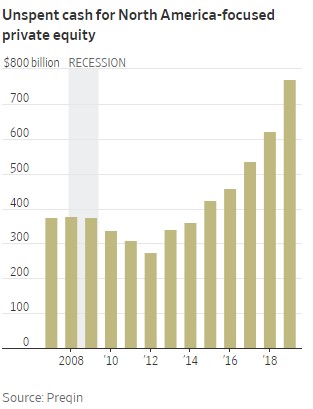

The Wall Street Journal had a piece this past week about cash piling up at private equity firms as valuations in the space continue to rise:

For North American PE firms alone this “dry powder” is fast approaching $800 billion. That’s a lot of cash on the sidelines.

For North American PE firms alone this “dry powder” is fast approaching $800 billion. That’s a lot of cash on the sidelines.

The problem is, this technically isn’t cash on the sidelines because private equity funds work much differently than any other investment vehicle.

At my previous firm we had a substantial allocation to private equity and it was my job to manage the cash flows into and out of those funds. Here’s how I explained this process in Organizational Alpha:

Cash Flow Magnitude Matters. Let’s say your pension fund makes a $10 million commitment to a private equity fund. It’s highly likely that just $6-$7 million of that capital will ever be invested by the private equity fund over the life of the investment period. This is because, on average, private equity funds only call roughly 60 to 70 percent of committed capital. This means that while investors may be receiving decent returns on their private investments, it’s being earned on a smaller capital base than they may realize, thus diminishing the impact of the returns on the overall portfolio.

So that $800 billion of dry powder isn’t sitting in a money market or checking account at all of these private equity firms. It’s sitting in the portfolios of the endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds and wealthy LPs of these PE funds.

Private equity funds don’t invest all of your money the first day you sign up for their fund. They slowly invest the capital over a number of years when opportunities arise. So investors are more or less dollar-cost averaging into the buyout deals the PE firms are executing on their behalf (granted, this is a much riskier style of DCA because it’s typically a concentrated portfolio of private companies).

That money has to come from somewhere in the portfolio.

Many funds equitize their capital commitments and keep some combination of stock ETFs and cash to be ready when those calls come in. That’s exactly what we did at my old fund, selling down the ETF stock holdings when a large capital call came in (they typically give you around a month of lead time to come up with the cash before they’re going to make an investment).

So this dry powder is really just money that’s either sitting in cash or other investments in the portfolios of the LPs who invest in the PE funds. And depending on the size of the deal, those capital calls can sometimes be funded partially or solely from the distributions from current fund holdings that have some sort of liquidity event or dividend payout.

That $800 billion stockpile of commitments isn’t going to rush into the market all at once. It’s going to take time. We often modeled anywhere from 3 to 10 years for a fund to become fully invested. And there were cases where the fund would actually come to the investors and ask for an extension in the investment window they originally promised.

All that money is never always invested at the same time because PE funds make investments at different times, thus making the contributions and distributions of cash flows irregular and impossible to precisely plan for.

Although all the big endowments and foundations we talked to over the years had sophisticated modeling techniques for their cash flows, the actual experience for each individual fund never lined up perfectly with those models.

So like any investment plan, you adjust expectations based on reality.

I’m sure many private equity and distressed investors are hoping for a downturn to allow them to put all this cash to work at lower valuations. This sounds great in theory but doesn’t always work in practice. The financial crisis was a perfect testing ground for this.

During the Great Recession the private equity industry clammed up tighter than Frank Sheeran when asked to rat out the teamsters union. You would have thought the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression would have led to deals galore for private equity. But we basically went through months and months of capital call dry spells.

There are a few reasons for this:

(1) Unless they were in dire straights, most companies didn’t want to sell during the recession because they knew they would have been selling at a huge discount. Few business owners want to sell at the bottom unless they have to.

(2) Private equity portfolios contained plenty of their own companies that were in distress so the majority of the capital calls actually went to shoring up the balance sheets of the current holdings, not new deals.1

(3) Few of the institutional investors in these funds wanted to make private equity contributions because the rest of their portfolios were a mess. They didn’t want to sell down their beaten-down assets to come up with the money for capital calls to make PE investments. And because PE marks their holdings to value, not market, private equity became an outsized allocation in many portfolios so no one wanted to go all-in and screw up their asset allocation even more.

So dry powder in the private equity industry may look crazy big right now. But private equity investments work much differently than other investment structures so all that dry powder doesn’t have the same impact as it would in the public markets.

This stuff will play out over a number of years and won’t have the impact one might expect with other investments.

Further Reading:

Are Private Equity Returns Overstated?

1The secondary PE market was actually more vibrant during the crisis from my perspective because investors in PE funds needed to dump them because their allocations to PE became too large relative to the rest of the portfolio. It wasn’t out of the ordinary to see 50% discounts on these fire sales.