The Mongols ruled most of central Asia before their leader, Genghis Khan, led them on an ill-fated campaign into what is now Hungary, where he eventually died.

Two questions:

- Did these events happen before or after 151 A.D.?

- In what year did Genghis Khan die?

Before reading this question I had no idea what the actual year was.1 Assuming you were in the same boat as me, you likely guessed a number not too far from 151 A.D., even though that number was pulled from thin air.

Psychologist J. Edward Russo performed a similar test of 500 graduate students but instead asked them to use 400 plus the final three digits of their phone number as the year before guessing.

When that number fell within the range of 400-599, the average guess was that Kahn died in 629 A.D. But when the range of the first number was 1,200 to 1,399, the average guess was 988 A.D.

We unconsciously anchor to the original number we’re presented, even if it’s meaningless.

The same thing happens when you see the asking price for a house that’s for sale.

Real estate agents were asked to estimate the value of a home that was for sale. Half of the agents saw a listing price that was substantially higher than the actual listing price while the other half saw one that was substantially lower. The agents said they completely ignored the asking price but those who saw a higher asking price estimated the value of the home to be much higher than those who saw the lower asking price.

Daniel Kahneman has lots of examples of anchoring in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

When people move to a new city they use real estate prices from their previous city for comparison purposes. A study of people moving to new cities found those relocating from expensive cities rented more costly apartments than those who arrived from lower cost of living areas, and this relationship held after accounting for wealth, taxes and such. Even moving to a lower cost of living area, people used to paying a lot for housing continued to do so.

A grocery store in Iowa put Campbell’s soup on sale for 10% off. Some days they would put up a sign that read ‘limit 12 per person.’ Other days there was no limit. On days when the number of cans had a limit, people bought an average of 7 cans, twice as many as the average on the no-limit days.

If we’re given a number, whether it’s made up, a baseline, a limit or a floor it’s almost impossible for our brains to avoid using that number as a starting point.

The same is true of the stock market.

Think about how all over the map this year has been.

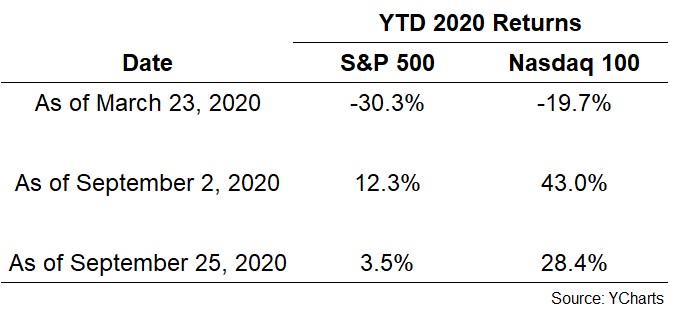

These are the year-to-date 2020 returns for the S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100 at various points this year:

It’s hard to believe this has all happened in the same year but here we are.

How you feel about the market can have a lot to do with the point at which your comparison begins.

Returns aren’t nearly as good as they were 3-4 weeks ago since we’ve had a minor correction but things are vastly better since the dark days of March.

If you’re constantly looking at the stocks in comparison to the bottom of a bear market it’s going to make you feel good about yourself for making some money or bad about yourself for missing out.

If you’re constantly looking at the market in comparison to all-time highs you’re going to be sadly disappointed most of the time. Since 1928, the U.S. stock market has closed at all-time highs on roughly 5% of all trading days. That means the other 95% of the time the stock market is in a state of drawdown.

So even when things are going well there is bound to be a disappointment because of the fact that your stock prices were once higher than they are now.

The stock market can make you feel awesome or terrible about yourself as an investor depending on the point at which you’re comparison begins.

It’s always useful to remind yourself that you’re not as smart or dumb as you feel depending on which starting point you use.

The stock market has the ability to make you feel great or awful depending on your time horizon.

Further Reading:

Why the Stock Market Makes Your Feel Terrible Every Single Day

1Khan actually died in 1227.