Investors often assume the markets are working against them. For those with a large slug of cash to put to work in the markets, the fear is they will put all of their money to work right before the market takes a dive and completely mistime things. There is no perfect time to invest but the lump sum vs. periodic investment decision is never an easy one. This piece I wrote for Bloomberg looks at both the math and psychological forces behind putting your money to work all at once or dollar cost averaging in over time.

*******

The combination of a long bull market, high valuations, rising interest rates and increased volatility can make investors nervous about putting money to work in the market. But many of those sitting on cash missed out on huge gains in stocks.

There are three options for deploying large cash allocations in this type of market:

1. Invest a lump sum and take what the market gives you.

2. Wait for the market to fall further and invest at a better entry point.

3. Dollar cost average into the market to spread your risks.

The second choice always sounds the most appealing to investors, but as the old saying goes, “The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” Holding too much cash can become an addiction for investors who don’t have a plan for deploying capital because bear markets don’t operate on a set schedule. Although the lump-sum option has the highest probability of success, the third option offers the biggest payoff from both a psychological and a market perspective in the current environment.

Research from Vanguard shows that, most of the time, investors would do best by investing a lump sum. The simple explanation is that markets tend to go up roughly three out of every four years. Vanguard looked at a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio in the U.S., U.K. and Australia. It compared the performance of an immediate lump-sum investment over a year against 12 monthly purchases spaced out over the course of a year. The lump sum beat dollar cost averaging about two-thirds of the time. On average, the lump sum beat the dollar cost-averaging strategy by an average of 1.5 percent to 2.4 percent, depending on the country. The results were even more pronounced for longer time horizons.1

But this analysis ignores the market’s current valuation. The S&P 500 stands at the upper end of long-term valuation levels in terms of the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio. The CAPE ratio stands at roughly 32 times the previous 10 years’ average real earnings, a level only reached before the 1929 crash and in the late 1990s when the dot-com bubble popped.

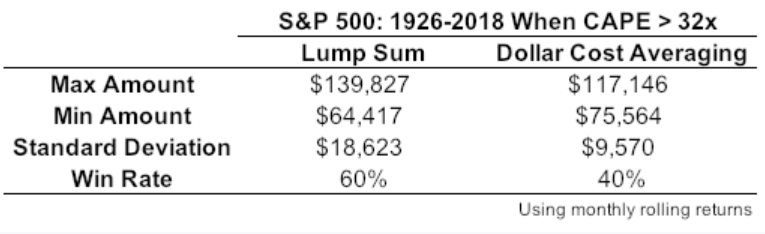

Dollar cost averaging should work better under such scenarios, considering the market experienced enormous crashes in both cases. The win rate falls slightly for the lump sum in these instances, but it still beats the periodic investment approach overall. I compared a lump sum $100,000 investment to 12 equal monthly investments in the S&P 500 over rolling 12-month periods going back to 1926 when the CAPE ratio was at 32 or higher.2 The lump sum still came out ahead 60 percent of the time, but the end values varied much more widely than under the dollar cost-averaging strategy.

These results show that while a lump sum invested at high valuations has shown a higher win rate, this approach has also led to a wider range of outcomes and not always in a good way. The difference between the best and worst-case scenarios when you invested a lump sum was much larger than the dollar cost-averaging strategy. And the volatility of the end results was twice as high.

Under both strategies there were losses in about 40 percent of all 12-month periods, though the losses were much larger under the lump-sum option. The average losses when the ending balance was lower than $100,000 was more than $15,500 or 15.5 percent for the lump-sum strategy. The loss was almost $7,960 using periodic purchases or a loss of less than 8 percent.

Investing is ultimately an exercise in regret minimization. Investors need to ask themselves what they would regret more — missing out on further gains in the market or taking part in large losses? Investing all of your cash at once gives you a higher probability of taking part in larger gains but also taking part in larger losses. To decrease market risk and sleep better at night, dollar cost averaging in a higher valuation environment can lead to a smoother ride and give a lower probability of seeing large losses.

11Over 36-month intervals, the lump sum beat the dollar cost averaging more than 90 percent of the time. The results were much closer over six-month time frames.

2The sample size for this research was 50 rolling 12-month return streams.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2018. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.