One of the most heavily debated topics in retirement planning is figuring out the safe withdrawal rate. The general rule of thumb is 4% of your portfolio, but if you have the bulk of your assets in tax-deferred accounts such as a 401(k) or IRA, the government makes it easier on retirees to figure out their withdrawal rate once they turn 70 through required minimum distributions (RMD).

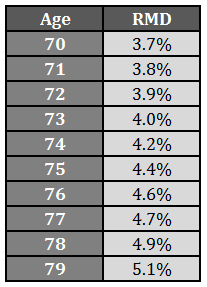

At age 70.5, you have to take distributions from these accounts because the government would like to collect taxes on your gains. Here are the RMD distribution rates by age:

I decided to run some historical scenarios based on a few different asset allocations to see how these rates could be used in concert with a disciplined rebalancing plan. To keep things simple I used the Vanguard three fund portfolio consisting of the Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX), the Total International Stock Market Index Fund (VGSTX) and the Total Bond Market Index Fund (VBMFX).*

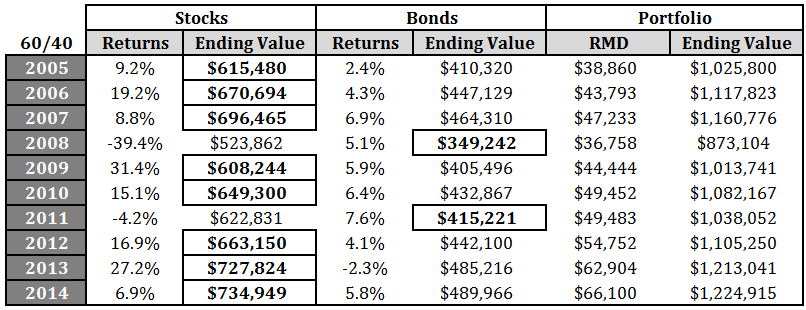

I decided to take distributions from either the stock or bond allocation depending on which one had the better gains each year. There was also am annual rebalance to bring the allocation back in line with target allocations and the RMD was taken out at year end. Let’s see how things would have looked with this strategy over the past decade, starting in 2005 going through the end of 2014 using a $1,000,000 starting portfolio value. Here’s the 60/40 portfolio:

The highlighted ending values show where the RMDs came from each year. You can see that the majority of the distributions were taken from stocks, while bonds picked up in the slack in 2008 and 2011 when stocks fell. Things worked out pretty well with this strategy considering the huge loss in 2008. The balance still grew by over one-fifth even after taking a decade’s worth of distributions.

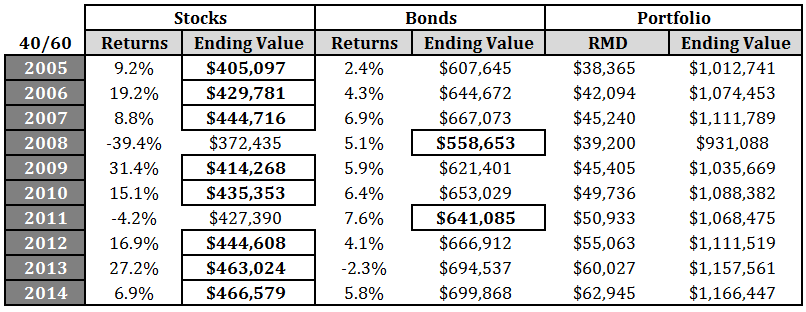

Now let’s look at a more conservative, bond-heavy 40/60 portfolio:

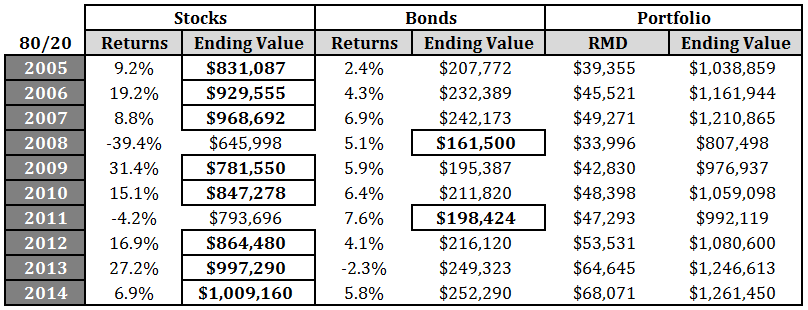

RMDs were taken from the same places, but there were far fewer fluctuations in the portfolio’s value because of the fixed income tilt. On the other end of the risk spectrum, here’s a stock-heavy 80/20 portfolio:

These three scenarios do a great job illustrating the general risk-reward relationship in the markets. All three portfolios took distributions of close to half a million dollars over the 10 year period, but the 80/20 portfolio showed an ending balance of nearly $100,000 higher than the 40/60 portfolio and about $36,000 more than the 60/40 mix.

