A reader asks:

I am a 29-year-old marketer with total annual comp of around $140k. Been aggressively investing for several years & maxing out my 401k ($216k), funding a Roth IRA ($2k) and saving in a brokerage account ($100k). I am typically a buy & hold investor. I’ve seen a 25% decline in my total portfolio since December as I am in aggressive & US-focused equities. Question: If my portfolio declines as it has over the past 6 months, am I still getting the benefits of compounding? I don’t think my brain fully comprehends the power of compounding so can you explain this in more detail.

You are not alone in finding the power of compounding confusing.

Our brains aren’t made to think in exponential terms. We are linear thinkers.

Let’s look at a simple example to show compounding in practice.

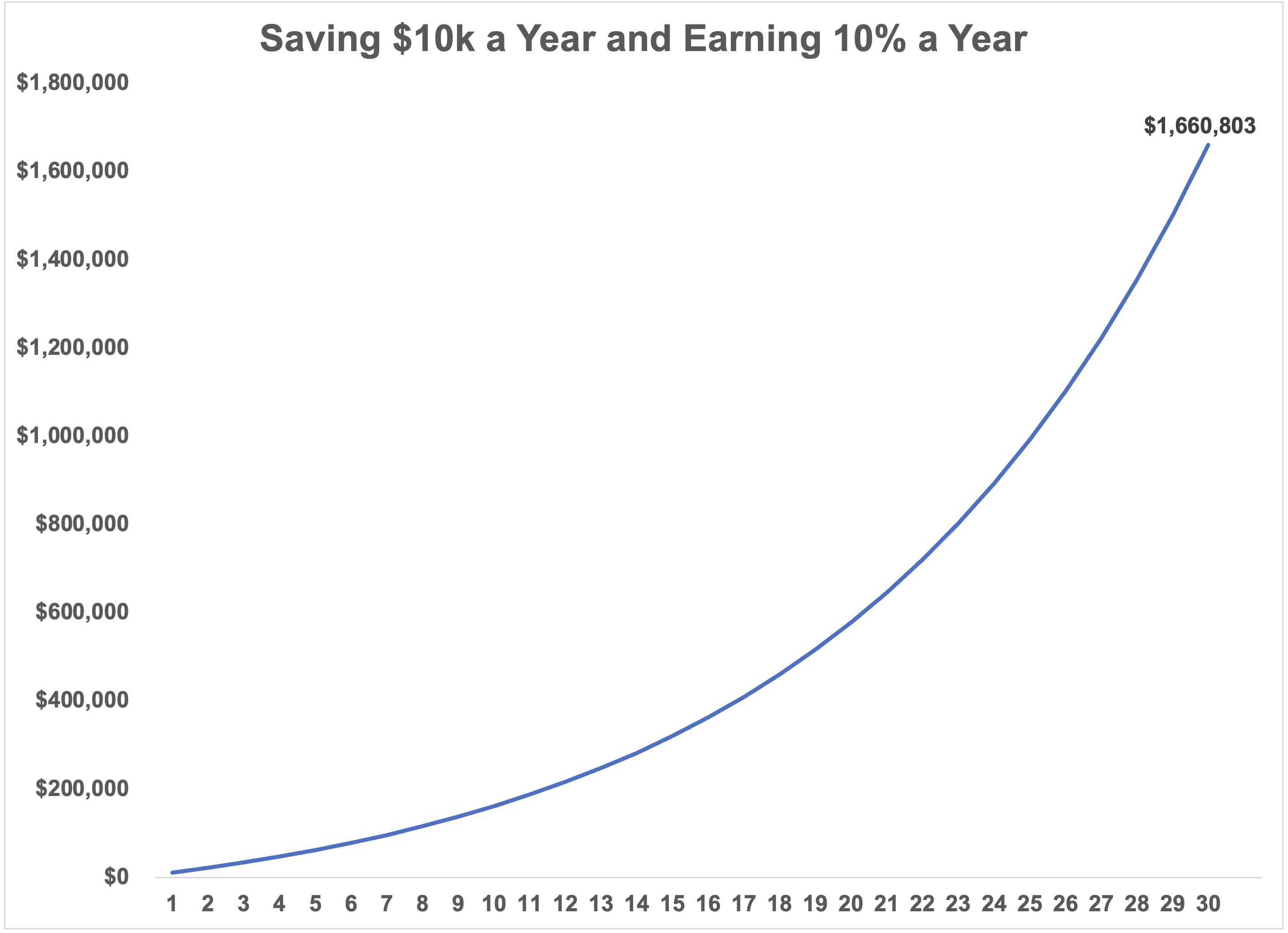

Let’s say you save $10,000 a year at the start of every year for 30 years and earn 10% on your money:

Not bad. You would have turned $300,000 into nearly $1.7 million.

Earning double-digit returns over 3 decades will do that for you.

