I read plenty of stories in the financial media about the coming retirement crisis, but I see far fewer people willing to offer legitimate solutions to the problem of under-saving by the majority of Americans.

Legendary author and investor Charley Ellis put out a book at the end of last year — Falling Short: The Coming Retirement Crisis and What to Do About It — that outlines the issues many are going to face when it comes to keeping up their standard of living in retirement. But the book also offers some solutions for those dealing with this problem.

Ellis laid out the four most important factors that help determine whether or not you’ll have a large enough nest egg to cover your living expenses during retirement:

1. Earnings. The higher our earnings, the smaller the proportion provided by Social Security and the higher our own required saving rate.

2. Age when saving starts. The earlier we start saving, the lower the required rate of saving needed for any given retirement age.

3. Age at retirement. The later we retire, the lower our required saving rate.

4. Rate of return. The higher the rate of return on our investments, the lower our required saving rate.

We have varying degrees of control over each of these. People have the power to earn more money by enhancing their career prospects. The age in which you retire could be affected by poor health or employment issues that force people to retire earlier than they would like, so this one is a toss-up. And no one has any control over the financial market returns that the markets offer (although people do control how much of those returns they earn).

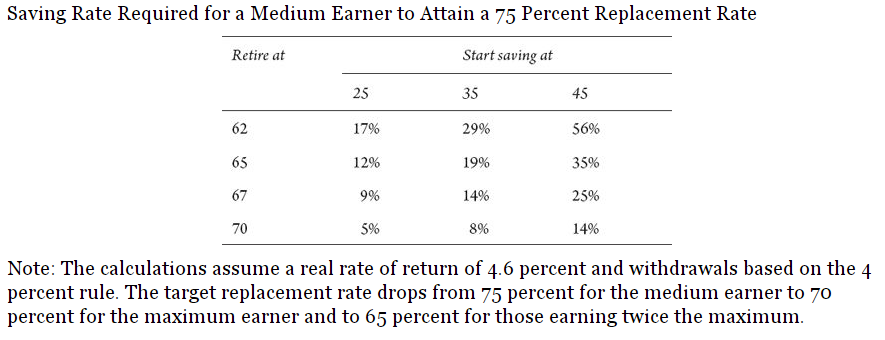

Out of the four, the second option — the age when saving starts — is the one people have the most control over. Ellis goes on to outline a study that shows just how important this one can be over time as you can see the different savings rates required depending on the start and end dates:

The conclusion of the study sums this up nicely (emphasis mine):

Starting to save at age 25, rather than age 45, cuts the required annual saving rate by about two-thirds. And delaying retirement from age 62 to age 70 reduces the required annual saving rate by more than two-thirds— from 17 percent to 5 percent (or 29 percent to 8 percent for those who start at 35, or 56 percent to 14 percent for those who start at 45.) Taken together, starting at 25 and working to 70— compared to starting at 45 and retiring at 62— reduces the required annual saving rate by a factor of 10!

This simple example shows how the power of compound interest can provide the majority of the heavy lifting for you if you’re able to use it to your advantage. William Bernstein shared a similar stat in his book, The Investor’s Manifesto (again emphasis mine):

Each dollar you do not save at 25 will mean two inflation-adjusted dollars that you will need to save if you start at age 35, four if you begin at 45, and eight if you start at 55. Since a 25-year-old should be saving at least 10% of his or her salary, this means that a 45-year-old will need to save nearly half of his or her salary.

You could play around with the rates of return and savings rates in these simulations, but the conclusion is clear that starting to save money at an early age is one of the best things you can do to build wealth. It allows you to save less money overall and lowers the burden on your future self so you aren’t forced to scramble to play catch-up later in life.

One of the best ways to get useful financial advice is to ask those who are older than you what they wish they would have done at your age. A recent study from Wells Fargo did just that. Three out of four survey respondents 40 years of age or older said their biggest financial regret is that they didn’t start saving money earlier. Yet of the non-retirees in that group, more than half said they are still waiting to ramp up their current savings rate to make up for the shortfall. They know where they went wrong, but they still can’t bring themselves to correct the mistake.

As with most financial habits, knowing what you need to do is the easy part. Following through with it is where most people run into trouble.

