I received a number of questions about this headline and story from Bloomberg yesterday:

This stuff scares people because it’s coming from an intelligent investor who made a name for himself during one of the biggest market crashes of all-time.

Sometimes even the best investors are too smart for their own good when it comes to understanding the simpler parts of the investing world. Here’s legendary hedge fund investor Seth Klarman’s take on index funds:

I believe that indexing will turn out to be just another Wall Street fad. When it passes, the prices of securities included in popular indexes will almost certainly decline relative to those that have been excluded. More significantly, as Barron’s has pointed out, “A self-reinforcing feedback loop has been created, where the success of indexing has bolstered the performance of the index itself, which, in turn promotes more indexing.” When the market trend reverses, matching the market will not seem so attractive, the selling will then adversely affect the performance of the indexers and further exacerbate the rush for the exits.

This too sounds scary. The problem is Klarman wrote this in his book, Margin of Safety, published in 1991.1

I get questions about the potential for a passive bubble on a regular basis so I figured it was time to put all my thoughts on the topic in one place.

Here goes.

Indexing is an odd risk to worry about. It’s bizarre that some people think it’s a bad thing investors are shifting money into funds that:

- save them money in fees

- are more tax-efficient

- have lower turnover and trading costs

- beat the majority of actively managed funds over the long-term

- are simpler and easier to understand than most investment strategies

It’s also bizarre to blame a bubble on the idea that more investors are actively avoiding the search for alpha by thinking and acting for the long-term. It’s like worrying about a trend where everyone decides to eat better, thus hurting sales at McDonald’s.

Index funds are nothing special.

But wouldn’t it be more worrisome if investors were piling into funds with high fees that are tax inefficient that also trade a lot and underperform simple market averages over time?2

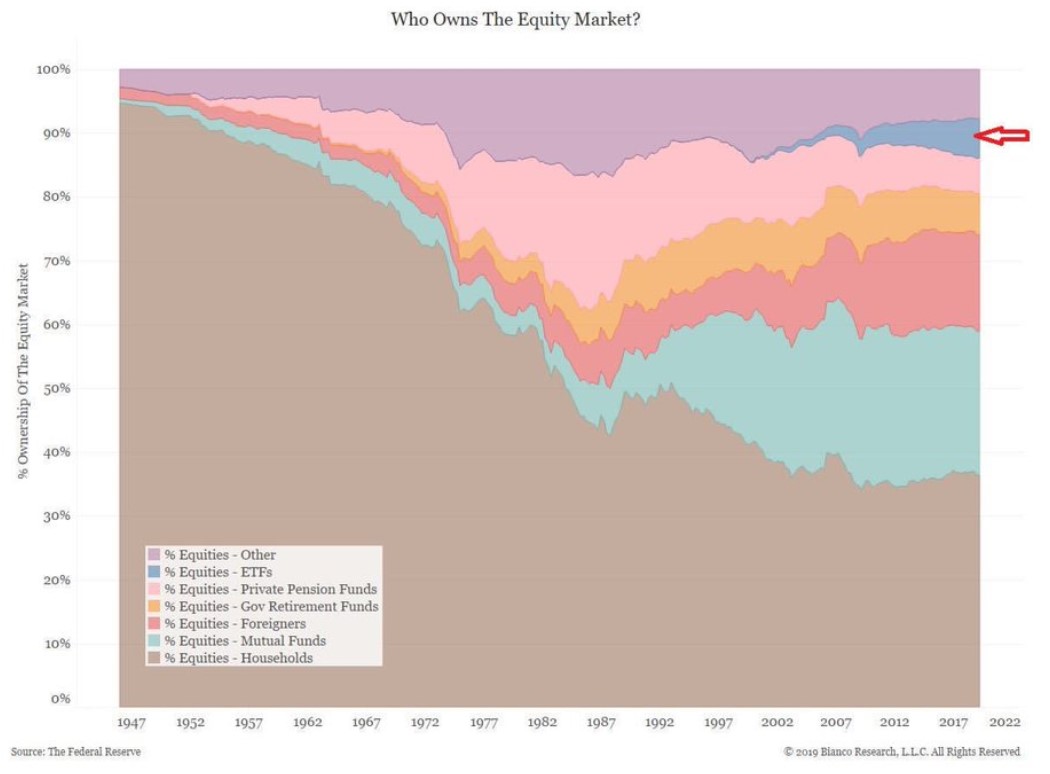

The tail is not wagging the dog. The fund world of mutual funds and ETFs is all most investors know these days but ownership of the stock market goes far beyond this world (h/t Nate Geraci):

Here’s the breakdown from John Bogle’s final book:

Yes, U.S. index funds have grown to huge size, with their holdings of U.S. stocks doubling from 3.3% of their total market value in 2002, to 6.8% in 2009, and then doubling again to an estimated 14% in 2018. Other mutual funds now hold an estimated 20% of corporate shares, bringing the mutual fund total to almost 35%, the nation’s most dominant single holder of common stocks.

