Morningstar’s Jeffrey Ptak posted some insightful data on Twitter over the long holiday weekend. Take a look at these 10 year performance numbers for actively managed mutual funds once you account for the effects of taxes on investment returns:

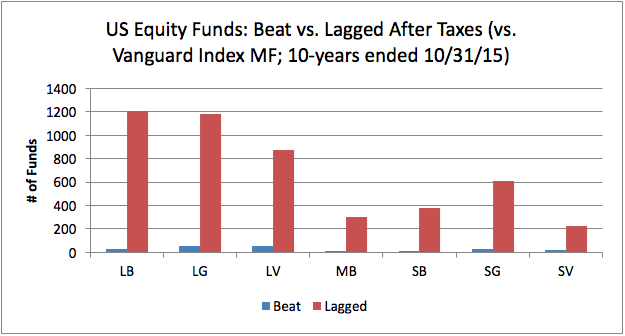

This shows the number of funds in the various U.S. equity mutual fund groups — large blend, large growth, large value, mid blend, small blend, small growth, small value — that beat their respective Vanguard fund benchmarks over a ten year period after accounting for the tax bill. Those tiny blue lines are the number of funds that won out. Out of nearly 5,000 funds in total, just over 200 actively managed funds beat the Vanguard funds after tax.

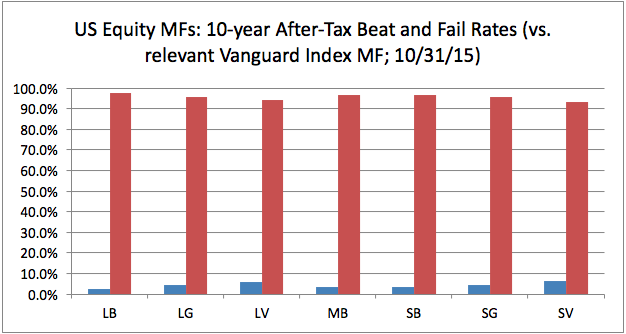

To really drive home the point, here are the number that beat the Vanguard funds broken out as a percentage of the total for each:

The average number of actively managed funds that beat their Vanguard counterpart was just 4.3%! I had never seen the data presented this way so I reached out to Jeff to see if he would send me his data (See below for some notes from Jeff if you’re interested in his methodology here). He actually told me that the active performance would have been even worse than this because many of the funds that beat the Vanguard funds were themselves index funds from other fund providers.

By now everyone in the industry is well aware that the majority of actively managed mutual funds fail to beat their benchmark over time. Many people point out that one of the main reasons for this is because of the high costs seen in many active funds. But taxes and trading commissions can also completely destroy even the best performance from a portfolio manager.

A few other takeaways from this data:

- Tax location is an extremely important aspect of a comprehensive financial plan. If you plan on holding a number of actively managed funds, it’s best to do so in a tax-sheltered account. As these numbers show, it simply doesn’t make sense to try to compete with Vanguard on an after-tax basis.

- High turnover can be a killer to fund returns. Value investor Monish Pabrai once said that, “money is made not in the buying or selling but in the waiting.” Most professional investors don’t have the patience or required time frame to wait so they overtrade and make constant changes to their portfolios. This leads to higher trading commissions, market impact costs and a large capital gains distribution for their taxable investors. It’s amazing how much of an advantage you can gain when you have a longer time horizon to invest.

- It seems that very few portfolio managers care about the returns their investors actually receive. Obviously, investors have to take some responsibility for their own buy and sell decisions, but I’m not sure many retail clients understand the tax implications of the strategies they employ in their portfolios.

- I’m continually shocked that more actively managed mutual fund firms aren’t making a huge push into ETFs. ETFs would mitigate much of this tax disadvantage. Yes, the fees would have to come down, but I would imagine there is going to be a first-mover advantage for those enterprising firms that make the leap into this space. It makes absolutely no sense to saddle your investors with huge tax bills year after year.

- As I’ve stated in the past, index funds are nothing special. They’re low cost, low turnover, regularly rebalanced and rules-based. There is no reason that actively managed funds can’t do these same things (and to be fair, some are now doing this but not nearly as many as I would like to see).

There’s an old saying in the investment business that you should never make an investment decision based strictly on the tax implications. There may be some truth to that, but this data shows that you can’t underestimate the effects that taxes can have on your net portfolio returns.

Make sure to follow Jeff on Twitter: @syouth1

Further Reading:

The Opportunity in Active ETFs

Methodology:

Scope: US equity funds, oldest-shareclass only, includes ‘obsolete’ funds. Obsolete funds were treated as ‘laggards’ for purposes of this analysis; to ‘beat’, a fund must at least survive the full period.

