One of the common misconceptions I’m starting to hear from investors is that because we’re in a low interest rate environment, stocks either can’t or won’t fall very far from these levels. This is the TINA (there is no alternative) argument that says because over the longer-term bonds returns will be much lower from today’s yield levels, stocks should be supported because people have to put their money to work somewhere to earn a respectable return.

This theory does make a lot of sense when coming up with an explanation as to why the market has always seemed to have a bid under it anytime stocks started to fall over the past few years. But it would be a mistake to assume that this can go on forever and that risk won’t rear it’s ugly head eventually with another bear market.

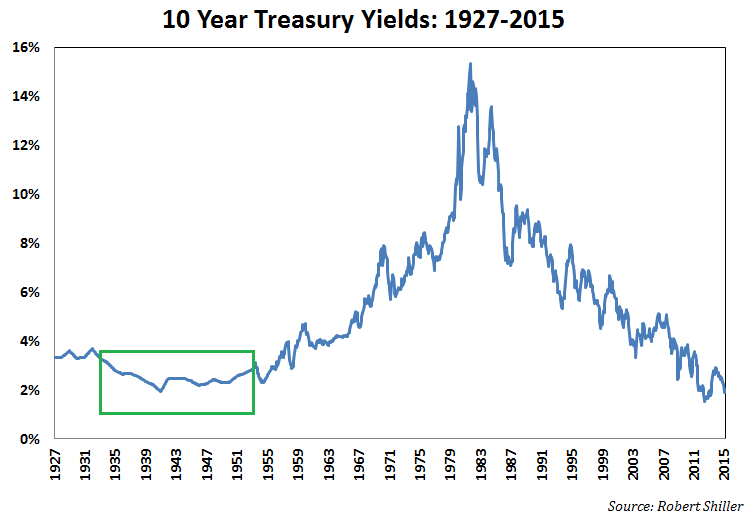

The 10 year treasury yield dropped below 3% in late-2011 and although it briefly hit that level for a couple days in late-2013, rates have continued to stay low. There is a historical precedent for low interest rates that we can use for comparison purposes here. In June of 1934 the 10 year treasury yield dipped below 3%. It didn’t go back above 3% again until May of 1953, almost twenty years later, as you can see from the highlighted section of this long-term chart:

As you would expect from the low starting yield levels, bonds performance was underwhelming, with an annual return of just under 3% nominal or a loss of nearly 1% annually after inflation is taken into account.

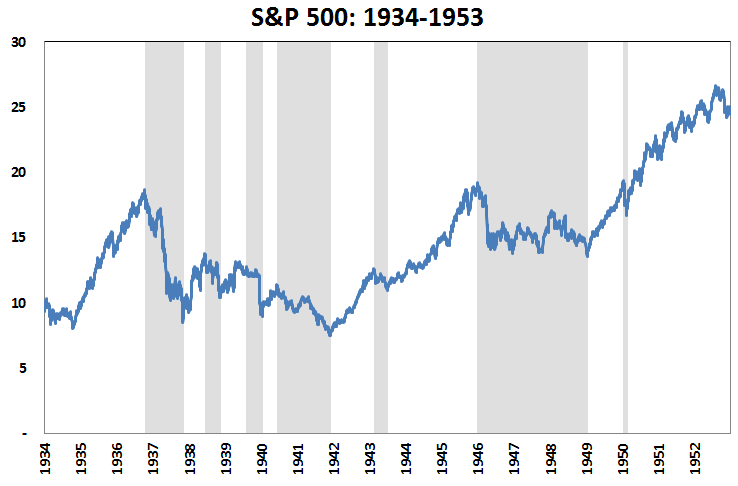

Although rates were so low, setting up a possible TINA market back then, stocks were extremely volatile during this period. Each of the highlighted sections in this chart of the S&P 500 corresponds to a double digit loss:

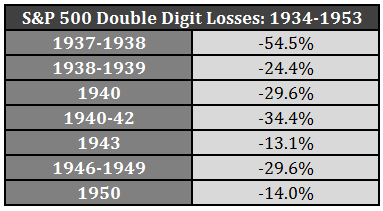

I counted seven different occasions where there were double digit drawdowns over this nearly twenty year period (and it could have been more had I counted the many stops and starts during the 1946-1949 drawdown). Here are each of those double digit losses, which included five separate bear markets:

With all of these losses you would think investors couldn’t have possibly fared too well over the entire period. Yet with dividends reinvested, the S&P 500 was up a total of more than 600% which works out to annual returns of 10.9% per year. This despite the fact that investors had to endure the market getting chopped in half once and falling by a third on three separate occasions. There was a market crash every four years or so, but stocks still provided above average double digit annual gains.

