I received a huge response about my post from earlier this week where I showed that a 60/40 Vanguard portfolio beat the majority of college endowment funds over the previous 5 and 10 year periods. I’m always willing to see the other side of an argument, so I wanted to dig a little deeper into the biggest pushback I received which was some variation on this:

Sure, but what were the risk-adjusted returns? How much volatility did each set of returns have?

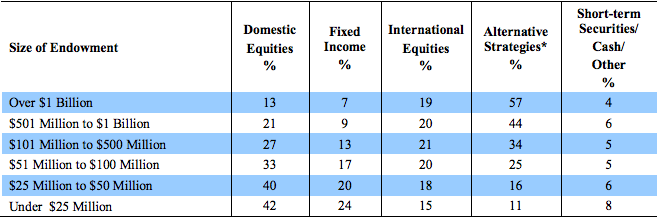

Take a look at the average asset allocations for these funds from the NACUBO study I referenced in the earlier piece:

The first thing that you should notice is how heavily these endowments rely on alternatives, such as private equity, hedge funds and real assets. The second thing would be how tiny their allocation is to traditional fixed income. One of the reasons for these allocations is the fact that most of these funds have a time horizon that basically goes on forever. It’s what we in the industry call a perpetuity. So these numbers show that my 60/40 comparison was probably far too conservative. I should have compared the numbers to an 80/20 or even 85/15 portfolio in some cases.

Regardless of the performance numbers, the time horizon of the majority of endowments shows that their ability to take risk is substantial with most of their money. This is aided by the fact that most bring in huge alumni donations that can help meet current spending needs. Therefore, why would they have the need to worry about short-term volatility and risk-adjusted returns? If anyone can stand to take on more volatility, it’s a fund that has an unlimited time horizon (understanding the fact that they still have to meet short-term spending needs, hence the allocations to cash and fixed income).

Now, ability to take risk and time horizon are just two of the many necessary inputs we use when figuring out risk tolerance. You also have to factor in your need and willingness to take risk. Because of the huge scare that was put into many of these funds during the financial crisis most no longer have the willingness to take as much risk. And that’s fine as long as they are still able to achieve their goals. There’s no reason to take more risk than you’re willing or need to stomach because that can lead to poor decisions when risk invariably flares up.

The problem with all of this talk about risk is that people in the investment industry assume that risk is easily quantifiable by calculating standard deviation or volatility. Here’s why this is a problem for the alt-heavy endowment portfolios:

- Private equity, venture capital and real asset holdings are valued on a quarterly basis. And these valuations are usually done by the fund companies themselves who hold the positions. There’s no way that these holdings give you a legitimate sense of actual portfolio volatility from an overall portfolio perspective. Quarterly marks don’t do justice to the potential valuation changes in these portfolios, especially when you consider that they are valued on a lag of up to 3-9 months in some cases. (Although not being able to view the daily changes may be a benefit from a behavioral perspective).

- Alternative funds tend to come with leverage, concentrated holdings, limited holding transparency, illiquidity and higher-than-average-fees. These risks may not be quantifiable like volatility, but they exist nonetheless. It can be hard to define risk when you’re not really sure what your actual fund holdings are and what kind of leverage is being applied to earn your returns.

- They say that you can’t eat risk-adjusted returns. Targeting lower volatility in hedge fund strategies tends to be partnered with lower returns, as so many investors have discovered in the past decade or so. Taking lower risk usually leads to lower returns.

- Following heavy losses in the 2007-2009 period many endowments realized they couldn’t handle volatility so they changed their strategy near the bottom by investing more in downside volatility protection. What many failed to realize is that market rallies tend to exhibit lower volatility, so many missed out on some of the best risk-adjusted returns ever in the stock and bond markets.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m a huge proponent of practicing prudent risk management. I just think that it’s ridiculous to try to narrow down risk to a single number or equation. It’s much more nuanced than that. Calculating volatility-based equations on past performance numbers is not risk management. Risk management is an ongoing process, not a number. There are many risks out there that you can’t boil down to a math problem.

According to the Internet (so it has to be true), Einstein once said, “Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted.”

Further Reading:

Bogle vs. Goliath

Couldn’t agree more – “There’s no way that these holdings give you a legitimate sense of actual portfolio volatility from an overall portfolio perspective.”

Easy for people to only look at return numbers when figuring these things out without putting them into the correct context.

Excellent. This takes the theory into the real world, particularly one run my imperfect investment committees.

Thank you. And I do have sympathy for most ICs because they hear the same thing from every consultant they talk to. No one is really giving it to them straight.

Do IC’s have consultants to help them select the right consultant to assist them in selecting the appropriate investment managers? Haha.

Who watchers the watchers, right?

Who watchers the watchers, right?

#fail

William Goldman, amplified by Andy Grove:”No one knows anything.”

A very good starting point for investors.

“Alternative funds tend to come with leverage, concentrated holdings, limited holding transparency, illiquidity and higher-than-average-fees. These risks may not be quantifiable like volatility, but they exist nonetheless. It can be hard to define risk when you’re not really sure what your actual fund holdings are and what kind of leverage is being applied to earn your returns.”

You can try using the 2nd and 3rd derivatives (skew & kurtosis) to quantify draw down risk for these funds?

At last, main street is catching on… volatility is a very poor measure of the risk of a strategy… yes, that includes volatility of past performance, backtest, Sharpe, drawdown, etc. If I told you glass is stronger than a rubber band because it bends less when pushed, would you believe me?