So index funds hold less than 15% of shares in public companies. And according to former Vanguard CEO Bill McNabb, indexing in stocks and bonds globally represents less than 5% of global assets.

Why aren’t people more worried active managers are going to lead to a crash someday?

Benchmark huggers have always been around. Vanguard and iShares have experienced massive growth in the past 10-20 years, seeing trillions of dollars of inflows. But this doesn’t mean indexing is new. It’s just in a cheaper wrapper now.

Professional money managers have been closely tracking their benchmarks for decades now. That’s because those indexes are their benchmarks. Very few actively managed funds deviate much from those benchmarks because being different eventually leads to underperformance, which can lead these managers to get fired.

Career risk may be one of the greatest inefficiencies people never talk about but it’s there. And because career risk has always existed, closet indexing has been around for some time.

Plus there’s the fact that pensions and other large institutional investors have been creating their own index funds in-house using separately managed funds for years. We’re just seeing a shift from closet indexing to ETFs and other index funds en masse now that investors have wisened up.

Isn’t it a good thing investors are shifting away from expensive closet index funds?

Active funds literally own the market. When you buy an index fund of the total stock market, you are literally buying the stock market in proportion to the shares held by all active investors. If you sum up the collective holdings of active managers, what you basically get is a market-cap-weighted index. Index fund investors are simply buying what the active investors have laid out for them.

Plus we have to remember that not every cent flowing into index funds is going directly to the S&P 500 or a total market fund. Most of the money is going there but there are also index funds for small caps, mid caps, value, growth, sectors, themes, and everything in-between.

Many of the worries about indexing really boil down to career risk in the asset management space. By taking themselves out of the game and buying index funds, there are now fewer suckers at the poker table for the pros to take advantage of.

Isn’t it a good thing most small investors have decided they can’t compete with the professional active managers who trade with one another?

Price discovery is a cop-out. Active management will never completely go out of business because it’s far too lucrative and tempting for type-A personalities to prove themselves.

But people worry that as index funds continue to gain market share, the price discovery mechanism could become fragile. This is nonsense.

There’s plenty of price discovery going on in the markets. In fact, you could probably make the case there’s too much of it these days.

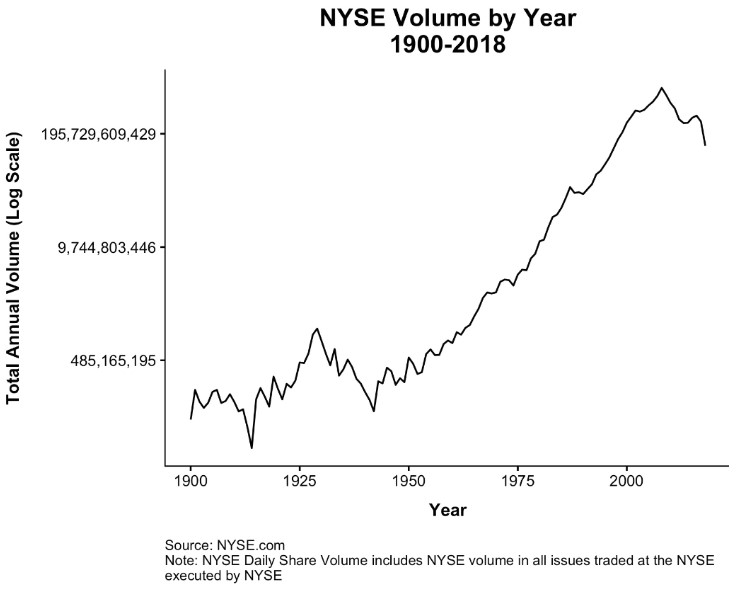

Fifty years ago or so, the entire New York Stock Exchange saw trading volume for all listed stocks of 3 million shares. Today, Apple has an average trading volume of roughly 26 million shares a day. Facebook turns over more than 16 million shares a day, on average.

