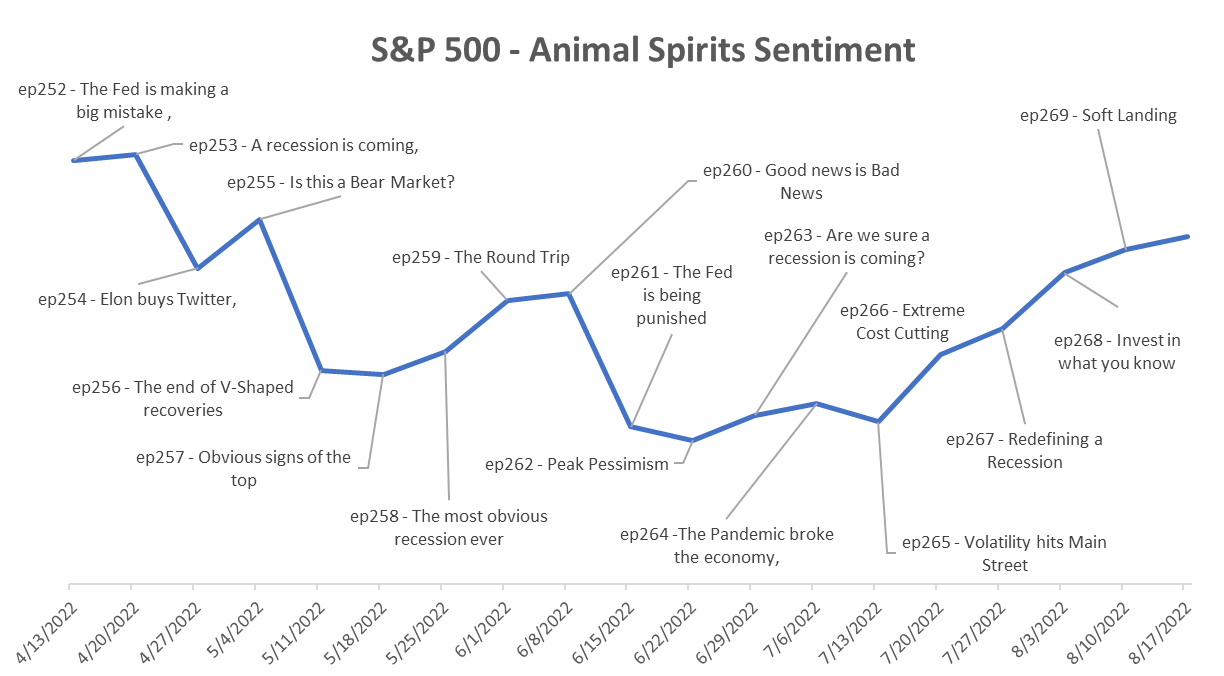

A podcast listener alerted us to the idea that our episode titles did a nice job gauging market sentiment these past few months so we charted them on a weekly graph of market prices:

The titles got more bearish the further stocks fell and have softened in recent weeks during the rally (Peak Pessimism kind of nailed the bottom).

The prevailing narratives 2-3 months ago in the stock market were as follows:

- The stock market is pricing in an imminent recession or we’re already in one.

- The Fed has lost control of inflation.

- Without the Fed put there’s nothing stopping the stock market from falling 40-50%.

These narratives all made sense at the time because the stock market was down almost 25%. When prices are down it’s always going to be easier to talk yourself into every bearish argument.

Now that the market has rallied 15%, here are some new narratives gaining steam:

- It’s possible the Fed could orchestrate a soft landing.

- A recession is no longer guaranteed.

- Inflation is improving.

- Well even if we do go into a mild recession, the Fed will probably step in and lower rates.

All it took for a change in sentiment was higher prices.

If stocks continue to rise, this new narrative will become even stronger. If the rally peters out and stocks resume their descent, those previous narratives will return.

Why is this the case? Because we’re addicted to stories. Stories can help your brain avoid discomfort.

Think about the crypto market. It’s the narrative-price relationship on HGH.

When prices are rising it feels like a game-changing technology. Everyone in the space sounds like a genius. Each new project sounds better than the last. And it feels like prices will go straight up forever.

When prices are falling it feels like a solution in search of a problem. Everyone in the space sounds like an idiot. Each new project feels even more likely to fail. And it feels like prices will go straight down forever.

Not everyone gets caught up in this narrative tug-of-war. There will always be contrarians.

The hard part about handicapping the markets is sometimes going with the flow and sticking with the prevailing narratives and trends is the right move. As Jeff Bezos once said, “Contrarians are usually wrong.”

And sometimes it pays to go against the grain.

The problem, as always, comes down to timing.

Michael and I discussed how price drives narratives in the stock market and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video (taped at a company offsite at Barry Ritholz’s house):

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Being a Contrarian is Easier in Hindsight

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Are you trying too hard? (Hot Takes)

- How to lie with statistics (TKer)

- When data fails (Dollars and Data)

- Was that the bottom? (Bull & Baird)

- The biggest life event no one talks about (Belle Curve)

- How Super Bad came together (The Ringer)

1If this video doesn’t trick you it’s probably because I already gave it away before you watched it.