Bill Gross had a surprisingly candid interview with Robin Wigglesworth of the Financial Times this week. Multiple times he mentioned his desire for fame as a fund manager:

“I wanted to be famous because I wanted to be loved . . . so I pursued that obsessively,” he reflects at one point. “Shit, that’s why I’m talking to you today.”

Gross attributes his drive to a deep-seated need for recognition. At Pimco he would ask potential hires what they would choose if they could only have one thing: money, power or fame. “I knew for me it was to be famous,” he says. “And I think that people that want to be famous, I think they’re really looking for love.”

“Eventually, as the Coldplay song goes, who would ever want to be king?” he says. His brain might tell him his legacy is intact. “But as you’ve observed, the emotional side of me says ‘people don’t love me anymore’.”

I can’t tell if it’s refreshing or sad that even billionaires who’ve reached the pinnacle of their profession still crave adulation for their accomplishments. I guess money management is always a what-have-you-done-for-me-lately line of business and that becomes ingrained in their thought process.

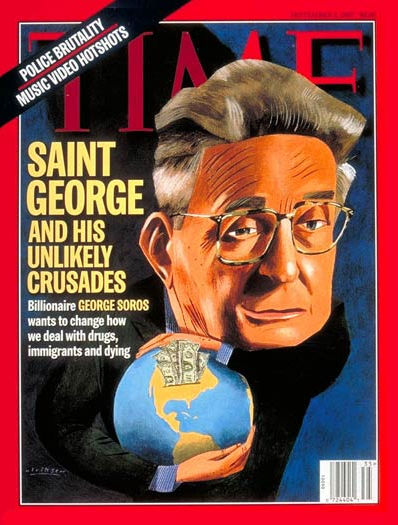

Hedge fund manager George Soros was on the cover of Time Magazine in 1997. The story talked about how Soros actually sought fame just like Gross but for his own reasons:

George Soros became frustrated because his huge wealth seemed to give him no political influence in the West. He realized he needed to become a public personality. In the late summer of 1992, a time of great pressure on European institutions, he did so with a vengeance.

He shorted, betting that the pound would not be able to hold its value against other currencies traded within the Exchange Rate Mechanism.

On Sept. 16, with Soros and others selling pounds, the British government responded by raising interest rates 2 percentage points to attract buyers. By evening sterling had been forced from the ERM. Soros scooped up $1 billion from that escapade and became known all over the world as the Man Who Broke the Bank of England.

‘I had no platform,’ he says today.’So I deliberately [did] the sterling thing to create a platform. Obviously people care about the man who made a lot of money.’

In the 1990s and 2000s, portfolio managers wanted to be stars. They wanted to be adored like Peter Lynch. They wanted nicknames and catchphrases. They wanted to build brands that went above and beyond their firms.

Many still want this but I’m not so sure fund managers should be so thirsty for fame anymore.

Remember John Paulson of the greatest trade ever fame?

He parlayed his amazing subprime trade from the bursting of the real estate bubble into almost $40 billion of investor capital in his fund…which subsequently performed terribly. Earlier this year he decided to shut down the fund and manage his own billions in a family office.

Did anyone that became famous for “calling the crash” come away unscathed on the other side? People raised a lot of money because of that fame but very few money managers who did well in 2008 have experienced similar success in the recovery.

Remember these guys?

Kiss. Of. Death.

It’s not all their fault. The media plays a role in this. Things have changed since the hey-day of the star fund manager in the 1990s. The Internet doesn’t forget and the amount of content being spewed these days is unlike anything well-known fund managers had to deal with in the past.

How much harder is it to think and act for the long-term when your monthly and even daily return numbers become THE story in financial news?

Gross told Wigglesworth, “he ignored the lessons of a lifetime and took excessive risks with his new [Janus] fund.” Part of this stemmed from wanting to prove his old colleagues at Pimco wrong for showing him the door. But I’m guessing it also had to do with the fact that he was clinging to the Bond King title and didn’t want to relinquish the throne to the next in line (Jeff Gundlach).

Famous fund managers also introduce headline risk into the equation. And headline risk can translate into career risk for asset allocators when those headlines are consistently negative.

Index funds and ETFs will never bring you alpha but they also won’t require a board committee meeting to determine why your portfolio manager is in the news yet again for erratic behavior.

Fame can be detrimental to success because it invites ego and as Ryan Holiday pointed out, ego is the enemy.

Maybe the next star fund managers won’t seek the spotlight. Maybe the up-and-coming top performers will keep a lower profile to keep their track record in tack.

Unfortunately, most people who have the drive to become top performers and earn boatloads of money eventually begin to crave something else. Fame is the next logical step once money and power are checked off the list.

So I’m not holding my breath on top fund managers keeping a low profile.

My guess is the lifecycle of those star fund managers will simply be much shorter in the future than it was in the past.

Further Reading:

Why Does Bill Gross Have a Financial Advisor?

Did Bill Gross Tip Over the Pop Machine?