Even the biggest stock market ETF (SPY) averages nearly 70 million trades a day.

Active managers will always set the prices, no matter how many there are.

Charley Ellis wrote in his book, The Index Revolution, that indexing accounts for less than 5% of trading, with the remaining 95% or so done by active investors. This will always be the case, no matter the amount of money flowing into index funds.

Here’s the NYSE volume by year:

I’m not complaining about the increase in volume. This is a good thing because it lowers trading costs and decreases bid/ask spreads.

But what’s a more worrisome trend for individual investors — people who have decided to trade less or people who have decided to trade more?

Yes, index funds are free-riders but so what? Cliff Asness wrote a wonderful piece for Bloomberg a few years ago about the idea of index investors being free riders:

The use of price signals by those who played no role in setting them may be capitalism’s most important feature. That most of us and most of our dollars don’t have to pick stocks, or to price air conditioners, is a great benefit and taking advantage of it makes us honest smart capitalists, not commissars.”

Yes, index investors are free riders, but this is the way most markets work. We don’t go to the grocery store to bid on prices of oranges against one another to set an equilibrium. The market does that for us.

Do you really think every investor in the market has the ability to accurately set prices?

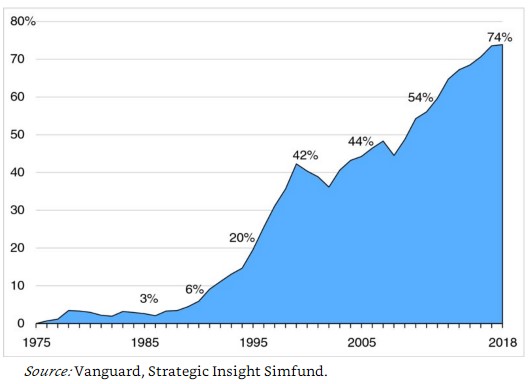

There’s room for both. It’s also worth pointing out the success of indexing doesn’t mean all active management is useless or bad. In fact, Vanguard itself still has a ton of money in active funds. Here’s the breakdown of assets in index funds for the firm (also from Bogle’s book):

The trend is easy to spot but the firm still has more than $1 trillion in actively managed funds. They just happen to manage their active funds using strategies that employ low turnover, long holding periods, and lower than average fees.

Won’t it be a net positive for the end investor that indexing will force the asset management industry to adapt?

Liquidity is not a huge problem for index funds. But, Ben, what if everyone rushes to the exits all at once? Index funds and ETFs are going to cause a massive crash!

When an index fund investor sells, they’re technically selling their holdings in direct proportion to their weighting in the index. So there is little market impact involved. Again, index fund investors are simply owning stocks in the proportion that all active investors own stocks.

Plus, index funds never lever up your holdings. They never receive a margin call. They don’t put 30% of your holdings in Valeant Pharmaceuticals. And no index fund has ever closed up shop to spend more time with their family.

There will always be investors that panic, regardless of the type of fund they’re invested in.

Why would index funds or ETFs be any different than any other fund type or security in that respect?

Humans matter more than fund structures. People love attaching a narrative to what transpires in the markets. Index funds have been the perfect scapegoat in a market that has gone up for 10 years and pretty much outperformed every other strategy.

This won’t last forever but the next time the market crashes will have more to do with investors than index funds.

Do you know what didn’t cause the Great Depression or Japan stock market crash or 1987 crash or 1973-74 bear market? Index funds.

Index funds also weren’t around for the South Sea bubble in the 1700s.

Do you know what did cause these bubbles and subsequent crashes? Human nature.

Could the stock market itself become a bubble yet again? Of course. There will always be bubbles.

Are index funds perfect? No. They give you all of the upside of the stock market but also all of the downside. And indexes can go nowhere for years on end just like individual stocks. They can become overpriced and underpriced. They own the good stocks and the bad stocks.

But that’s nothing new. That’s the stock market for you.

This passive bubble talk is silly. Wake me up when index funds control 90% of the stock market.

Further Reading:

Playing Devil’s Advocate on Index Funds

The Gradual Explosion of Index Funds

Could Index Funds Become Too Popular?

1See this similar warning from 1975 courtesy of Eric Balchunas.

2As my colleague Josh Brown recently pointed out, if anything active management is the bubble that’s slowly deflating, not an index bubble that’s inflating.