The Wall Street Journal shared the results of a survey which shows many investors don’t understand how bond math works:

Despite the massive growth of the bond market in recent years, many individual investors are still fuzzy on their bond math.

A recent survey conducted for BNY Mellon Investment Management found that 40% of individual investors don’t know bond prices fall when interest rates rise, and vice versa. It’s a central tenet of bond investing that helps explain why everyone in the bond world is so focused on when and by how much central banks like the Federal Reserve adjust benchmark interest rates.

Bonds are much more formulaic than stocks. Long-term returns tend to track the beginning interest rate. When rates rise, the price of a bond falls. When rates fall, the price of a bond rises. There are some minor intricacies including convexity that come into play, but for the most part bonds and rates have a simple inverse relationship.

Here’s an example. Let’s say the current market interest rate is 5% and that’s the yield on the bonds you hold. Then the market rates go up to 7% so new bonds now pay that higher yield. But you’re still holding a bond that only pays 5% so no one is going pay you 100 cents on the dollar for it when they can earn 2% more with a newer security. The price of existing bonds has to fall to bring them in line with the overall yield of the now higher-yielding market interest rates. When rates fall your bond is worth more because market yields are lower than the bond you hold.

Even those investors who do understand bond math often misinterpret what this really means since this is from the standpoint of prices and principal value. It doesn’t consider total return. Yes, if interest rates rise a substantial amount in a short period of time investors will see losses in their bond holdings. But these losses are temporary when we’re dealing with high quality bonds. And rising interest rates doesn’t have to lead to losses in bonds. It all depends on the starting yield and the magnitude of the rate rise.

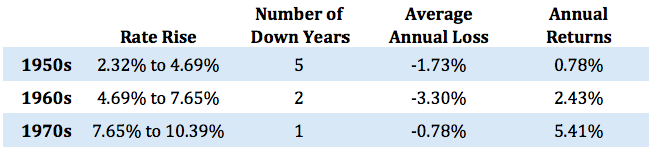

My favorite example of this is the rising rate period from 1950-1981. Rates went from 2.32% all the way up to 15.32% on the 10 Year Treasury. Returns, however, were not as bad as you would think:

Rates went sky high but returns were still positive every single decade. They weren’t great, but they were still positive from a nominal perspective. It was only after accounting for inflation that bonds showed real losses in this time and most of that was from the 1970s.

The 1950s scenario makes the most sense if you’re looking for a parallel to today’s markets. Interest rates doubled over the course of the decade and 10 Year Treasury returns were down every other year. Those losses were fairly subdued (-0.30%, -1.34%, -2.26%, -2.10% and -2.65%) as a bad year in the bond market is like a bad day in the stock market.

This is one of the reasons that average investors (and let’s be real, many professionals) are so confused about the mechanics of bonds. Yes, rising interest rates means lower bond prices. But it doesn’t necessarily mean lower bond total returns. Remember, to earn better long-term returns in bonds we need to see higher interest rates eventually. When yields rise you start to earn more income. That’s a good thing.

Of course, investors have been nervous about rising rates for some time now and it just hasn’t happened. Even after the Fed raised the Fed Funds Rate in mid-December, market interest rates have continued to fall. Who knows when rates will rise. When they do, investors have to remember that there will likely be some short-term losses. But bonds still pay out their income and mature at par value. From a total return perspective this means it won’t be as bad as some would have you believe (as long as we don’t see negative rates).

Source:

Many Investors Are Still in the Dark About Bonds (WSJ)

Further Reading:

The Most Interesting Asset Class Over the Next Decade

All good points. And of course, some investors have bonds paying 7% coupons today that are priced at $115 and they’re so excited. But they don’t realize that bond is going to approach $100 as it nears maturity and that the 7% coupon feels good, but really a yield to call (YTC) or yield to worst (YTW) value is more likely what the return will be on the bond over time.

And of course, credit ratings and all that come into play… (maybe another blog post!)

yup many different risks to consider in bonds beyond interest rates – duration, credit, inflation, etc

Does similar math hold true for bond mutual funds?

Owning an individual bond is very different than a bond fund. The total return on the bond fund is going to depend on reinvestment rates, time held, maturity of bonds, etc. There’s a lot to consider with how a bond fund is run versus some of the math that you can figure out with just a single holding.

see here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/misconceptions-about-individual-bonds-vs-bond-funds/

Does the same logic apply to buying into a bond ETF? Bond ETFs hold bonds with several different maturities if I’m not mistaken. Do current rates matter when buying one?

see here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/misconceptions-about-individual-bonds-vs-bond-funds/

The last sentence of your blog is a teaser to me. If you deem it worthwhile, I’d be interested in your thoughts on how negative interest rates would affect the various components of a typical diversified (by maturities and qualities) bond and bond fund portfolio.

I hope it never comes to that because that would mean something is very wrong with the world but I think at that point you’d have to take a hard look at cash or go further out on the risk curve beyond the highest quality bonds

As a retiree, I fear my chronological time to recover from a protracted downturn in financial assets is limited. Even with a couple decade horizon, I am uneasy NOT holding a significant portion of my fixed income assets in money market and very ST bond funds. It’s my understanding that some of the debt of two major developed world economies (Japan and Germany) are already currently priced at slightly negative rates of yield. And didn’t Ben Bernanke recently say in an interview that negative interest rates were a real (versus just hypothetical) possibility?

Despite the preceding, I understand the lesson of “stay the course,” albeit perhaps easier to execute in the asset accumulation phase of life. I hope my anxiety is overblown and, at worst, I am being too cautious with my fixed income portfolio, but I have had a longstanding discomfort with how the global financial world has strangely and unpredictably acted in this “New Normal” environment since 2008.

I wish I shared your hope!

A possible alternative strategy http://www.aarp.org/money/investing/info-2015/long-term-investment-savings.html

I hadn’t considered that. Thanks!

That was an excellent explanation – I finally now understand bond prices and yields

Two more important factors- 1) a lot depends on the forward interest rate that are priced into the bonds at a certain point in time and 2) in a rising interest rate environment, whether the bond coupons are actually reinvested at the higher interest rates

Here in Canada we have had the ‘experts’ ALL making that false claim for the past year. They have been claiming that our RateReset preferred shares have dropped 20% in price “because interest rates have fallen”. Totally bogus. Prices have dropped because the risk premium has risen by 1- 2- 3 percentage points – along with other debt.

And no the concept of ‘negative duration’ is not their excuse. These securities benchmark against the same 5-yr Treasury that determines their distributions.

Retail investors cannot be expected to get this right, when told otherwise by the experts.