Sources:

Falling Short: The Coming Retirement Crisis and What to Do About It

The Investor’s Manifesto

Further Reading:

When Saving Trumps Investing

A Simple Way to Reduce Portfolio Risk

Hey Ben,

Nice summary. One aspect of “retirement” that is very rarely addressed is the fixed cost/expense side of the ledger. It has been my experience with clients and spending many, many hours with retirees that many of these folks “chase nickles.” Many have one or two houses that are too big and rarely use. Some still have mortgages and many retirees still dump money into improvements as if they have 25 more years to recoup their investment. And that is just the houses. Many pinch pennies all day long and than hop in their 35-50K brand new vehicles or have a boat in dock that they use 3 times a year. So many retirees are slaves to the non-income or cash flow negative asset side of their balance sheet that is mind boggling.

Great points. I think retiring without any mortgage debt should be right up there in terms of retirement goals. It just opens up so many different options for people if they want to downsize or not. I’m a big fan of paying attention to the really big purchases in your life as well if you’re going to make any financial progress. I say spend your money however you want as long as you have a solid savings plan in place. As you point out many spend first and try to save later which doesn’t work.

I can imagine conditions under which I’d follow the advice to pay off the house early, but I guess my wife and I are ok with a bit more risk. Wouldn’t be a tragedy sell this house, but in the meantime we have a 30 yr 3.5% fixed refi that will go at least 10 yrs into retirement. The cash flow that could go to early payoff goes instead into a business and investments, and it appears both will return well in excess of the 3.5% interest cost.

But then, I have a hard time understanding how most people expect to retire. When I look at savings rates for our age, we’re in the top 1 or 2% of savings relative to income, and aiming for 100% income replacement (we want to travel and my wife is picky about accommodations!) – factoring in SS at 75% of promised benefits, it’s a far from sure thing to make that last 40 years without potential lifestyle adjustments. That means the other 98% must be planning to make such adjustments? (It’s an interesting calculation though – there’s a break point at which your assets just keep growing, and it’s a relatively small bump from what you need for 40 years).

Yup, especially with lower interest rates this decision can become a little trickier. Many are actually going into more debt and carrying mortgage debt into retirement with little savings. It’s going to be difficult for many to keep up their current lifestyle.

I agree. There is a lot of blood that can be squeezed out of the US turnip still before there is a real crisis.

Yup. It’s just that many have to lower their expectations.

Of interest is the decades old mantra that one needs a million dollars to retire “comfortably”. I did some (Canadian) research and found that <1% of the population has the coveted million dollars (the average retiree has a nest egg of ~$300,000). Yet people are still retired and retiring and will continue to do so — regardless of savings rate. If the actuarial trends play out, upon full Boomer generation retirement, millionaire status will reach a whopping 2% of the population, and then plummet back down to 1% once the last Boomer has shuffled off this ridiculous coil (all Canadian figures).

It may be that the million dollar benchmark was set by the materialistic Boomer era and perhaps it is only they who will be facing difficulties meeting that mark (and/or supporting their retirement dreams); something which has not effected their parents (who were conditioned to live frugally) or their children (who have clued into the folly of trying to chase so much stuff). Different mindset, different outcome.

Speaking of which, there is now a growing trend amongst the Millennial/Gen Y set to consciously purse a vagabond-hobo-riding-the-rails lifestyle, devoid of any fixed address and heavy possessions (read lots of expenses). Hoboism initially caught traction during the Great Depression when broke men were forced by necessity to seek jobs in other parts of the country. Today it appears to be all about not getting caught up in long-term financial despair they see all around them (lack of work ethic and purpose might have a heavy hand in the mix as well, but I'll just stick to the money related stuff).

Even Canada's recent budget chopped the projected long-term returns of retirement savings accounts in half from 6% down to 3% (used to calculate age-forced withdrawal rates). Not too rosy an outlook.

In the end, save and invest early, figure out your direction as you go, know thyself* and make peace with reality because few of us end up exactly where we plan on going!

(*if you really love spending and having all the stuff then be prepared to do what it takes to ensure you can continue to spend and have stuff after you stop working.)

Well said. I jsut told someone recently if we really had a retirement crisis there would be bread lines full of old people. People adapt. One of the biggest things is having your mortgage paid off. That offers a ton of advantages. Life style inflation, as you mention, is another big one. But I agree you can’t plan these things out to the second decimal point — you have to be flexible and update your plan as life happens.

[…] The four pillars of retirement savings. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

[…] Doug Short for full story and charts). On the other hand, prices are a buck lower than a year ago (Calculated Risk for charts and […]

[…] Doug Short for full story and charts). On the other hand, prices are a buck lower than a year ago (Calculated Risk for charts and […]

[…] Further Reading: The Four Pillars of Retirement Savings […]

[…] Further Reading: The Four Pillars of Retirement Savings […]