After getting engaged my wife and I began having some deeper philosophical conversations about how we would run our joint finances. We were in our mid-to-late 20s at the time so I informed her I would like to put the majority of our retirement savings into the stock market.

This was obviously a topic initiated by yours truly since I am the personal finance nerd of the relationship but she was all for it. We covered our spending habits, budgeting, saving, debt, bill payments and how we generally planned on setting long term financial goals. It was a great talk and one I recommend every couple have at some point if they plan on staying together for the long haul. The fastest way to lose half of your money is not a stock market crash but a divorce so it’s a good idea to make sure you’re on the same page when it comes to your finances.

Since we both come from similar backgrounds when in terms of saving, spending, credit card debt and living below our means this was a pretty easy conversation considering how problematic finances can be for some couples. But there was one area where my wife needed some more clarity. And that was the topic of investing our retirement savings in the stock market.

My wife, like most normal people, did not know much about the stock market except for what she heard on the news or saw on TV and in the movies. She did not give much thought to investing in stocks. So when I told her we would be saving the bulk of our retirement money in stocks (especially when we were younger) she was initially concerned.

Aren’t stocks extremely risky?

Isn’t this just gambling with our money?

Isn’t there a chance we could lose most of our money?

Shouldn’t we just play it safe?

Working in the finance industry, I’m no stranger to an Excel spreadsheet or PowerPoint presentation but I needed to put this explainer into plain English to avoid boring her and get my point across. What follows is more or less what I told her (and despite going through this exercise she still agreed to marry me if you can believe it).

The stock market is the only place where anyone can invest in human ingenuity. It is a bet on the future being better than today. Stocks can be thought of as a way to ride the coattails of intelligent people and businesses as they continue to innovate and grow. Short of owning your own business, buying shares in the stock market is the simplest way to own a slice of the business world.

The greatest part about owning shares in the stock market is you can earn money by doing nothing more than holding onto them. When companies pay out dividends to shareholders, you get cold hard cash sent to your brokerage or retirement account which you can choose to either reinvest or spend as you please. The stock market is one of the few places on earth where you can earn passive income without having to do any work whatsoever. All you have to do is buy and wait. And if global stock markets don’t go up over the long term you’ll have bigger problems on your hands than your 401(k) balance.

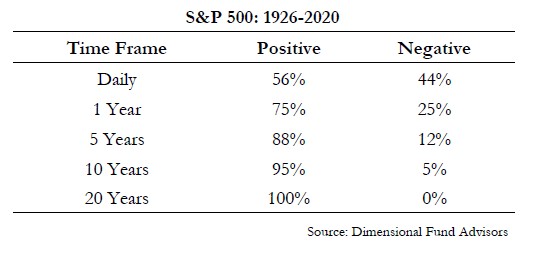

Many people compare the stock market to a casino but in a casino the odds are stacked against you. The longer you play in a casino, the greater the odds you’ll walk away a loser because the house wins based on pure probability. It’s just the opposite in the stock market.

The longer your time horizon, historically, the better your odds are at seeing positive outcomes. Now these positive outcomes don’t guarantee a specific rate of return, even over longer time frames. If the stock market were consistent in the returns it spits out, there would be no risk.

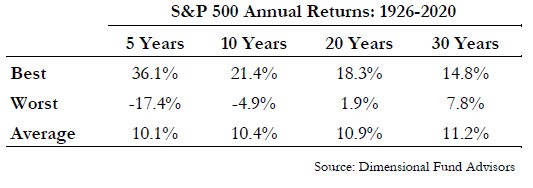

If there were no risk, there would be no wonderful long term returns. And because there is risk involved when owning stocks, your returns can vary widely depending on when you invest in the stock market.

It has been possible to lose money over decade-long periods in the past. Even 20 to 30 year results can see a big spread between the best and worst outcomes. However, it is worth noting that even the worst annual returns over 30 years in the history of the U.S. stock market would have produced a total return of more than 850%. This is the beauty of compounding. The worst 30 year return for the S&P 500 gave you more than 8x your initial investment.

The stock market is a compounding machine in other ways as well. Since 1950, the largest companies in the U.S. stock market have seen dividends paid out per share grow from roughly $1 to $60 by 2020. Profits have grown from $2 a share to $100 a share. Those are growth rates of roughly 6000% and 5000%, respectively, over the past 70 years or so, good enough for 6% annual growth for each. One dollar invested in the U.S. stock market in 1950 would be worth more than $2,000 by the end of 2020.

$10,000 dollars invested in the S&P 500 in the year:

- 2010 would be worth $37,600 by September 2020

- 2000 would be worth $34,200 by September 2020

- 1990 would be worth $182,300 by September 2020

- 1980 would be worth $918,500 by September 2020

- 1970 would be worth $1,623,500 by September 2020

- 1960 would be worth $3,445,000 by September 2020

I’m ignoring the effects of fees, taxes, trading costs, etc. here but the point remains that over the long haul, the stock market is unrivaled when it comes to growing money. And the longer you’re in it the better your chances of compounding.

Having said all of that, there is an unfortunate side-effect of this long term compounding machine. Stocks can rip your heart out over the short term. If there is an ironclad rule in the world of investing, it’s that risk and reward are always and forever attached at the hip. You can’t expect to earn outsized gains if you don’t expose yourself to the possibility of outsized losses. The reason that stocks earn higher returns than bonds or cash over time is because there will be periods of excruciating losses.

That $1 invested in 1950 would grow to $17 by the end of 1972 and subsequently drop to $10 by the fall of 1974. From there it would grow to $95 by the fall of 1987, only to drop to $62 over the course of a single week because of the Black Monday crash. That $62 would have turned into an unbelievable $604 by the spring of 2000. By the fall of 2002 that $604 would have been down to just $340. After slowly working its way all the way to $708 by the fall of 2007, over the next year-and-a-half it would be cut in half down to $347 by March 2009. By the end of December 2009 that initial $1 was worth $537, which is less than the $590 it was worth a decade earlier by the end of 1999.

So $1 growing into $2,000 sounds amazing until you realize the many fluctuations it took to get there. The stock market goes up a lot over the long term because sometimes it can go down by a lot over the short term.

The stock market is fueled by differences in opinions, goals, time horizons and personalities over the short term and fundamentals over the long term. At times this means stocks overshoot to the upside and go higher than fundamentals would dictate. Other times stocks overshoot to the downside and go lower than fundamentals would dictate. The biggest reason for this is because people can lose their minds when they come together as a group. As long as markets are made up of human decisions it will always be like this. Think about how crazy fans can get when their team wins, loses or gets screwed over by the refs. These same emotions are at work when money is involved.

How you feel about investing in the stock market should have more to do with your place in the investor’s lifecycle than your feelings about volatility.

This post is an excerpt from Everything You Need to Know About Saving For Retirement and was originally posted here on February 21, 2021.