CNBC had a story this week about a $330 billion pension plan in Canada that is reviewing its allocation to bonds in light of the fact that yields are basically non-existent in fixed income right now.

How could they not?

If you’re an investor and you’re not at least considering doing something about the bond portion of your allocation you’re not paying attention.

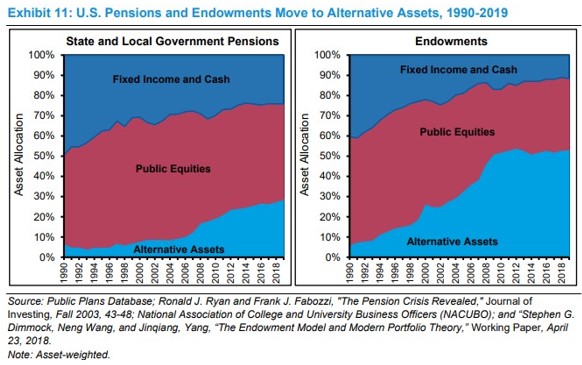

There has been a strategic asset allocation shift going on for institutional investors for some time now. You can see bonds and cash have slowly been giving way to alternative assets in recent decades for pensions and endowments (via Micheal Mauboussin):

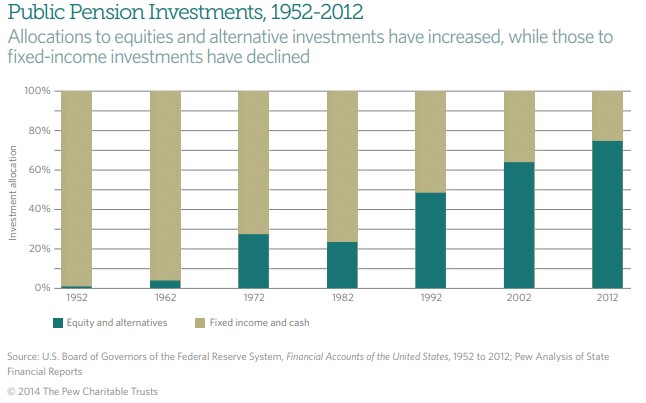

In fact, this shift dates back well before the 1990s. Prior to the early 1980s, most public pension plans were subject to strict regulations on their investment choices. The majority of the investable assets were in bonds because of these restrictions (via Pew Charitable Trusts):

Institutional investors have evolved in a number of ways since the 1970s beyond higher allocations to stocks and alternative assets.

According to the late-Peter Bernstein, it wasn’t until the 1973-1974 bear market that many of these huge pools of capital even benchmarked their performance to market indexes. And those that did use a benchmark, used the Dow Jones Industrial Average but didn’t include dividends in that assessment and used the Dow even when their portfolios were full of bonds.

It was a simpler time.

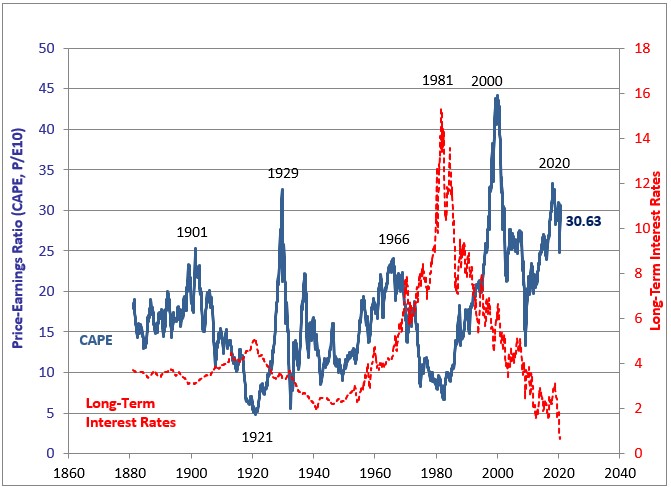

Institutional investors are more professionalized today but the market environment is harder than its ever been. The combination of low bonds yields and high stock valuations is without precedent:

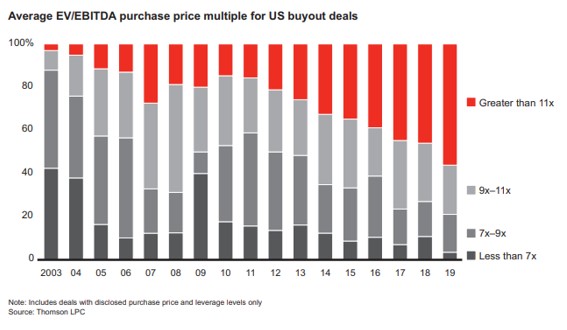

Private equity valuations have screamed higher as well:

Investors have to change their expectations at some point. There’s no getting around it.

