Stock market valuations may not make sense to a lot of people right now but valuations often don’t matter much in the short run.

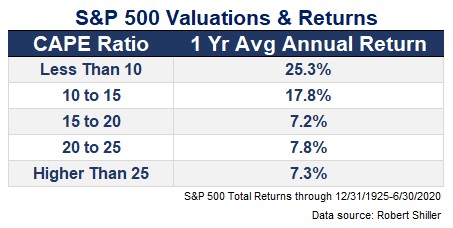

Take a look at the average one-year returns for the S&P 500 from various starting CAPE ratios going back to 1926:

Lower than average valuations show substantially higher average returns but the average one-year returns are actually better for the higher than 25 and 20 to 25 levels than the 15 to 20 subset for long-term PE ratios.

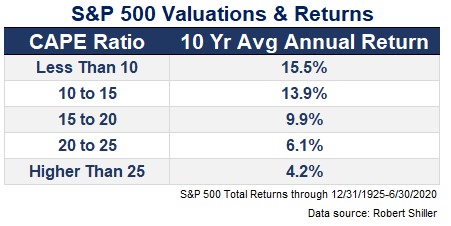

In the short run the stock market is a voting machine while in the long run it’s a weighing machine, as Benjamin Graham so eloquently put it. If we go out even further you can see the weighing machine takes over:

Now the relationship is clear as day — higher starting valuations lead to subpar long-term returns while lower starting valuations lead to above average returns.

With a current CAPE ratio approaching 30x yet again (it only got as low as 24x in March) investors should definitely expect lower long-term returns from current levels…right?

It depends.

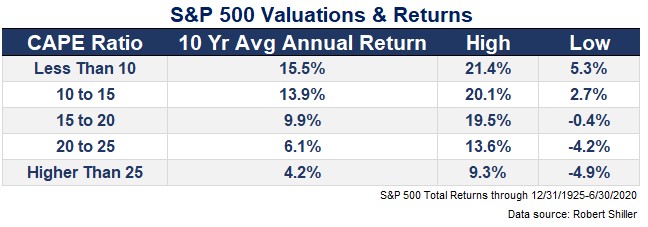

This certainly makes sense in theory but averages tend to mask the underlying individual outcomes over any single period. Here is this same data along with the maximum and minimum returns for these averages:

The general relationship still holds but you can see there have been relatively good outcomes from high starting valuations and relatively bad outcomes from low starting valuations. No one lives their life in the averages.

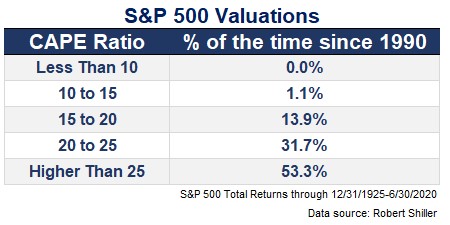

It’s also important to note the ‘less than 10’ category has only shown up in roughly 10% of all market environments since 1926. And if we look at the data since 1990, valuations have been skewing much higher for more than 30 years now:

There have been exactly four months where the CAPE ratio dipped below 15x since 1990. It hasn’t been lower than 10x since 1984. And 85% of the time the cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio has been above 20x since 1990. You could set a rule that you’ll only buy stocks when they hit dirt-cheap levels of the past but never see them get there.

Much more nuance is required in the valuation equation than at first glance.1 It makes sense to adjust your expectations with valuations higher but that doesn’t guarantee a specific outcome.

“It depends” isn’t the advice most people want to hear when it comes to their finances or career or really any big life decision but the world is rarely black or white when it comes to decision-making under uncertainty.

There are very few hard and fast rules of thumb when it comes to planning out your life because so much of the decision-making process depends on your circumstances, emotional make-up and skillset.

For example: Doesn’t it make sense to take some money off the table considering stocks have made up for most of their losses since the start of the crisis?

It depends.

What do your risk profile and time horizon look like? When do you need to spend the money? How good are your market timing skills? What’s your plan if the market keeps screaming higher?

When will you get back in if stocks fall? What are the tax implications of jumping in and out of the market? What do you know about stocks that other investors don’t already know?

Is your investment plan reliant on getting out of the market every time you’re worried about the current economic situation?

Doesn’t this feel like another potential bubble with stock market valuations at such lofty levels again?

It depends.

Interest rates are lower than they’ve ever been. The market is dominated by technology firms. Corporations have far more intangible assets than firms did in the past. Markets are also more mature and cost less to transact in.

Plus the Federal Reserve is more involved in the financial markets than they were in the past.

This doesn’t mean another bubble is impossible but it’s at least worth considering the other side before throwing around that word.

Doesn’t it make sense to hold your entire portfolio in stocks since the market always comes back?

It depends.

How willing and able are you to accept volatility? Do you understand the history of stock market booms and busts?

Do you need to fund your current lifestyle or other short-term goals in the immediate future? Do you have other sources of income than your investment portfolio to see you through a prolonged bear market?

Are you a net saver or net spender from your portfolio?

Doesn’t it make sense to avoid paying off your mortgage early since interest rates are so low and inflation is the friend of long-term debt repayments?

It depends.

What are your feelings towards debt? Do spreadsheet outputs matter to you when making big financial decisions?

What would you regret more — missing out on potential investment gains or owning your home free and clear?

Doesn’t it make sense to buy rather than rent since renting is just paying someone else’s mortgage?

It depends.

Do you understand all of the ancillary costs involved in homeownership? Do you require the flexibility to move in the coming years for family, life circumstances or career purposes?

Do you understand the fact that real estate isn’t always the best investment option? Did you run the actual numbers on renting vs. buying in your area?

Doesn’t it make sense to buy a starter home when you’re young to build equity?

It depends.

How long do you plan on living in your starter home? Do you understand the switching and transaction costs involved in the home-swapping process? Do you realize how difficult it can be to build equity in your home since the first few year’s worth of payments goes almost entirely to interest expense?

Do you understand leverage works both ways in the markets?

Are you ready to become a homeowner and accept all of the responsibilities that come with it?

Life is always a shade of gray.

Further Reading:

Is a Starter Home One of the Worst Purchases You Can Make?

1The S&P 500 is up 9.7% annually or nearly 1600% in total since 1990. Yes, I know the CAPE ratio is not perfect but it does provide some nice long-term context in terms of how to think about market valuations.