Following the stock market crash of 2007-2009 I witnessed a number of large institutional investors rush out to find strategies that could provide cover from tail risks and offer protection against downside volatility. Most of these strategies were far too complex and expensive to ever work as intended and the results disappointed as these investors were caught fighting the last war.

Decreasing portfolio volatility doesn’t have to be a complex endeavor. Here are some simple ways to potentially decrease the overall volatility of your portfolio from a piece I wrote for Fortune.

*******

Determining how you invest should always begin with an assessment of your risk profile. That’s typically a combination of your time horizon and willingness, ability, and need to take risk in your portfolio. Ability and need require some planning around your goals, current financial circumstances, age, income, family situation and such but these are reasonably easy to figure out.

The hardest part of this equation is determining your willingness to take risk because risk perception is constantly changing with the markets. When markets are doing well, you’ll feel like you should have taken on more risk and when markets are doing poorly, you’ll feel like you should have taken on less risk. And the main determinant of these feelings in almost any investment portfolio will be the stock market since stocks can swing wildly from optimism to pessimism, from booms to busts, and from high levels to low levels.

Therefore, how much money you’re willing to allocate to stocks will have an outsized impact on the volatility of your portfolio. During the Great Financial Crisis, many people realized they couldn’t stomach a market crash, nor the enormous daily swings in volatility cause by owning a portfolio full of equities.

Risk and reward are attached at the hip when it comes to investing but there are ways to curb the volatility of the stock market through intelligent portfolio design, prudent saving habits, and a long-term mindset about the markets.

Don’t get overly complex

Following the stock market crash of 2008, investors dove headfirst into complex hedging strategies such as black swan funds that shine during a market crash or bear market funds that rise when stocks fall. It’s possible you could find success through hedging strategies but they’re often expensive, hard to understand, and difficult to hold for the long-term. The simplest way to lower the volatility of your portfolio is to take less risk by owning more fixed income securities such as bonds.

For example, the S&P 500 was down 56% during the crisis from 2007-2009. A 50/50 portfolio of the S&P 500 and high-quality bonds was down more like 24% in this time. But over the past 10 years the S&P 500 is up roughly 300% while the 50/50 portfolio is up more close to 150%. So taking on less risk lowers your expected downside volatility but also your expected returns. These are the trade-offs.

Taking on less risk can also be accomplished by increasing your savings rate. All else equal, someone who is saving more gives themselves a margin of safety to take less risk in their portfolio so they’re not so reliant on the whims of the markets to build their capital base.

Own uncorrelated assets

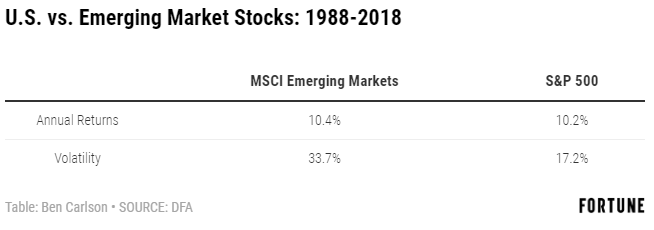

One of the worst parts about investing in emerging markets is the fact that they have bone-crushing volatility. Since 1988, emerging markets and U.S. stocks have similar returns but drastically different volatility:

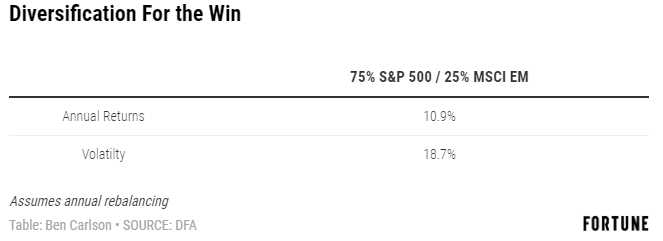

The performance may be similar, but the volatility is nearly double in the developing regions of the world. Since 1994 alone, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has been through 25 double-digit pullbacks while the S&P 500 has seen just 12. This may be too much volatility for some investors to handle but things don’t look nearly as bad when we combine the two using a mix of 75% in the S&P 500 and 25% in the MSCI EM:

By combining two assets that perform differently over the short run, you can see there was a slightly higher return than either of these markets achieved on its own. It is worth pointing out, an investor would have to rebalance into the pain by periodically buying a little of the asset that is lagging and selling a little of the asset that is outperforming to make this relationship work in practice.

Expand your time horizon

If you had bought an S&P 500 index fund the Friday before Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in September 2008, you would be up more than 190% on your money. That’s not bad considering we were entering the eye of the storm for the financial crisis but you would have had to live through a 45% loss over the ensuing 6 months to earn those returns.

Extending your time horizon is one of the best edges an investor can get these days. As you’ll see in the table below, the odds that you’ll have a positive return by investing in the S&P 500 rises to 100% based on historical performance if your time horizon is 20 years. But the shorter your widow, the higher odds you’ll end up with negative performance.

On a daily basis, it’s basically a crap shoot between gains and losses in the stock market. But extending your time horizon can improve your results, assuming you have the requisite intestinal fortitude to hang on or not check your results on a regular basis.

The benefits of not looking at your results very often is also backed by behavioral finance. Loss aversion is the idea that we regret losses twice as much as gains make us feel good. Looking at the stock market on a daily basis means you’ll basically feel terrible every single day, since the pain from loss will outweigh the joy from gains.

By not actively checking your portfolio results you decrease the impact of loss aversion and give yourself a higher probability of sticking with your stocks over a longer time horizon.

This piece was originally published at Fortune. Re-posted here with permission.