In 2011, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen wrote one of the more prescient pieces of this century, called Why Software Is Eating the World. He laid out his reasoning behind the idea that technology is fundamentally changing the way we do business, likely for good:

My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley–style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

Andreessen listed a number of reasons for his theory:

- Technology can be delivered around the globe at scale.

- Billions of people use the Internet and own smartphones.

- These tools make it easier than ever to launch new businesses without huge upfront costs.

Andreessen was right, of course, but software has been eating the stock market also, and this trend has been in place for many years.

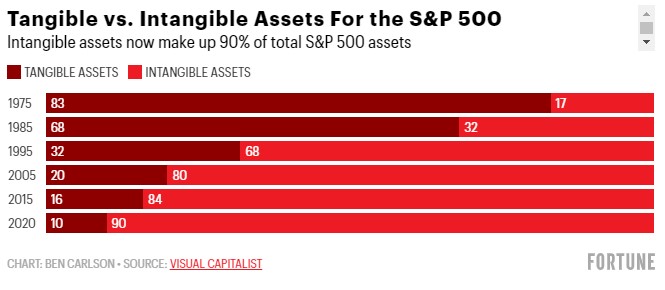

In the past, most corporations had balance sheets full of tangible assets, including things like land, buildings, equipment, and inventory. Now the majority of assets are intangible, things like patents, brand value, software, and customer data.

Look at that shift from 1985 to 1995 as the Internet came online in a meaningful way. The corporate balance sheet of today looks nothing like the one from the 1970s.

In 1980, seven of the 10 biggest stocks in the S&P 500 were energy corporations. Just one was a technology firm (IBM). The energy sector made up nearly 30% of the S&P 500 in the early 1980s. It’s now down to roughly 2.5% of the index.

Technology has taken energy’s place at the top of the heap as the largest sector, with a 24% weight. And that weighting is likely understated. For instance, the six biggest companies in the S&P 500 are all what most people would consider tech stocks or at least tech-adjacent companies—Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Tesla, and Facebook.

Collectively, these six stocks are worth around $8 trillion.

Yet Apple and Microsoft are the only two companies of the six that are technically listed in the technology sector. Facebook and Google are in the communication services sector. Amazon and Tesla are considered consumer discretionary stocks.

It may be semantics to debate which sector these companies belong in, but the point is technology is now firmly entrenched across the stock market in a bigger way than ever before.

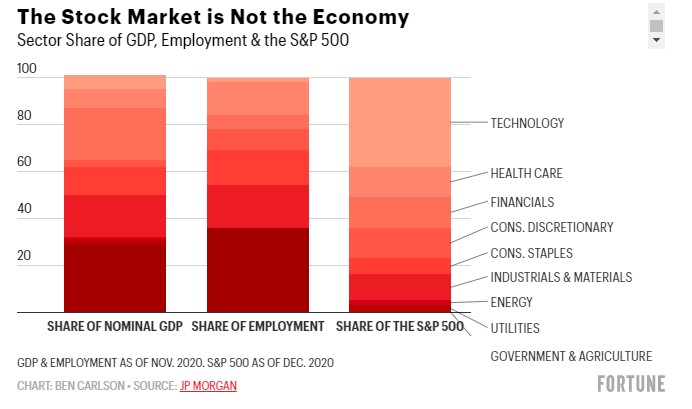

You can get a better sense of how the tech sector has swallowed the stock market by comparing it to the overall economy:

JPMorgan estimates the true weighting in the market for tech stocks is closer to 40%—while those companies account for 6% of nominal GDP and employ just 2% of the country’s workers.

Consider the fact that U.S. Steel was the first billion-dollar corporation in the early 1900s. In 1902, the company employed nearly 170,000 people. Instagram was sold for $1 billion to Facebook in 2012. At the time the company had just 13 employees.

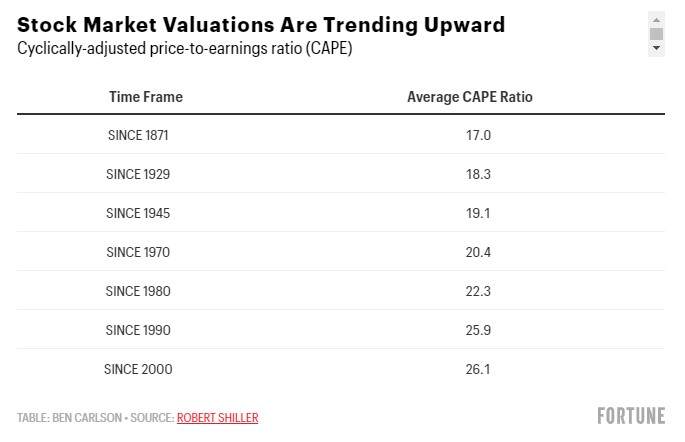

Technology has also had an impact on stock market valuations. Average long-term valuations have slowly moved upward over time as tech has become a bigger piece of the pie:

There are other reasons valuations have been trending higher over time—falling interest rates, the role of the Federal Reserve, lower costs to invest, and more professionalized investors, to name a handful.

But the growth in technology stocks and intangible assets has played a role here as higher growth, less-capital-intensive businesses tend to have higher valuations.

So what does this mean for investors going forward?

Because of the rise of intangible assets, earnings are far less relevant today than they were in the past. And expectations matter just as much or more than the actual fundamental numbers, especially in the short to intermediate-term.

Every successful investor’s job is to figure out where there are potential mispricings between fundamentals and expectations. When the market is filled with more technology companies, it becomes much easier for expectations to detach from fundamentals, in both good and bad ways.

This means investors should expect to see more booms and busts as people try to right-size their expectations for companies that could either change the world or crash and burn.

Markets will move faster. Technological innovation can create massive change in the world, but new and exciting companies also invite more risk-taking from investors.

More tech stocks in the market don’t guarantee higher returns for investors, but it likely means market cycles will speed up. Just last year the S&P 500 experienced the fastest bear market of 30% or worse—as well as the second-fastest full recovery from a 30% bear market.

With increased access to market data, computational power, and information, expect market moves to happen faster in the future.

This piece originally appeared at Fortune.