But the ending balance will always depend on where we’re at in the cycle. The 40/60 portfolio fell just 16% in 2008 while the 80/20 portfolio was down more than 30%. The 60/40 allocation fell 25%. Including the RMDs, here were the annual returns for each portfolio over ten years:

- 80/20 Portfolio: 7.0% per year

- 60/40 Portfolio: 6.7% per year

- 40/60 Portfolio: 6.1% per year

It would be a mistake to make a portfolio asset allocation decision based on the highest ending balance or annual return. Each individual has to figure out how to balance returns with their sanity depending on how much risk they’re willing and able to take. Holding an 80/20 portfolio might work out in the end, but not if you give up on it in 2008 and sell all of your stocks. You’ll notice that the 40/60 portfolio had a balance that was more than $120,000 higher than the 80/20 mix by year-end 2008.

There are a number of other ways to take your retirement distributions, so this is just one example. The rebalancing period could be changed or even where and when you take out the cash. This is simply for illustrative purposes to see how this type of strategy would have worked out over the past decade. As with all strategies, the investor has to go with the one that makes sense for them. You have to be able to follow through on a plan consistently because the future won’t play out exactly like the past.

Further Reading:

The Four Year Rule

Time Horizons & Withdrawal Rates in Retirement

*For the 60/40 portfolio the allocation was 40/20/40, respectively. For the 40/60 and 80/20 portfolios, the U.S./Int’l ratio was kept in the same proportion of 2/3 US and 1/3 international for stock market allocation. The ending value in stocks and bonds are shown after the RMD and annual rebalance. The usual disclaimer applies here — do what works for you and don’t plan on future returns looking like they did over the past ten years. Feel free to let me know if there are any problems with my calculations.

Excellent post. One question: Isn’t the RMD amount based on ending balance of previous year?

Good point. under these assumptions, you could say that you’re taking the RMD at the beginning of the year then and it wouldn’t change anything, but I see your point.

It may have to depend on if you are starting out the withdrawal phase at the beginning of a “bad” decade of returns, as a mediocre decade of returns may be worse than a short term crash event. As it is difficult to assess this, one could look to most conventional “fundamental” valuation measures. Lately, these measures have been pointing to subpar 5 and 10 year forward returns. A sound tactical asset allocation process would help improve the “uncertainty” of the situation, at least for a portion of the assets ….

That’s very possible. I do think it can make sense for investors to diversify not only my asset class, but also by strategy.

Very instructive post. It will be interesting to see any impact of the apparent withdrawal rate changes in the imminent federal budget. It also strikes me that these calculation should be an added value service when one is using an adviser. Sadly, I suspect that is most often not the case.

Thanks. You don’t hear about these things too often, but I have a feeling that’s going to change soon with all of the retiring baby boomes that will have to figure out what to do with their retirement savings.

Ineresting post and comments. Because I use The Four Year Rule method I rebalance using withdrawals from only stock mutual funds as long as we are not in a bear market – a bear market being defined as one that has fallen 20% from whatever the record high has been. Recently I have been withdrawing from my internetional funds because they have been so strong and thus have increased in value over the percent (30%) level I desire. Note — I do not use the four years of cash assets in my calculation of percentages.

Also, most retired folks today have their money in tax-deferred accounts and will most likely have to exceed their RMD levels to meet their monthly expenses. Anyone with high deductions should consider doing conversions to Roths.

I like the idea of using distributions as a natural form of rebalancing from your best performers. It’s a great risk control too. Good thoughts on the tax onsiderations as well. That’s not something that should be ignored.

I think the RMD method of retirement withdrawal, while financially sound, is very flawed in that it increases withdrawal amounts from age 70 to age 80, whereas published studies have shown that actual spending declines from age 70 to age 80. This means that one gets less money when younger, which is when one is more likely to want and be able to enjoy having it. Following the RMD withdrawal method can therefore result in an unnecessary decreased quality of life. There are several other methods (such as the 4% rule) that avoid this problem. After all, the whole point of saving for a secure retirement is to be able to maximally enjoy retirement!

True, but remember this is just the minimum amount. People can still take out more than this if they are so inclined, but I do see what you mean about structuring the distributions for maximum pleasure. The good thing is that you can continue to allow your funds to grow tax free for longer and use taxable accounts to make up for the shortfall if need be.

And a 100/0 allocation would have been best of all allocation over that 10 year period even though it contained the worst recession in 80 years, a 55% drawdown in the S&P 500 from Oct 2007 to March 2009, and the biggest bond bull market in history. Wow.

With the 80/20 and 60/40, the investor ends up with a greater balance at the end and got more in RMD’s than she would have with the 40/60. This is excellent proof that volatility does not equal loss in any form or fashion.

Very true. Others have asked my how something like this would have done in a sideways type of market like the 1970s but even in volatile periods you still get many chances to rebalance. The only problem with the 100/0 is that you’d be selling stocks after a huge drawdown to take that distribution because you don’t have the bond or cash buffer.

[…] “Rebalancing with Mininimum Distributions” from Ben Carlson (@awealthofcs) https://awealthofcommonsense.com/rebalancing-with-required-minimum-distributions/ […]

[…] Portfolio rebalancing with required minimum distributions. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] Reading: Rebalancing With Required Minimum Distributions Time Horizons & Withdrawal Rates in […]