After yesterday’s massive 7% down day, the S&P 500 is now within spitting distance of a bear market, down nearly 19% from its all-time high (which wasn’t that long ago). Providing context through something like this is hard because this one feels different.

Oil had its second-worst day ever yesterday. The coronavirus is upending life for people across the globe. There’s a pretty good chance this could throw the U.S. into a recession. The reasons are different every time but the reality is the stock market goes down on occasion and sometimes it goes down a lot.

A reporter reached out yesterday (see here) to see if I had any words of encouragement for young people experiencing a massive sell-off for the first time in their early investing career. I told her they need to get used to it if they plan on stick it out in stocks over the long haul. If you’re 20 or 30 years old, you’ll likely see a dozen or so bear markets throughout your investment lifecycle. So build that hard fact of investing life into your plan. Losses are the one guarantee when investing in risk assets.

Here’s a piece I wrote for Fortune that runs through the historical record of those losses going back over the past 9 decades or so.

*******

The S&P 500 closed at an all-time high of 3,386.15 on February 19, 2020. Just six short trading sessions later, the stock market is in the midst of a 12% drawdown as of the close on Thursday. Monday and Tuesday were the first back-to-back 3% sell-offs for the S&P 500 since August 2015. Thursday was the first down 4% day since February 2018.

Every time stocks fall a little it feels like they’re going to fall a lot. I’m stating the obvious here but you have to go through a minor correction to get to a major 30%-50% bear market. But the minor correction is far more commonplace because most to the time when stocks are down they only fall a little, not crash a lot.

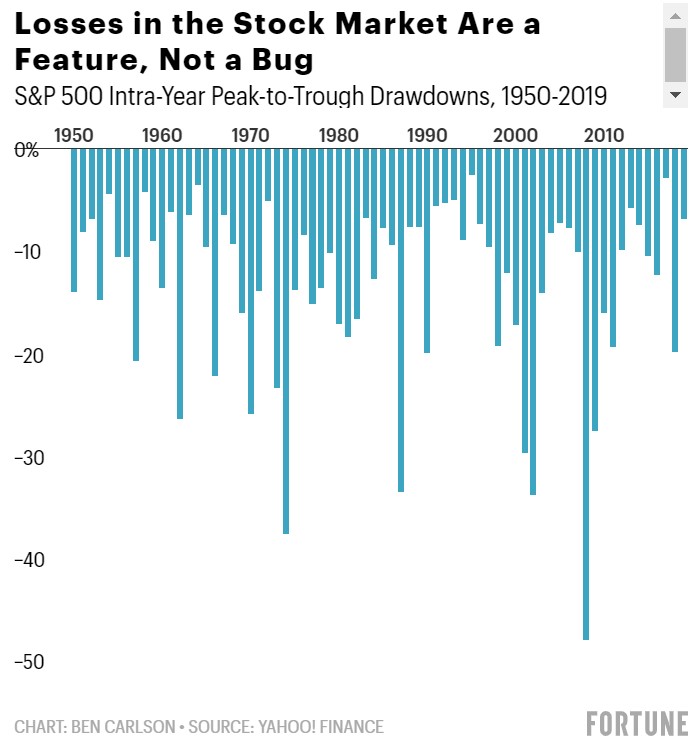

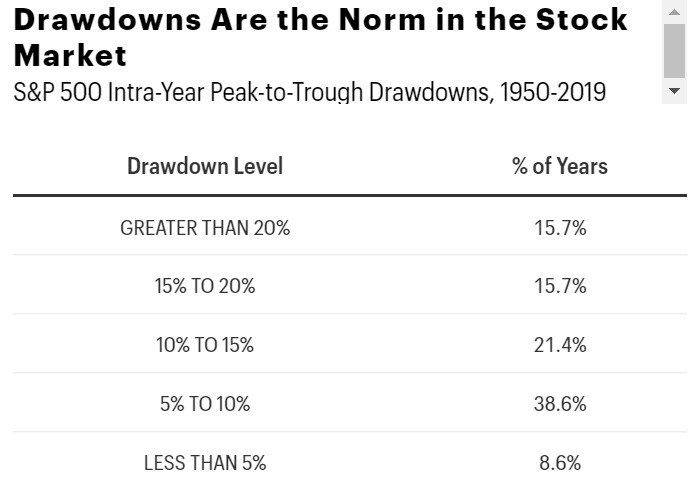

Even when the stock market rises in a given year, it’s not out of the ordinary for stocks to fall along the way to earning those gains. Going back to 1950, the S&P 500 has experienced an average intra-year peak-to-trough drawdown of 13.4%.

So the current pullback is actually right around the average for a given year. Of course, this average result doesn’t tell us what happens every year but downturns are the norm in the stock market.

So roughly 53% of all calendar years for the S&P 500 since 1950 have experienced a double-digit correction. And more than 91% of the time there was at least a 5% correction or worse.

Thirty-seven of the past 70 years have seen an intra-year double-digit correction in the stock market. Surprisingly, 22 out of those 37 years saw stocks finish the year with a positive return overall. And 13 of those years with double-digit corrections saw the S&P finish out the year with double-digit gains.

This means even when stocks have a decent year to the upside, you should plan on experiencing some downside to get there. Years like 2017 and 2019, where the worst drawdowns were -2.8% and -6.8%, respectively, are the outliers not the norm. The market is far more likely to see some serious losses on the way to earning gains than a smooth ride up the entire way.

As an investor, you have to get used to existing in a state of drawdown because that’s where the market is the majority of the time. Since 1928, the S&P 500 has hit new all-time highs in roughly 5% of trading sessions. If we invert this number, that means 95% of the time investors are in a state of drawdown.

This time may feel different because the coronavirus has the potential to wreak havoc on the global economy. No one knows how bad things will get. Volatility begets volatility in the stock market so investors should prepare themselves for more wild swings in price to both the upside and the downside as people work through updates on this outbreak.

But this is nothing new. There has always been volatility in the stock market and there always will be. That’s guaranteed as long as humans are the ones making buy and sell decisions.

In the short-term, the reasons for market sell-offs feel like they matter a lot. In the long-term, investors tend to forget the specific reasons stocks fell in the past.

In the short-term, market downturns feel like they will never end. In the long-term, all corrections look like buying opportunities.

Regardless of how long this correction lasts, to win in the stock market over the long haul you must be willing to lose over the short-term.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.