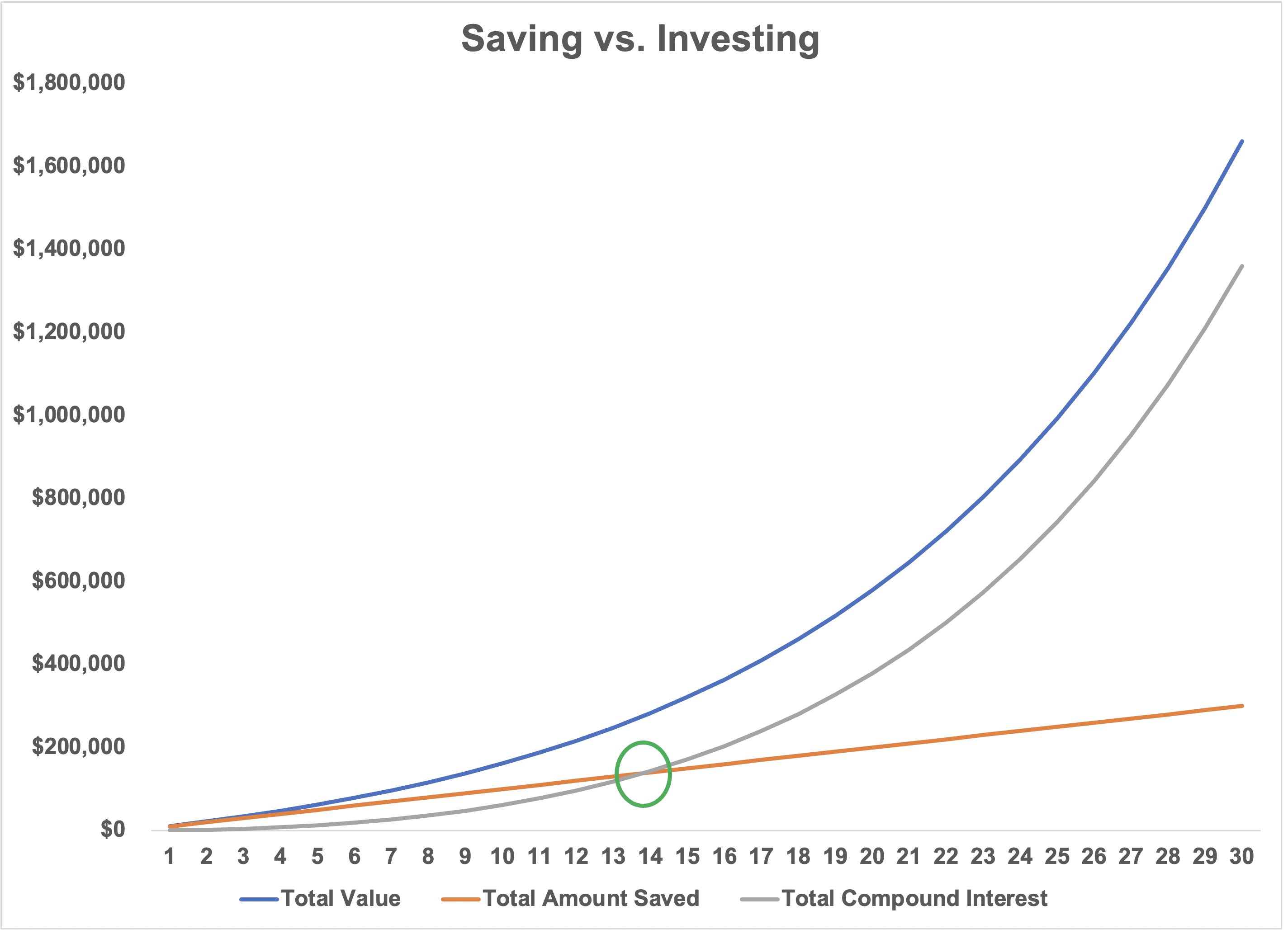

One of the worst parts about compounding is you have to be patient to see the greatest benefits.

In this example, your investment earnings don’t pass the amount you save until after year 14:

Up until that point, the amount you save matters far more than the amount you earn on your investments.

Compound interest is also backloaded in an example like this.

The total investment dollars earned here would be just shy of $1.4 million. But nearly 60% of those profits come in the last 6 years of the investment earnings.

This is why compounding only works through a combination of discipline and patience. You have to think in terms of decades to see the best results.

The problem with the real world is life does not work like an Excel spreadsheet. You cannot type in your expected returns and assume you will earn them year in and year out.

The stock market doesn’t work like that.

Compounding in a retirement calculator is neat and tidy.

Compounding in the stock market is messy and lumpy.

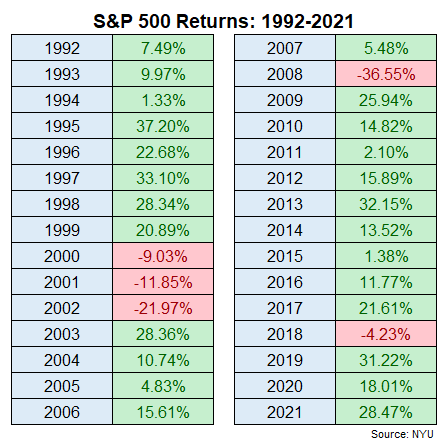

I don’t know if the stock market will continue to offer 10% annual returns going forward but it just so happens that if you look at the 30 year time frame from 1992 through 2021, the S&P 500 returned a little more than 10% per year.1

So let’s assume you put that same $10,000 at the outset of every year earning the actual returns in the stock market which were as follows:

Sometimes high, sometimes low but definitely not consistent from year to year.

