The Fed has raised interest rates nine times since December 2015.

As much as some prognosticators would have you believe the Fed completely manipulates the interest rate markets, they really only have control over short-term rates.

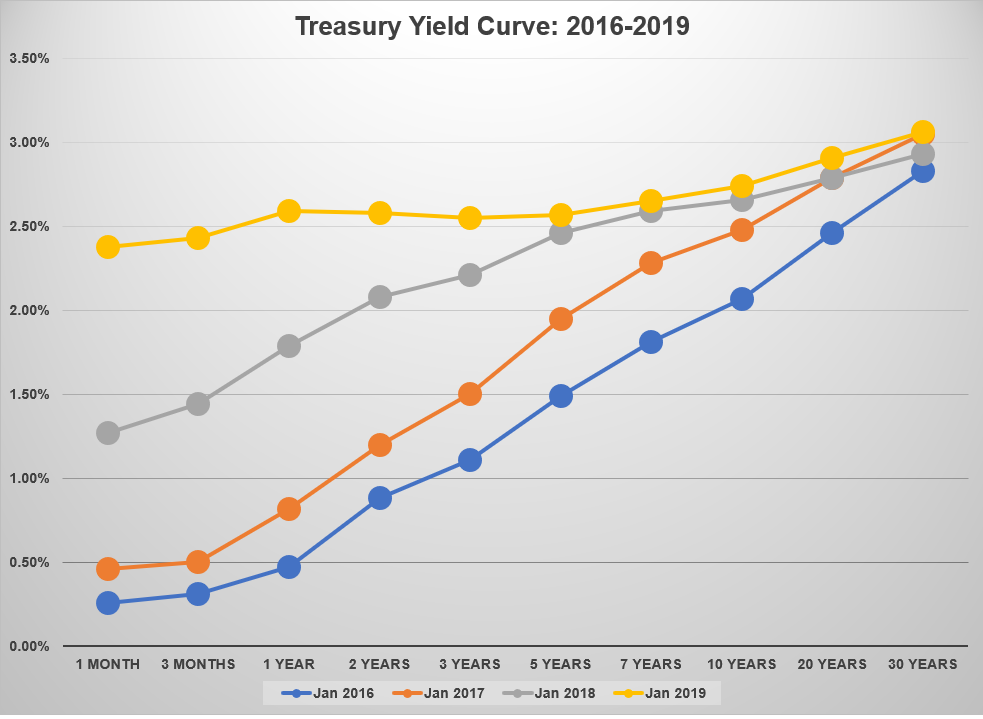

Long-term rates have a mind of their own and the bond market doesn’t always agree with the Fed on these decisions. This idea becomes apparent when viewed through the changing shape of the yield curve these past few years:

You can clearly see the short-end of the maturity spectrum coming up since January 2016 while the long-end hasn’t budged nearly as much. In the case of 30 year treasuries, it really hasn’t moved at all in this time.

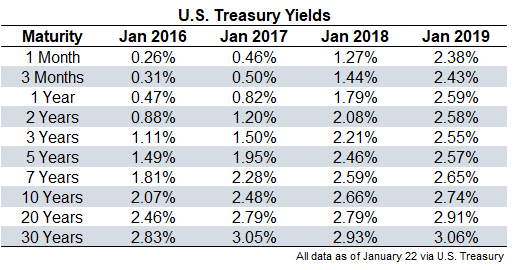

Here’s the rate data behind this graph:

One month t-bills now yield nine times as much as they did in January 2016. Two year treasuries yield almost three times as much as they did in early 2016. But 10, 20, and 30 year yields are only marginally higher in comparison.

In finance textbooks, interest rate moves all occur in the same magnitude at the same time. The real world doesn’t work like that. Different parts of the yield curve move at different magnitudes at different times depending on the market environment. There is no such thing as “all else equal” when it comes to rates be all else is never equal.

These changes have shifted the risk in bond land. When there’s a decent spread between the long and short ends of the curve, investors are being compensated for taking more risk. Volatility increases the further out you go on the maturity spectrum, so it would make sense in a healthy market environment that investors would earn a higher yield for accepting more interest rate risk.

That’s not the case now. We could debate the potential reasons for the fact that the yield curve has flattened out substantially over the past few years, but the reality is the reasons don’t matter all that much. All that matters is how you react to these changes.

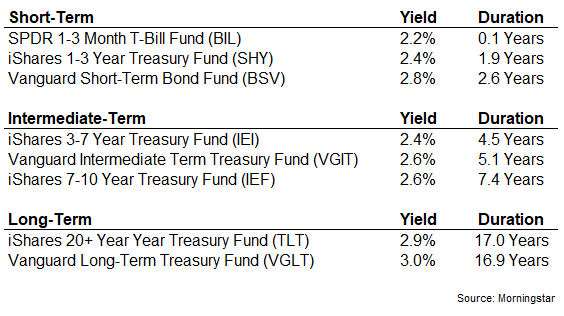

Another way of looking at the current risk set-up in bonds can be viewed through the lens of duration. Here’s a list of various bond ETFs bucketed by their maturity:

Duration is a simple measure of a bond’s relationship to changes in interest rates. All else equal (crap! there it is again) duration tells you how a bond or bond fund will react to a 1% move in interest rates.

So if rates were to rise 1%, you could expect to see SHY fall 2%, VGIT drop 5%, and TLT go down 17% (and vice versa if rates were to fall 1%). All numbers here are approximate because a lot of this has to do with how long it takes rates to rise or fall but you get the point.

So in a rising rate environment, you’re not being paid a premium anymore to extend your maturity in bonds since the interest rate differentials are so slim. However, it should be noted that no one has a clue about the direction of rates so in a situation where rates fall, you would see larger gains on the long end because volatility works in both directions.

My contention is the yield curve is forcing investors to be more thoughtful about their bond holdings in the current environment because rates have come up so much in short duration bonds. A lot of this has to do with what you hope to accomplish by investing in bonds but it’s hard to ignore the relative value in short-term bonds right now.

Regardless of how you position the bond allocation in your portfolio, it’s important to remember that starting yield is by far the best predictor of expected long-term returns. Here’s another chart created by my fellow blogger and colleague Nick Maggiulli which shows the starting yield in 10 year treasuries overlaid with the forward 10 year return:

The correlation is more than 0.9 between starting yields and forward returns.

Interest rates can and will change in the meantime but your starting yield will give you as close to an approximate expected return as anything.1

Further Reading:

The Case For Bonds

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- The art of decision making (New Yorker)

- How to invest for the long-term in a turbulent market (Behavioural Investor)

- Double your money (Reformed Broker)

- Jack Dorsey and Bill Simmons on how to fix social media (Ringer)

- The difficulty of being a bear in a bear market (Inside ETFs)

- The story behind your portfolio (Big Picture)

- Lincoln’s ax and your spending (Simple Dollar)

- The biggest returns (Collaborative Fund)

1This is only true of high-quality bonds such as treasuries. There are other risks to consider in corporates, high yield and other asset-backed fixed income.