“Shoot the hostage.” – Keanu Reeves, Speed

Speed is one of the definitive movies of the 1990s in my mind. Starring Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock, the movie is full of cheesy one-liners, tons of action sequences, things blowing up before special effects were any good and of course, a deadline. The deadline or countdown of a bomb going off was a staple of 90s movies.

The main plot, for anyone that hasn’t watched this classic, is that Dennis Hopper’s character set up a bomb on a bus to blow up if the speedometer fell below 50 MPH. Bullock drives the bus while Keanu has to save the day.

Many investors and financial commentators treat the markets much like the bus in Speed.

This is the line in the sand. The market better hold here or it’s over. If interest rates fall below this level it spells trouble for sure. This stock is the tell for the entire market. At these valuation levels…

Adam Grimes discussed this in a recent blog post:

Everyone does it. I used to do it too, but I stopped because I realized I looked silly a few months down the road. You’ve heard the predictions: “if this level breaks, it’s game over”, “if the 200 day breaks, it’s the end”, “we just broke the neckline of the head and shoulders pattern. This is the end of the trend”, “the 38.1966% retracement has to hold”, “when the Fed backs off, there’s no way the market can keep going up”, and on and on and on. It seems that everyone has a reason; everyone has some line in the sand, that, if crossed, will spell the end of some trend and a reliable reversal will follow. The only problem is, markets don’t work like that.

Grimes is right, of course. The markets aren’t run by an if/then simulator. Everything is subject to change. And it’s not only true of short-term relationships. There can be long-term regime changes as well.

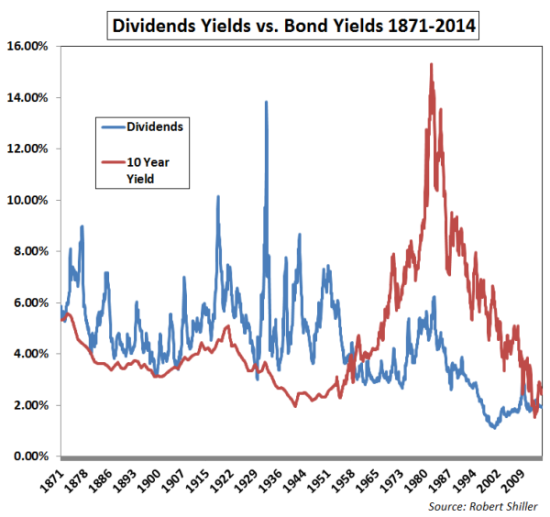

Way back when, companies used to have to pay very high dividend yields to attract equity investors because of the high yields offered on bonds. For nearly 100 years stocks yielded more than bonds, with a few exceptions for very short periods of time. Many investors were under the impression that stocks always had to yield more than bonds and could use the narrowing of the spread as a buy signal. Which worked until it didn’t, as bond yields exploded from the 1960s on.

It wasn’t until recently that stocks once again yielded more than bonds. Here are the dividend yields on the S&P 500 set against the 10 year treasury yield going back to the late-1800s:

William Bernstein touched on some of these changing relationships in his book, Rational Expectations. Staying with the dividend theme, in the past there used to be a strong sell signal whenever dividend yields dropped below 3%. Then a funny thing happened in the mid-90s — it stopped working. It was no longer as much of an issue if the dividend yield dropped below 3%, mainly because of the fact that more companies were using share buybacks in lieu of dividends.

It’s also possible that many signals look great using past data, but would have been impossible to pull off in real-time. Here’s Bernstein with more:

A comprehensive study of the problem of “nonstationary-ness” was recently made by Welch and Goyal, who looked at multiple valuation and macroeconomic variables and concluded that none were stationary enough to be of any practical use, saying, “These [valuation and economic metrics] would not have helped any investor with access only to available information to profitably time the market.”

That’s the problem with much of the historical market timing data people use. While it looks great on paper, it was probably impossible to pull off at the time because of limited information.

And wouldn’t you know, the best time to pick the tops and bottoms is after the fact:

In the 2013 yearbook, DMS echoed Welch and Goyal by pointing out that market observers frequently fall victim to “the gambler’s fallacy,” which in terms of forecasting boils down to this: if you look back on x years of market data, at market peaks, valuations are maximal; and at bottoms, they are minimal. Almost by definition, returns following these are minimal and maximal, respectively. In other words, after the fact, valuation metrics always look highly predictive.

I love Bernstein’s straight forward approach to the markets. His point is that market timing will always look easy with the benefit of hindsight. Maybe past signals will work, but chances are slim that the same market timing buy and sell indicators that worked in the past will continue to work as well in the future.

There are no absolutes in terms of always or never in the markets. The best you can do with historical information is use it to manage risk. It’s never going to give you a screaming buy or screaming sell signal that you can use with any regularity. The best investors use a probabilistic framework, not one that relies on certainty.

In fact, that’s probably the best use of market data, setting reasonable expectations to manage portfolio risk. Past data is never going to make it easy for you.

Even Keanu Reeves understands this point. When they made Speed 2 with the same plot but on a cruise ship, Reeves made a wise decision and passed on the role. The sequel didn’t perform nearly as well as the original and ended up bombing at the theaters.

Sources:

The line in the sand (Adam Grimes)

Rational Expectations: Asset Allocation for Investing Adults

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Ben,

Great stuff. Couldn’t agree more.

“There are no absolutes in terms of always or never in the markets.”

This is exactly why I don’t time the market. I believe time in the market matters a lot more than timing the market. I remember coming across data somewhere that showed even if you would have bought AMEX just before its big salad oil fiasco you and Buffett would have had similar returns from then until now.

I don’t focus on the broader market at all. I focus on individual high-quality companies. I like to bet when the long-term odds are on my side. It’s hard enough to reasonably value one company, which is why it’s completely impossible to value hundreds of stocks all at once (the S&P 500 index).

Best wishes!

That’s an interesting one about Buffett. I’ve never heard that one before. I would say that valuing an individual company is no easier than valuing the market in many ways. In both instances, though, extending your time horizon and not jumping in and out all the time is one of the best ways to increase your probability for success.

[…] Pop Quiz Hot Shot by Carlson […]