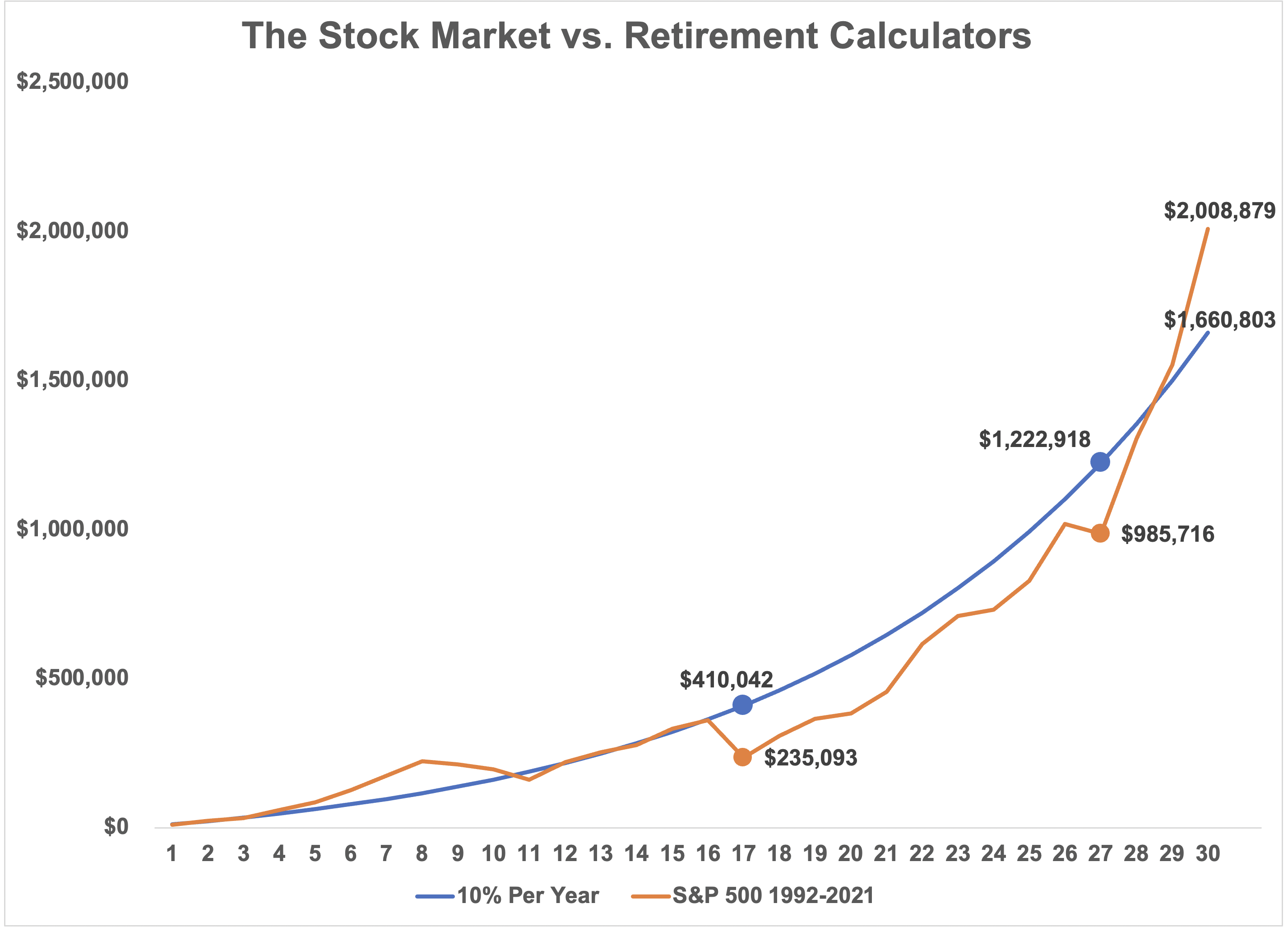

Now let’s compare dollar cost averaging into the stock market to a simple 10% per year return:

Even though the annual returns were the same over this 30 year period, the experience of a stock market investor was anything but smooth. You can there were many years in which investing in the stock market put you pretty far below the trendline.

But then stocks played catch-up in a hurry and ended up much higher than the consistent return stream.

It doesn’t always have to work like that.

Sometimes you get terrible returns at the end of your investing lifecycle instead of the beginning. The sequence of returns along with your start and end dates can play a large role in determining your real world outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of luck involved in this process in terms of the timing.

This is why you need to play the long game. A long time horizon can help smooth out any poor timing you may have through either mistakes or bad luck.

