A reader asks:

I’ve heard you say quite a few times that “trees don’t grow to the sky”, and you’re usually talking a particular company or Bitcoin or maybe ARK, etc.

But could the same be true for the stock market in general, i.e., does it hit a point where it simply can’t grow anymore. After all, money and dollar are scarce and limited. If everyone hypothetically invests, we can’t all become millionaires, right?

Is there a point at which the stock market simply can’t keep going higher?

The idea that trees don’t grow to the sky is generally directed at outperformance.

No strategy can outperform always and forever. If such a strategy existed so much money would pile into it that it would stop working. Size is the enemy of outperformance after all.

But does this apply to the stock market in general?

Well the stock market itself can only outperform those investors who buy and sell at the wrong time. The market is simply the collective actions and decisions of everyone investing in stocks.

If we all woke up one day and decided we were not going to try to improve ourselves anymore, there will be no more innovation and we’re just happy where we are then, sure, the stock market would likely stop going up. If the economy stops growing and people or corporations stop producing profits, the stock market will stop being a compounding machine.

I don’t necessarily think that’s going to happen because moving forward is in our DNA. It’s what sets us apart as a species.

Over the past century or so we’ve endured world wars, pandemics, recessions, financial panics and a lot of other bad stuff. Yet the stock market is still up something like 10% per year in that time.

I do, however, think that it makes sense to temper your expectations for future stock market returns. I’m not sure that 10% is going to happen going forward for a few reasons.

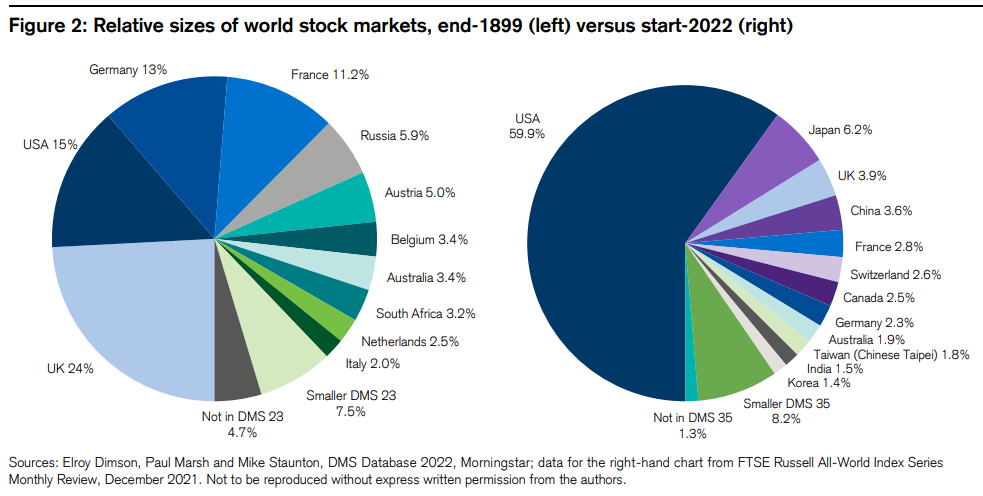

This is one of my favorite charts courtesy of the Credit Suisse Yearbook:

The U.S. stock market has grown from 15% of world equity markets to 60% since the onset of the 20th century. We’re basically eating the rest of the world Pac-Man style.

It doesn’t seem likely this can continue for another century.

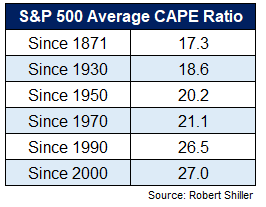

The fact that average valuations have increased should mean lower returns going forward as well. You can see the averages have been rising for some time now:

This makes sense when you consider how much riskier it was to invest in the stock market in the early 20th century.

During World War I, the stock market closed for 6 months because liquidity all but dried up when everyone went to war.

The Federal Reserve was only created as the lender of last resort a year before the Great War started. By the time the Great Depression rolled around they still had no idea what they were doing and only made things worse.

It’s part of the reason the stock market fell something like 85% in that crash.

Could that happen again?

I’m not sure the government or the Fed would allow it. If we take that kind of risk out of the equation, you would expect risk premiums to compress.

Back then valuations had to be lower to entice investors to invest in stocks.

Obviously, this doesn’t mean the risk of a market crash has been eliminated. Volatility in the stock market is impossible to get rid of — just look at the past 3 years. It’s just that the Armageddon scenario is probably off the table unless we have an actual Armageddon.

But even if I’m right about future returns being lower, that doesn’t necessarily mean investors are going to be worse off than they were in the past.

The only thing that matters to the end investor is returns net of all fees, taxes and transaction costs. All of those things are much lower now than they were back in the day.

It used to cost anywhere from 1-3% of you your purchase price in commissions to trade a stock. Then came May Day in 1975 which is when brokerages were finally allowed to set their own prices for trades.1 The discount brokerage was born and now those costs have been completely wiped out as it doesn’t cost anything to trade stocks with most brokers anymore.

People used to trade stocks using fractions instead of decimal points. Now they use computers instead of chain-smoking guys wearing funny coats on an exchange who spent all day screaming at one another. Bid-ask spreads have also collapsed.

Index funds didn’t exist until the 1970s. You used to have to pay an upfront fee called a load to buy a mutual fund. Even the first index fund from Vanguard contained an 8% charge on your purchase price.

The 401k was only created in 1978. Roth IRAs have only been around since 1997. The first ETF was also in the 1990s.

It’s never been easier to invest in the stock market at a low cost using tax-deferred retirement accounts.

So while investors may earn lower gross returns going forward, the net returns could be the same or even higher than in the past since so many frictions have been eradicated.

The biggest tax on investors today comes in the form of bad behavior.

We discussed this question on the latest Portfolio Rescue:

Jonathan Novy joined me this week to answer questions about pensions, whole life insurance, annuities, stock-bond allocations, 529 plans and more.

Further Reading:

Trading Costs & the New Market Averages

1From 1900-1975 the average CAPE ratio was a little less than 15x. Since 1976 it’s close to 22x.