In nearly every heist movie from the 80s and 90s, the bad guys would always talk about stealing enough money to find a place on the beach and live off the interest. Here’s a classic from Hans Gruber in Die Hard (h/t Meb Faber):

“Sitting on a beach, earning 20%” isn’t going to happen these days (Die Hard was filmed in the late-1980s), given the paltry yields in government bonds around the globe:

But there are still investors out there who have ‘won the game’ and retired with a large enough nest egg that they don’t see the need to invest outside of bonds. Many are still too shell-shocked from the Great Recession or think stocks are overvalued and want nothing to do with the stock market. I’ve talked to a few people over the past couple of years who say they keep all of their money in bonds because they provide more safety than stocks.

In some respects, I understand this line of thinking. Why continue to play the game when you’ve already won and have built a substantial portfolio? The transition from wealth accumulation to wealth preservation requires a change in mindset, but as with most things can be taken too far.

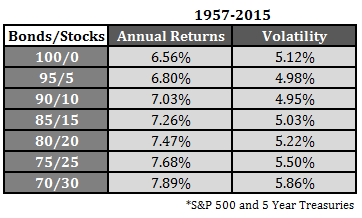

Let’s take a look at some historical returns to see why adding even a small allocation to stocks makes sense if you have a bond-heavy portfolio. These are the performance and volatility numbers for various stock and bond portfolio mixes going back to the late-1950s:

Ignore the absolute return numbers — bonds aren’t delivering 6.5% returns from here — and focus instead on the relative stats. A portfolio that’s made up of 100% bonds has roughly the same volatility as one that contains 20% in stocks, but the mix with 20% in stocks has annual returns that were almost 1% higher. Even going out to 30% in stocks doesn’t change the volatility profile that much.

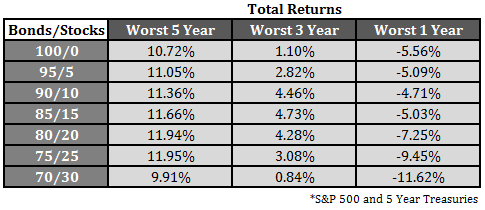

And since I’m not a huge fan of using volatility as a primary risk metric, here are the worst total returns for these same allocations on a one, three and five year basis:

Adding even a small amount of stocks to the mix actually improves the results during the worst case scenarios as stocks picked up the slack during periods of low returns in fixed income. Through the power of diversification and rebalancing (semi-annually in this example), a portfolio that many would consider higher risk from the additional equity exposure offers much better risk-adjusted returns on both volatility and losses, in most cases.

Again, investors can’t expect to earn these same kinds of returns in fixed income from current interest rate levels. But even if you are extremely risk-averse, adding even a small allocation to equities can actually improve your results without adding too much risk to your portfolio. And by ignoring the positive effects of diversification, you could actually be taking on more risk than you understand by investing in a single asset class.

Further Reading:

What’s the Worst 10 Year Return From a 50/50 Stock/Bond Portfolio?

is there ever a circumstance where you’d recommend CDs? (assuming low/zirp)

I actually think CDs are an under-rated form of interest rate protection. Many long-term CDs have better rates with a minor redemption penalty. That was if/when rates rise, the only int rt risk you have is that penalty. Plus FDIC insured up to $250k.

thanks ben. trying to get my parents to the beach. actually, they’re already there…maybe an island.

here’s a good article on what I was talking about: http://www.aarp.org/money/investing/info-2015/long-term-investment-savings.html

cool, thanks. i’ve never really done the homework on cds and comparing it to MMAs/high yield savings. as a young investor during the financial crisis, i think i was traumatized into avoiding cds altogether

“When” rates begin to rise, I imagine that the equity weighting will have to be subtantially higher than 20% to generate a satisfactory retirement portfolio return. Bond yields have been declining for 30 years, so all the previous studies and work done on bond/equity allocations will soon be irrelevant – if not already. IMO

True, this would be the rare case that the investor doesn’t really need to grow their portfolio. 2-3 decades in retirement means you’re going to need some growth, especially at today’s interest rate levels.

Yes, there are certainly risks in bonds. As Nick Murray would say “Bonds are a planned liquidation of purchasing power”.

Ben, why do people look at volatility. Isn’t it just standard deviaton? If you had a portfolio that went up 5%, then 25% then 5% then 50% in consecutive years you get a standard deviation of returns of 18.5% and would look volatile, but you have grown capital by 106% in 4 years. Surely, that’s what matters.

Very true. I’ve never considered volatility a risk, but that doesn’t mean you should completely ignore it. Volatility can turn into a risk if you react to it the wrong way. That’s why it’s so important to understand how you’ll react to it when it inevitably hits.

[…] Move to the beach and live off the interest? – AWOCS […]

[…] Transfer to the seashore and reside off the curiosity? – AWOCS […]

In the long run equities protect Your portfolio from inflation too.

Thanks for this article. I had a recent discussion with someone who needed to prioritize principal protection over return and was 100% bond funds, but also wanted a 5% annual return. This got me interested in this same topic. For some reason, the 15/85 split seemed to backtest well with a solid return and minimal drawdowns – better than going 100% bonds – especially if the 15% is split among US stocks, REITs, and EM – in which case the worst drawdown over the past 30 years was less than 3%. Might be different in the future, as Neil mentions below, but given that kind of result, it seems like a total bond portfolio should be a specialized and rare allocation.

That’s about what I found as well. I think many people would find these results surprising. Like most things in the markets, it’s counterinuitive.