It’s also worth noting that these returns were heavily back-loaded. For the first eight years the S&P was only up 2.7% per year. It was the following twelve year stretch that saw 15.2% annual returns to make the entire period look like a smashing success.

I’m not saying this is what’s going to happen from here. Interest rates are just one variable. You can’t look at the markets in a vacuum to discern what’s going to happen next based on what’s happened in the past. This period started out just after the depths of the Great Depression. While the Great Recession was severe, it’s was nothing compared to what was experienced back then. But there are a few takeaways from this data that I think investors should consider:

- Just because interest rates are low doesn’t mean stocks can’t or won’t fall. Interest rates are a very important factor in the markets but they’re not everything.

- Stocks are risky. To make money you have to be willing to accept occasional losses. Get used to it if you’re invested in risky assets.

- Even in a volatile market environment laced with bear markets, stocks can still make money for patient investors.

This past week I made the comment that true long-term investors root for market crashes or bear markets to buy stocks at lower prices while charlatans root for a crash so they can say they were right. Remember this the next time a bear market hits. Also remember no one know when the next one is coming.

Further Reading:

What Happens to Stocks & Bonds When the Fed Raises Rates

Market Returns During Ray Dalio’s 1937 Scenario

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Excellent, I would also add that this happened in Japan. Rates have been low and equities there have been volatile and have experienced losses as well. In addition many people say, that the equity markets detect weakness in earning because of deflation which is often reflected in low rates. Last but not least, the FED eased all the way through 07-09 and 2000-2003, so low interest rates are no panacea.

Good points. Japan has been a tough nut to crack. It’s not only interest rates that matter, but the expectations baked into them, something not many people are good at figuring out.

[…] Stocks can absolutely fall with ultra low interest rates (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

“Yet with dividends reinvested, the S&P 500 was up a total of more than 600% which works out to annual returns of 10.9% per year”

I have to disagree with your above statement. During the time period in question, 1934-1953, there was no practical manner for any investor to buy the entire S&P index and benefit from dividends; thus your conclusion is only theoretical (as are all pre-index fund returns).

It would be great if actual account data was available to study, but I’ll guess most stock investors did not see a 600% increase in their accounts.

In fact, the S&P 500 index was launched in March 1957. Before then, S&P’s daily market index was the S&P 90, consisting of 50 Industrials, 20 Transports, and 20 Utilities. Institutional investors would have had little difficulty amassing this portfolio.

Practically speaking, before Harry Markowitz provided the theoretical foundation for index investing in the 1950s, everyone was an active investor. According to Richard Ferri, there were 19 open-ended mutual funds in 1929. So some actual portfolio results are available from the period.

Good point. Something many investors don’t even realize. More good tidbits on the history of the S&P 500 here:

http://www.cftech.com/BrainBank/FINANCE/SandP500Hist.html

Ferri (in his book, The Power of Passive Investing) went on to cite Jack Bogle’s 1951 economics thesis at Princeton. Bogle found that during 1929-1936, the average NAV of 49 open-ended mutual funds increased by 6.7 percent. The S&P 90 rose 7.4 percent.

It’s also hard to comprehend what the fees were that investors paid back then. Commissions were enormous. Investors have it pretty good today with how easy everything is. Could also be one of the many reasons that it’s possible returns should be lower going forward than they’ve been historically.

That’s an interesting comment. Makes one think that perhaps there is a natural threshold or ceiling for retail investment returns.

Agreed that historical pre-index fund data should be used only as a general guide.

Could be. I might have to write a piece on this because it’s something I’ve been thinking about lately. The good news is that it’s now easier than ever to get as close to market returns as possible from low-cost ETFs. It’s up to investor behavior to see that it actually happens.

Mandatory stock purchase broker commissions ran in the 8% range until the 80’s…

Of course. This also doesn’t include taxes, fees or commissions paid. It’s quite rare for investors of today to get the S&P’s return because of these factors and poor behavior. Historical return figures are best used to proved context on possible risks, not to show how investors would have fared exactly.

[…] 1) Stock Market Losses With Low Interest Rates by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] 1) Stock Market Losses With Low Interest Rates by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] 1) Stock Market Losses With Low Interest Rates by Ben Carlson via Wealth Of Common Sense […]

[…] There was some good discussion on my post from last week about the return numbers on the S&P 500 from 1934-1953 (see Stock Market Losses With Low Interest Rates). […]