The biggest question is this — does a change in expectations require a change in strategy?

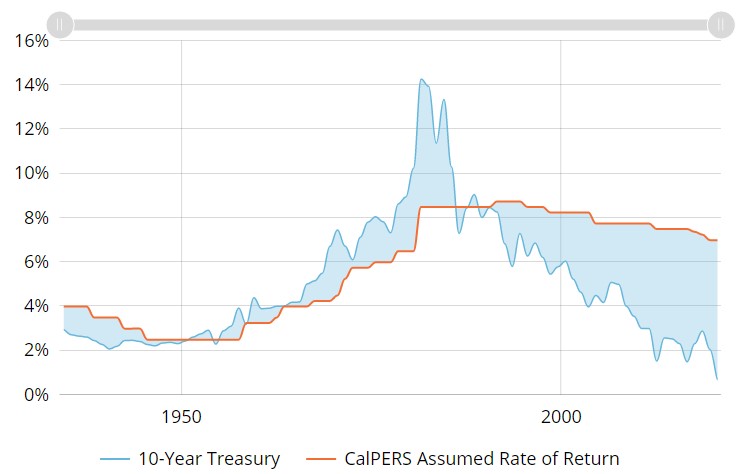

Or maybe for an organization like Calpers, the question should be — does a change in interest rates require a change in expectations? This is the expected rate of return for Calpers plotted against the 10 year treasury yield (via the Reason Foundation):

For many decades the expected rate of return was close to that of prevailing interest rates so not only was it a simpler time to be an allocator, but an easier time. That relationship has broken down in recent decades.

My first job in this business was with an institutional consulting firm where we helped manage money and create investment plans for pensions, foundations, endowments, and insurance companies. My boss would always lead his presentations to these investors with the following formula:

5% spending + 2% inflation = 7% return just to break even

Many foundations are required to spend 5% of their assets each year to keep their tax-exempt status. The stock market, private equity and venture capital have all picked up the slack for low -yielding bonds in recent years, but simply breaking even going forward might be as hard as it’s ever been.

I’ve been giving some Zoom talks in recent months to institutional investor groups and how to hit their return bogies is by far their biggest worry. Here are the options I laid out in a recent talk:

- Take more risks

- Change your asset allocation/investment strategy

- Lower your expectations

- Spend less (or fundraise more)

Taking more risk doesn’t guarantee higher returns and counterintuitively it could lead to lower returns if you give up on the strategy at the worst possible time.

The change in asset allocation has been happening for decades now and I would expect that process to speed up in a world with no yield. Like it or not, these investors are going to have to accept more volatility to reach their goals.

Lowering your expectations is an intelligent move for all investors at the moment but it’s not always the easiest pill to swallow.

Fundraising is to nonprofit investors as saving is to individual investors. This is one way many of these funds can make up for any potential shortfall from investment returns in the years ahead. Expect the fundraising efforts at nonprofits to ramp up.

The hardest decisions for many pensions and charities will have to come at an organizational level, not from the investment staff. There’s only so much the investment officers can do if these plans are underfunded or the nonprofits have made promises they can’t keep.

Many municipalities will be faced with difficult decisions in the years ahead from a political perspective if they come up short in their pension return assumptions.

Do they cut the benefits that were promised to employees?

Do they cut other government services to retain the ability to pay out pension benefits?

Do they raise taxes to pick up the slack and make more contributions to these plans?

None of these options are very appealing but this is where we’re heading. Investors face a challenging environment in the years ahead but the political decisions will be even harder than the market decisions.

Further Reading:

Something I’m Worried About