Momentum is one of the most misunderstood concepts in the investment world. Everyone intuitively understands value investing (buy a dollar for fifty cents) but few people grasp how much momentum (in both directions) impacts the markets. I wrote the following post for Bloomberg in late-January. Since this was published there have been 13 additional all-time highs in the Dow. This won’t last forever but these things can go on for longer than most would imagine is possible.

*******

Last week, much attention was rightly focused on the Dow Jones Industrial Average as it breached the 20,000 mark for the first time.

In past cycles, such peaks have led to bouts of euphoria as investors had a fear of missing out on further gains. Although a similar feeling could be motivating some investors today, many seem to still be scarred by the two crashes of the past 16 years or so in which the market was cut in half each time.

The thinking is that any time stocks reach a new high it must mean that we are close to a peak that will surely bring the market crashing down. That is always a possibility, of course, but investors in stocks have to remind themselves that they will see many highs in a lifetime of investing. Generally speaking, stocks go up most of the time. A few of those highs will be temporary peaks but most will simply lead to even more highs down the road.

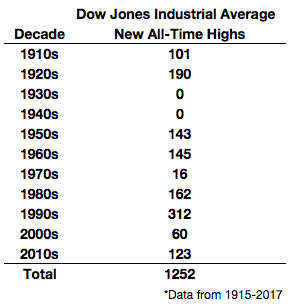

For example, looking at over 100 years of data on the Dow going back to 1915 shows that stocks have had 1,252 highs. That works out to an average of about 12 new highs every year. Assuming the average investor is in the markets for 40 years, that would be almost 500 highs in a lifetime of investing in stocks.

This table shows the number of highs by decade going back to 1915:

There was an enormous dry spell following the Great Depression, but beyond the aftermath of that cataclysmic period, new highs in stocks are perfectly ordinary. Almost five percent of all trading days over this time span have seen new highs.

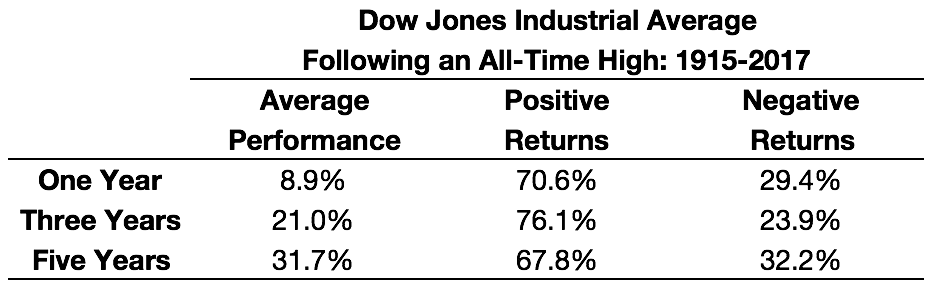

To take this a step further, it can also be useful to look at how well stocks have performed in the ensuing years after reaching highs. This table shows how the Dow has performed one, three and five years after reaching a new high:

The average total returns for one, three and five years are right around the long-term average in the stock market of about 9-10 percent annually over this period. And stock market returns have been positive for most of the time following these events over all three time horizons.

There are some caveats. If five percent of all trading days have led to highs, that means stocks are trading below a high 95 percent of the time. So the majority of the time stocks are in a state of drawdown, which can affect the psyche of any investor who doesn’t understand this fact. Most of your time as a stock market investor is spent in a state of regret.

There’s also a good possibility that when stocks do peak, the downturn could be fairly severe. Since the 1920s, when stocks have been in the most expensive quintile of historical valuations, which is where they are now, the average drawdown when that cycle ends is a loss of 33 percent. When stocks are in the cheapest quintile of historical valuations, the average drawdown is just 6 percent.

Eventually a bear market will be traced back to a peak that came at a high. The problem is that we’ll only know about that peak in hindsight. Most of the time highs lead to more highs. But when the party stops, be aware that the other side of those highs could mean a severe bear market.

Originally published on Bloomberg View in 2017. Reprinted with permission. The opinions expressed are those of the author.