I sought to understand how many of the funds classified in a particular category at the beginning of the year went on to beat a relevant index fund after-tax over the ensuing 10-year period. That explains why you see the category classifications as of October 2005.

I used Vanguard index funds, where available, as the ‘relevant index fund’ for each category. For mid-growth and mid-value, no such Vanguard fund existed as of October 2005 so I’ve scoped those categories out of the study.

The Vanguard index funds are measured in the same way as the active funds, using ‘post-tax’ return methodology. This datapoint considers not just ‘internal’ tax-efficiency of the fund (i.e., mix of ordinary income and cap gains; unrealized cap gains vs. CGs distributed; qualifying income vs non-qualifying; etc.), but also assumes the investor sells at the end of the period. It’s sometimes referred to as the ‘post-liquidation’ after-tax return, whereas the ‘pre-liquidation’ figure does not assume the investor sells at the end of the period.

Per the SEC’s calculation methodology for after-tax returns, the returns are load-adjusted, something which is load-fund unfriendly. However, because I chose a longer time period, this should help the front-load funds (which are typically the ‘oldest shareclass’ designated) work off their load and not depress the after-tax returns to a punitive extent.

More and more, I liken most active management to gambling: the thrill of possibly getting lucky is just too tempting for many investors!

Might as well go to a casino, you get better odds there and there are free drinks. 🙂

While I sympathize with the comments above, and I’m sure they were made tongue-in-cheek, I think it’s important to be clear that even an active fund that fails to beat the benchmark is still typically far superior to a casino in too many ways to list them all, even if the fund manager is trigger-happy. Too many people discount the idea of investing anything at all in the market, and justify it by labeling it ‘gambling’. However, a fund of significant size has so many securities, the manager is bound to get lucky with a few of them, and yield a positive return more often than not, even if it lags. Mean reversion tends to save the day.

I was kidding… but most active funds don’t beat their own benchmarks! So while better than the casino, in the sense that the casino is negative expected value, it’s not better than index funds.

Absolutely! Didn’t mean to be pedantic, and it’s true some people invest as if they were in Las Vegas – like the guy who recently lost $143k on a short gone bad when the stock went up 800%. I think the market is a true friend when it comes to building wealth, however, as long as it is treated with the proper caution. Did you see Ben’s recent (& awesome) post on compounded returns? It so beautifully demonstrates the power of staying invested! As for active funds, I do have 10% of my portfolio in one that I like, but 90% is index funds – it’s a better value and offers much greater accuracy in matching my desired asset allocations.

That short makes me feel badly for the guy but not that badly, we’re all adults here and are capable of making our own (horribly horribly bad) decisions. 🙂

I think anyone who’s invested for any length of time can identify with that sentiment! The story was on CNN Money, and the comment section lays out his mistakes. I admit feeling both ways about it myself, but it makes me think of Buffett’s first rule, don’t lose money. I question the idea from a literal standpoint (incorporating the idea of price vs value – I would assert that Mr Buffet loses money with reasonable frequency, but the value of his investments usually trend positively regardless of the price Mr Market puts on them.)

Of course he loses money, but when you look at the deals he makes they’re all in his favor because of his access to capital.

Another Buffett-ism is to only invest in things you understand. Clearly that guy didn’t understand 1) his investment 2) shorting and the risks involved. A one-two punch that will likely KO him for a while.

[…] Why tax location is so important. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] of the Gold Standard? Not Really, Historians Say (NYT) • Uncle Sam Loves Active Mutual Funds (A Wealth of Common Sense) • Credit-Card Rules Have Cut $16 Billion in Fees: Report (WSJ) • Cultural “fact […]

[…] in the year. We were sold these funds years ago as sold by our former financial advisor. (If you don’t understand why you don’t want to hold actively managed funds in a taxable a…) Thus we saved ourselves about $2,000 in taxes for taking less than 30 minutes to analyze the […]

[…] investors, and a complete disaster if used in taxable accounts. Ben’s article can be found here. The chart below is the lead graphic and paints an ugly picture for active […]

[…] Ben Carlson posted an article on his great blog, A Wealth of Common Sense, using data published by Jeff. Its titled “Uncle Sam Loves Actively Managed Mutual Funds” and can be found here. […]

[…] Tax alpha. Most investors don’t spend enough time worrying about Uncle Sam’s cut of their profits and that’s a mistake. Taxes matter much more than alpha to the taxable […]

[…] Uncle Sam Loves Active Mutual Funds […]