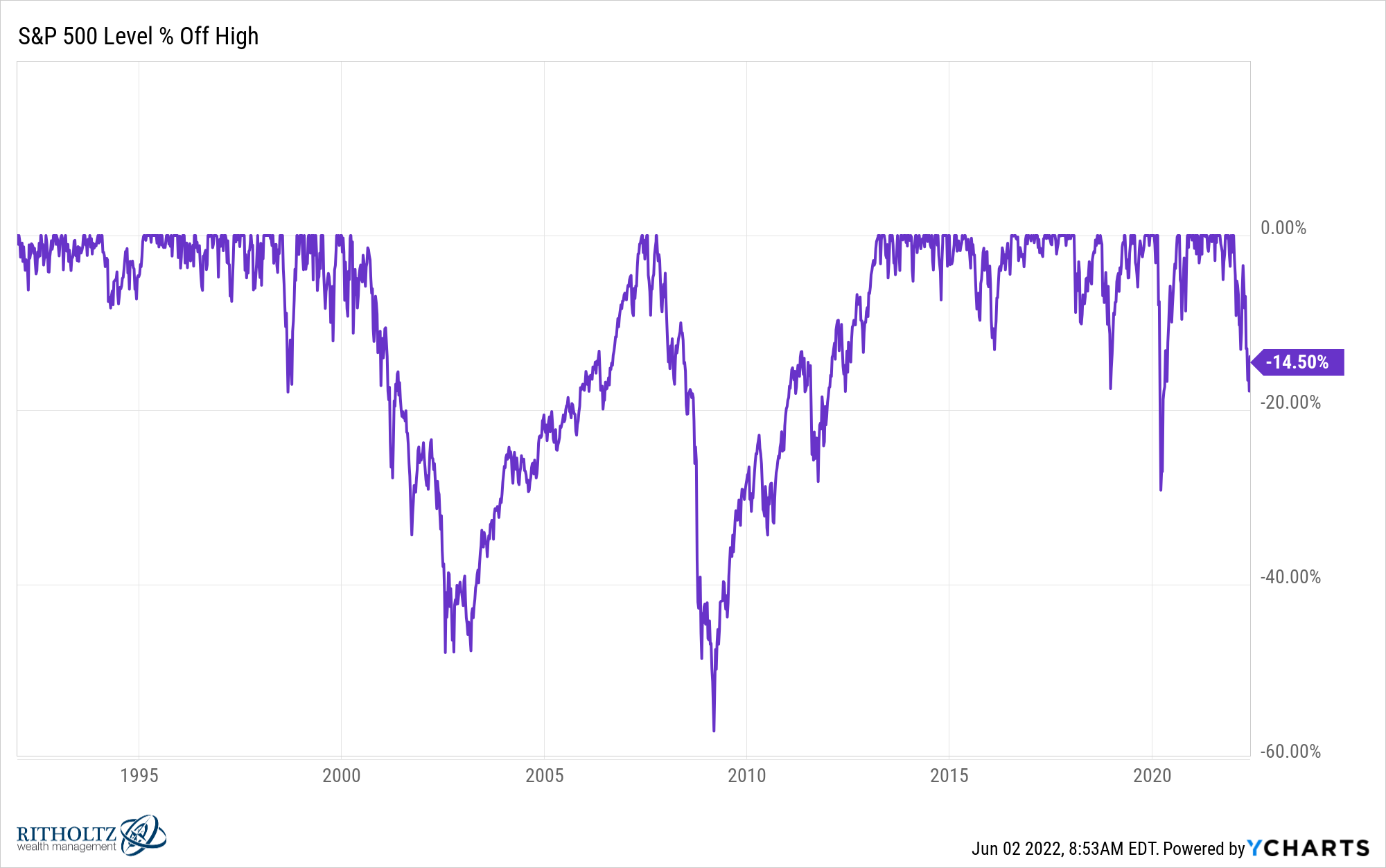

It’s also important to note that compounding in the stock market didn’t come easy. Here is the drawdown profile since 1992:

By my calculations the S&P 500 has experienced drawdowns of -11%, -19%, -12%, -50%, -15%, -57%, -16%, -19%, -13%, -10%, -20%, -34% and the current drawdown.

I wish there were assets that could guarantee you high returns with no downside risk.

One of the biggest reasons investors have earned 10% annual returns in the stock market over the long haul is because of the many painful corrections that occur along the way.

If there was no risk there would be no returns.

And the beauty of saving a decent chunk of your income at age 29 during a downturn is that’s how you juice your compounding over the long run.

The purchases you make early in your career when stocks are down will be some of your best investments 20-30 years down the line when compound interest really kicks in.

We talked about this question on this week’s Portfolio Rescue:

Taylor Hollis joined me as well to discuss changing your asset allocation in retirement, enrolling in your company’s stock purchase plan, some tips on writing and more.

Podcast here:

1If I wanted to impress you with finance terms I would have said “per annum” here but I’m not going to do that. There are rules here and rule #1 is no finance jargon.